In the fog-shrouded realm of Universal’s monster pantheon, The Wolf Man 1941 prowls with a savage grace that sets it apart from its gothic brethren. This isn’t just another creature feature – it’s a blood-soaked ballad of inevitability, a nightmare where the beast within breaks free beneath autumn moons and wolfbane blooms.

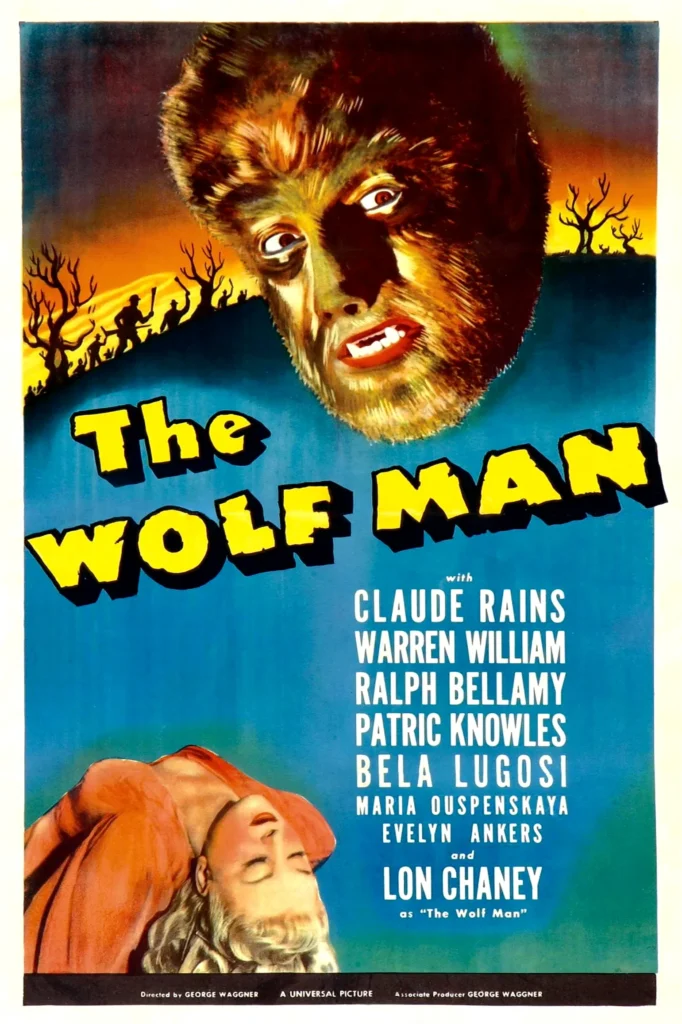

The year was 1941. While war drums echoed across Europe, Universal Pictures unleashed its own dark prophecy of transformation and inner turmoil. Through the cursed eyes of Larry Talbot (Lon Chaney Jr.), we witness a man’s desperate spiral into biological horror – not through science gone mad like Jekyll’s potion or Frankenstein’s lightning, but through the primal forces of myth and moonlight.

Chaney Jr. brings raw vulnerability to Larry Talbot that still cuts deep 80+ years later. Before the fur and fangs emerge, we see a man trying to reconnect with his roots, fumbling through awkward telescope-enabled flirtations and attempting to bridge an 18-year gap with his father. There’s something devastatingly human in Chaney’s performance – the way his eyes betray mounting terror as the curse takes hold, how his broad shoulders seem to carry the weight of ancient prophecies he never asked to inherit.

The film’s atmosphere is a masterwork of suggestion and shadow. Universal’s backlot transforms into a fog-drenched Welsh hamlet where ancient superstitions still hold sway. The trees twist like arthritic fingers against silver-clouds, while Jack Pierce’s groundbreaking makeup effects ensure that when our protagonist finally surrenders to his lupine curse, it’s a transformation that brands itself into the viewer’s psyche. Those who mock the “dated” effects miss the point entirely – there’s primal power in watching Talbot’s feet curl into bestial claws, in seeing humanity literally peeled away one frame at a time.

Claude Rains brings aristocratic gravity as Sir John Talbot, creating a father-son dynamic that elevates this beyond mere monster movie territory. Their scenes crackle with unspoken pain – a chasm of lost years and mounting dread as Sir John watches his prodigal son descend into what he believes is madness. When he finally faces the truth, it’s with the same silver-headed cane that will end his son’s torment. The tragedy reaches Greek proportions.

Maria Ouspenskaya’s Maleva emerges as the film’s dark prophet, her weathered face and hypnotic cadence lending weight to every word. When she intones “The way you walked was thorny, through no fault of your own,” it feels less like dialogue and more like an incantation, a funeral dirge for Larry’s humanity. Her presence connects the film to something older than cinema, to firelit tales of transformation and fate’s cruel hand.

The screenplay by Curt Siodmak (who crafted the now-iconic werewolf poem from whole cloth) works on multiple levels. On the surface, it’s a tight thriller about a curse and its consequences. Dig deeper, and you’ll find a meditation on the beast that lurks in every human heart. Larry’s transformations can be read as metaphors for everything from mental illness to repressed rage, from teenage growing pains to the savagery of war that was engulfing the world as the film premiered.

