In the twisted corridors of cinema history, there lurks a fever dream that refuses to fade into obscurity. Robert Wiene’s “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” (1920) crawls through the mind like a shadow that’s learned to dance, a macabre waltz of madness and manipulation that birthed horror cinema as we know it. This isn’t just a movie – it’s a descent into the fractured psyche of post-World War I Germany, where reality bends like the film’s impossible architecture, and truth becomes as elusive as smoke in a hall of mirrors.

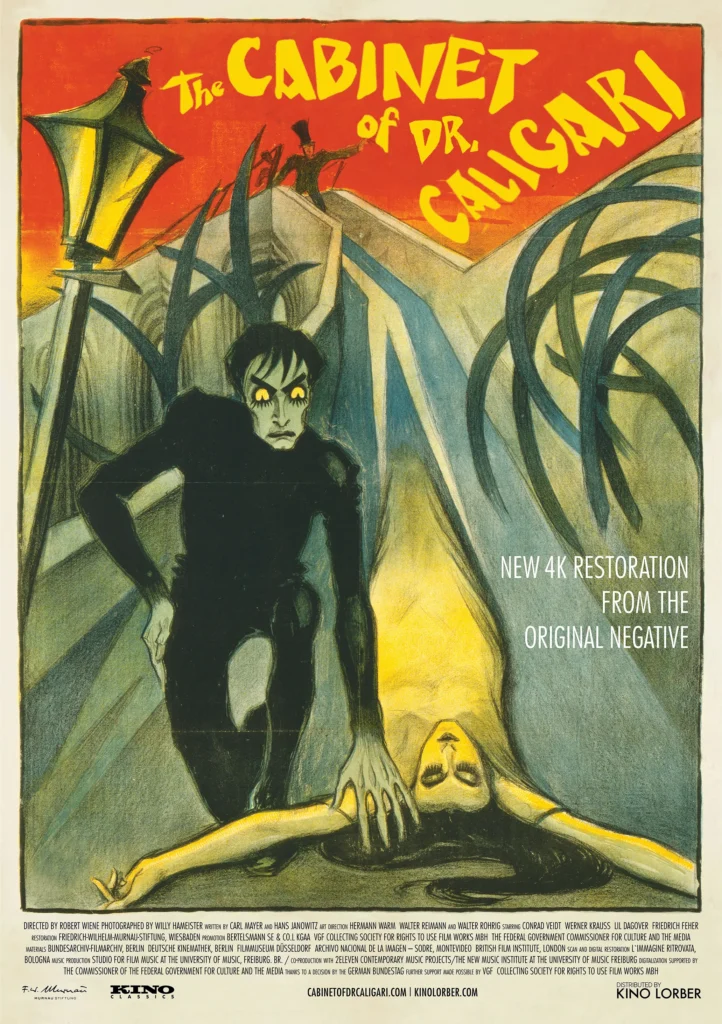

From its first frame, Caligari grabs you by the throat with its grotesque beauty. The world it creates isn’t our own – it’s a nightmare playground where buildings lean like drunk giants, shadows fall in impossible patterns, and every corner seems to hide a secret that’s better left unexplored. The set designers – Hermann Warm, Walter Reimann, and Walter Röhrig – didn’t just build backgrounds; they constructed a visual manifestation of mental collapse, painting darkness directly onto the sets with a madman’s precision. Each frame feels like a painting torn from a paranoid’s gallery, where perspective is merely a suggestion and reality is negotiable.

I remember my first encounter with this film in a dimly lit college screening room. The silence of the audience was absolute, broken only by collective gasps as Cesare emerged from his cabinet for the first time. Even now, decades later, that moment retains its power to shock and mesmerize. The film seems to reach through time with skeletal fingers, grabbing modern viewers by the throat with the same force it exerted in 1920.

The story unfolds like a puzzle box designed by a lunatic. Francis, our supposedly reliable narrator, spins a tale of murder and manipulation centered around the mysterious Dr. Caligari and his prophetic sleepwalker, Cesare. Werner Krauss embodies Caligari with the intensity of a cobra waiting to strike, his performance a masterclass in contained malevolence. His movements suggest a man possessed by an idea so terrible it’s transformed him into something barely human. In his eyes, you can see the birth of every mad scientist who would follow in his twisted footsteps.

But it’s Conrad Veidt as Cesare who haunts your dreams long after the credits roll. His otherworldly movements, somewhere between dance and death throes, created a template for horror performance that echoes through the decades. Watching him emerge from his cabinet-coffin for the first time, I felt my breath catch – here was death itself taking human form, every gesture calculated to remind us that we’re watching something that shouldn’t exist. You can see his influence everywhere: in Karloff’s Frankenstein, in Max Schreck’s Nosferatu, in Heath Ledger’s Joker. Veidt didn’t just play a character; he created an archetype that horror cinema would spend the next century trying to recapture.

The genius of Caligari lies not just in its surface-level chills, but in its layers of meaning that peel away like dead skin. Created in the aftermath of World War I, the film emerges from a Germany traumatized by defeat and teetering on the edge of chaos. The script, penned by Hans Janowitz and Carl Mayer – both scarred by their wartime experiences – burns with a distrust of authority that feels prophetic. Janowitz served as an officer and came back bitter; Mayer faked madness to avoid service and endured horrific psychiatric examinations. Their personal traumas bleed into every frame of the film, transforming their experiences into a universal nightmare about power and control.

