In the murky depths of Universal’s 1954 masterpiece, terror swims with prehistoric grace. The Creature from the Black Lagoon emerges like a fever dream from humanity’s deepest ancestral memories – when we were nothing but prey in primordial waters, our scales not yet shed for skin.

Jack Arnold’s aquatic nightmare begins in the embrace of the Amazon, where science crashes headlong into myth. A fossilized claw sets our story in motion, but it’s the living breath of the jungle that pulls us under. The Rita, our weathered vessel of discovery, pushes through waters that haven’t changed since the Devonian period, carrying a crew whose modern certainties are about to be gloriously shattered.

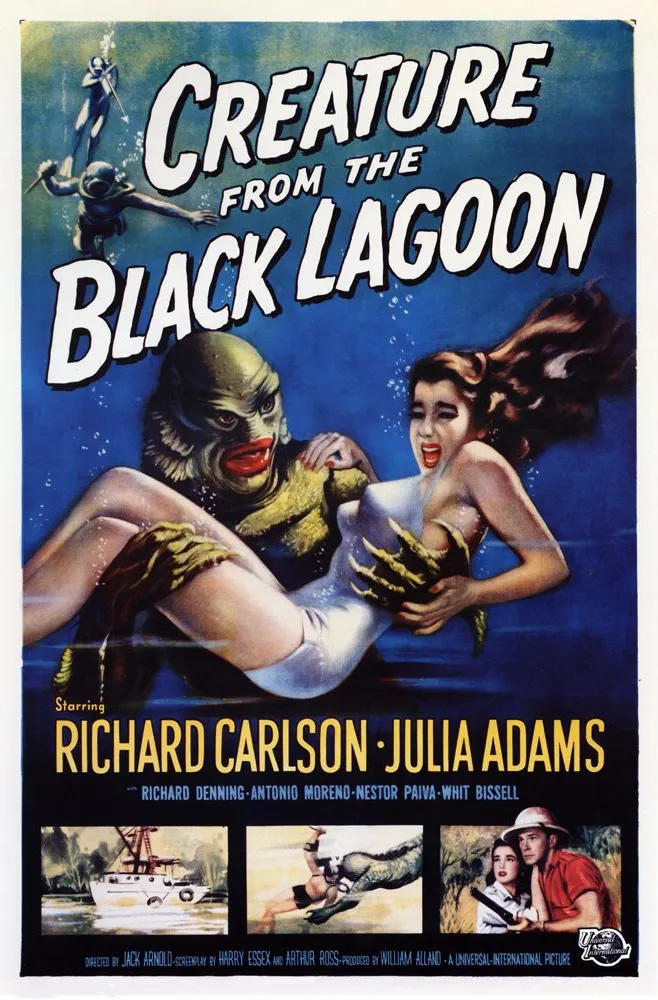

The film’s genius lies not in its monster, though the Gill-man remains one of cinema’s most haunting creations. No, the true power flows from its underwater ballet – a dance of predator and prey that transforms into something far more primal. When Julie Adams’ Kay Lawrence glides through the lagoon’s waters in that iconic white swimsuit, the creature mirrors her movements below, creating a sequence that transcends horror to become pure cinema. It’s beauty and beast in perfect synchronicity, a courtship ritual that predates humanity itself.

The underwater cinematography, revolutionary for its time, creates a suspended reality where human and prehistoric worlds collide. Ricou Browning’s underwater performance as the Gill-man is a masterwork of fluid movement – every gesture telling the story of a being both ancient and tragically aware of its own isolation. The 3-D presentation, while lost to most modern viewers, served not as mere gimmick but as a window into this submerged world where depth itself becomes a character.

What strikes me most profoundly about the Creature From The Black Lagoon is how it captures the essence of discovery – both its wonder and its terror. The initial expedition, led by Dr. Carl Maia’s discovery of the fossilized claw, mirrors humanity’s eternal push into unknown territories. It’s a reminder that every great discovery comes with a price, every new frontier holds its own guardians.

Richard Carlson’s Dr. David Reed and Richard Denning’s Dr. Mark Williams embody science’s dueling approaches to the unknown – respect versus domination. Their conflict mirrors our own struggle with nature, a theme that resonates even more powerfully today than in 1954. The Gill-man becomes a living rebuke to human hubris, a reminder that there are depths we were never meant to plumb.

Universal’s creature design, brought to life through the unsung brilliance of Milicent Patrick, creates something far more complex than a simple monster. The Gill-man’s eyes hold an almost human intelligence, while its form suggests an evolutionary path not taken. It’s both foreign and strangely familiar, like looking into a funhouse mirror of our own aquatic origins.

The film’s pacing builds like a rising tide. Each encounter with the creature escalates the tension, from curious observation to violent confrontation. The use of Captain Lucas’s native poison to flush out the beast speaks to mankind’s eternal urge to control what it fears, while the creature’s resistance reminds us that nature always holds the final card.

What elevates this beyond mere monster movie mechanics is its underlying current of loneliness. The Gill-man’s fascination with Kay suggests not just primitive urges but a recognition of beauty, of something that speaks to its own isolation in a world that has moved on without it. This is a creature that remembers when the world was young, when its kind ruled the waters that humans now dare to invade.

The Black Lagoon itself becomes a character – a pocket of prehistoric time where modern rules hold no sway. The jungle presses in, the water holds secrets, and every ripple might herald emergence of something we’ve forgotten how to fear. Arnold’s direction creates a pressure-cooker atmosphere where science, romance, and primal terror swirl together in the humid Amazon air.

Every time I revisit this film, I’m struck by how it manages to create suspense through suggestion rather than spectacle. The way the creature’s presence is first hinted at – a ripple here, a shadow there – builds a sense of anticipation that modern horror often sacrifices for quick thrills. The film understands that what we imagine lurking in those dark waters is far more terrifying than anything that could be explicitly shown.

The film’s influence ripples through cinema history like the Gill-man’s wake. You can trace its DNA through Jaws, The Shape of Water, and countless other aquatic nightmares. Yet none quite capture its perfect balance of beauty and horror, of sympathy and terror. The Gill-man joins Universal’s pantheon of monsters not through accumulated body count but through its tragic nobility – a reminder that sometimes the monster is simply trying to protect its home from the real invaders.

What makes The Creature from the Black Lagoon endure is its understanding that true horror lies not in the monster’s appearance but in its meaning. It represents everything we’ve lost touch with – our own evolutionary past, our connection to the natural world, and our recognition that we are not the only form of intelligence to emerge from Earth’s long dreaming.

The film’s final moments, as the creature retreats wounded into its domain, leave us not with triumph but with something closer to regret. We’ve won nothing except confirmation of our own destructive nature. The Gill-man slips away, perhaps to die, perhaps to wait – a guardian of ancient waters that will outlast all our scientific endeavors and proud certainties.

The Creature from the Black Lagoon reminds us that sometimes the most terrifying discoveries are those that make us question our place in the natural order. It’s a film that gets under your skin and into your gills, leaving you with the unsettling sensation that somewhere, in waters we’ve yet to fully explore, something still waits – watching, swimming, remembering when the world was its own.

In today’s era of CGI monsters and jump scares, this patient, poetic nightmare feels more relevant than ever. It’s a master class in suggestion over shock, in building atmosphere through architecture of dread rather than mere effects. The Gill-man still swims through our collective unconscious, reminding us that some fears – and some films – are timeless.