What strikes me most about The Wolf Man is how it refuses easy moral categorization. Larry isn’t a mad scientist playing God or a criminal paying for his sins – he’s an ordinary man caught in an extraordinary curse. His attempts to warn others, to protect those he might harm, make him deeply sympathetic even as his bestial alter-ego rends and tears through the fog-bound night. The film suggests that monsters aren’t always born from evil – sometimes fate alone bares its fangs.

The technical artistry deserves special mention. Joseph Valentine’s cinematography turns every moonlit forest into a landscape of nightmare logic. Shadows don’t just darken the frame – they pulse with menace. The transformation sequences, achieved through dissolves and painstaking makeup changes, carry a documentary-like weight. We’re watching a man become a beast in real-time, each frame a death knell for his humanity.

The film’s pacing might seem brisk by modern standards, but this works in its favor. There’s no fat here, no unnecessary subplots or comic relief to break the mounting tension. From the moment Larry returns home to the final, tragic confrontation with his father, we’re locked into a death spiral with our doomed protagonist. The brevity makes it feel like a fevered nightmare, one that’s all the more powerful for its concentrated punch.

Looking at The Wolf Man through modern eyes, what stands out is its emotional maturity. While later werewolf films would amp up the gore and sexuality of the myth, this version stays focused on the human tragedy. Larry’s curse isn’t just about growing fur and fangs – it’s about losing control, about watching helplessly as you become something that threatens everything and everyone you love. In our era of anxiety and transformation, this resonates more powerfully than ever.

The film’s influence on pop culture can’t be overstated. Every werewolf transformation sequence, every silver bullet, every full moon freakout owes a debt to this primal howl of a movie. But beyond establishing genre tropes, The Wolf Man showed how monster movies could be vehicles for exploring the human condition. When Larry peers into mirrors, desperately checking for signs of the change, we’re watching a man confronting his own potential for violence and destruction. It’s a moment that echoes through decades of horror cinema.

What makes The Wolf Man truly special is how it maintains its power even after countless viewings. The shadows still creep, Maleva’s warnings still chill, and Larry’s fate still breaks hearts. It’s a reminder that the best horror films aren’t about the monster’s appearance – they’re about the terrible waiting, the dread of knowing that darkness is coming and being powerless to stop it.

In our modern age of CGI transformation sequences and gore-filled horror, The Wolf Man stands as a testament to the power of suggestion and psychological terror. It’s a film that understands our deepest fears aren’t about what lurks in the shadows – they’re about becoming the thing that lurks in the shadows. Larry Talbot’s tragedy is universal because we all fear losing control, losing our humanity, becoming something that threatens those we love.

This profound empathy for the monster marks a crucial evolution in horror cinema. While contemporary critics in 1941 praised the film’s technical achievements, they often missed its deeper resonance. The New York Times dismissed it as merely “another of Universal’s efforts to maintain the horror market,” but time has revealed layers of meaning that transcend simple genre classification. Modern scholars like David J. Skal have noted how the film’s themes of transformation and loss of control spoke directly to a world being torn apart by war.

The film’s treatment of its female characters deserves particular attention. While Evelyn Ankers’ Gwen Conliffe might seem like a typical romantic interest at first glance, there’s something more complex at play. Her position between Larry and Frank Andrews creates not just a love triangle, but a metaphor for civilization versus savagery. Her character represents the societal norms Larry struggles to maintain even as his cursed nature pulls him toward darkness. It’s a nuanced portrayal that, while limited by the era’s conventions, suggests deeper themes about gender roles and social constraints.

What strikes me most personally about revisiting The Wolf Man is how it speaks to our contemporary struggles with mental health and identity. In an era where we’re increasingly aware of the shadows we all carry, Larry’s desperate attempts to warn others of his condition feel less like supernatural horror and more like a cry for understanding. I’m reminded of a late-night screening at an old revival house, where the audience fell into complete silence during Larry’s first transformation – not out of dated effects or melodramatic acting, but because we recognized something brutally honest in his loss of control.

The film’s influence extends far beyond its immediate horror descendants. You can trace its DNA through the body horror of David Cronenberg, the psychological transformations in Black Swan, and even the identity crises at the heart of modern superhero films. When Bruce Banner struggles with his inner Hulk, he’s walking the same thorny path as Larry Talbot. The recent surge in werewolf narratives in young adult fiction and television series like Teen Wolf draws directly from this wellspring, though often missing the profound tragedy that made the original so powerful.

Perhaps most significantly, The Wolf Man emerged at a pivotal moment in American cinema. Released just days after Pearl Harbor, it spoke to a nation grappling with transformation and violence on a global scale. The film’s Europe is a place of ancient curses and primal forces, reflecting America’s own anxieties about the Old World’s capacity for savagery. Yet it’s also a deeply personal story about father and son, about homecoming and belonging, themes that resonated deeply with audiences facing separation and loss.

Watching The Wolf Man today, in an era of unprecedented anxiety and transformation, its power only grows. We understand Larry’s curse in new ways – as addiction, as mental illness, as the weight of secrets we fear to share. When he peers into those mirrors, searching for signs of the change, he reflects our own fears of losing control, of becoming something our loved ones can’t recognize or accept.

The Wolf Man remains a masterpiece of horror cinema not because it frightens us with its monster, but because it makes us empathize with him. In Larry Talbot’s curse, we see our own struggles with destiny, identity, and the beast that might lurk within us all. When the autumn moon is bright and the wolfbane blooms, his howl still echoes through the halls of horror history, reminding us that sometimes the most terrifying transformations are the ones we can’t prevent.