What strikes me most about revisiting Caligari in our current political climate is its prescience about the nature of authoritarianism. Dr. Caligari, with his ability to bend others to his will, emerges as a terrifying preview of the authoritarian horrors that would soon engulf Europe. The film’s exploration of power and manipulation reads like a warning letter from the past, sealed with tears and blood. When I watch Caligari manipulate Cesare, I can’t help but see a chilling prophecy of how future dictators would manipulate entire populations. The film seems to whisper across time: “Watch carefully – this is how freedom dies, not with a bang but with a hypnotic suggestion.”

The German Expressionist movement that Caligari helped launch wasn’t just an artistic style – it was a primal scream captured on celluloid. Every frame feels like it was torn from a paranoid’s sketchbook, each scene composed like a nightmare’s family portrait. The film creates tension not through quick cuts or jump scares, but through the sustained discomfort of existing in a world where nothing is trustworthy, not even the ground beneath your feet. The jagged sets and painted shadows aren’t just artistic choices – they’re manifestations of a society’s collective mental breakdown.

I’m particularly haunted by the film’s use of space and architecture. The twisted streets of Holstenwall, where much of the action takes place, feel less like a real town and more like the maze-like corridors of a troubled mind. Buildings don’t just lean – they loom, they threaten, they bear down on characters like the weight of history itself. Every angle seems calculated to maximize psychological discomfort, creating a world that reflects the inner turmoil of its inhabitants.

What truly elevates Caligari beyond mere historical curiosity is its revolutionary approach to narrative structure. The film’s infamous twist ending – revealing Francis as an unreliable narrator confined to an asylum – doesn’t just pull the rug out from under the audience; it questions the very nature of truth and perception. Every distorted angle and impossible shadow suddenly takes on new meaning. Were we watching a story of madness, or the madness of storytelling itself? The twist was reportedly forced upon the writers against their will, yet it transforms the film into something even more profound – a meditation on the nature of reality itself.

Watch how the film plays with perspective in the scene where Cesare kidnaps Jane. The twisted streets become a maze of shadows and angles, every frame composed to maximize disorientation. The sequence haunts me because it suggests that even space and time are subject to manipulation. The way Cesare glides through these impossible streets with his victim feels less like a chase and more like a descent into the subconscious, where physical laws break down and nightmare logic reigns supreme.

The film’s influence bleeds into every corner of horror cinema. Its DNA can be found in the gothic architecture of Universal horror, the psychological twists of film noir, and the reality-bending narratives of modern psychological thrillers. When I watch Tim Burton’s films, I see Caligari’s distorted worldview filtered through a modern lens. When I experience the reality-questioning narratives of films like “Shutter Island” or “Inception,” I hear echoes of Francis’s unreliable narration.

What’s remarkable is how modern Caligari feels in its themes. Its exploration of gaslighting and institutional power could be ripped from today’s headlines. The way it questions the reliability of narrative and the nature of truth feels particularly relevant in our “post-truth” era. When Francis tells his story, we’re forced to question not just his sanity, but our own ability to distinguish reality from delusion. In an age of “alternative facts” and competing narratives, Caligari’s central question – “Who can we trust to tell us what’s real?” – has never felt more urgent.

The film’s technical achievements, revolutionary for 1920, retain their power to unsettle. The stark contrast between light and shadow, achieved through painted light effects on the sets themselves, creates a world of pure expression where emotion shapes reality. The makeup design, particularly on Cesare, transforms human faces into masks that reveal rather than conceal the darkness within. Even the intertitles, with their artistic lettering and dramatic declarations, contribute to the overall sense of a world slightly out of joint.

One aspect that particularly fascinates me is the film’s treatment of Jane, played with haunting vulnerability by Lil Dagover. Her character exists in a liminal space between victim and participant, her somnambulistic state in the frame story suggesting that she, like Cesare, might be another puppet in someone else’s grand design. The way the camera lingers on her trance-like states creates an unsettling parallel between her condition and the audience’s own mesmerized state while watching the film.

But perhaps most disturbing is the film’s subtle suggestion that madness might be the only sane response to an insane world. In the wake of a war that had shattered all notions of civilized behavior, who could claim with certainty where sanity ended and madness began? The asylum’s walls become less a barrier between reason and chaos than a mirror reflecting society’s own delusions. Every time I watch the film, I find myself wondering: If Francis is truly mad, what does that say about the world that drove him to madness?

The film cost a mere $12,371 to make – a pittance even by 1920 standards – yet its influence on cinema is incalculable. Its commercial failure at the time ($4,713 at the box office) stands in stark contrast to its artistic triumph. Sometimes, it seems, nightmares are too profound for their own time. But like all great art, Caligari waited patiently for the world to catch up to its vision.

For modern viewers, watching Caligari is like discovering the first nightmare ever committed to film – a primal scream of artistic expression that echoes through the decades. It’s a reminder that true horror doesn’t come from monsters or violence, but from the realization that reality itself might be nothing more than a story we tell ourselves to keep the darkness at bay.

In the end, “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” isn’t just a movie – it’s a warning about the fragility of truth, a meditation on the nature of authority, and a reminder that sometimes the most terrifying stories are the ones we tell ourselves. As you watch Francis tell his tale in that garden, remember: you’re not just watching a horror movie, you’re witnessing the birth of cinematic nightmare, a dream from which film has never fully awakened. And perhaps, like Francis, we’re all just unreliable narrators, telling stories to make sense of a world that defies understanding.