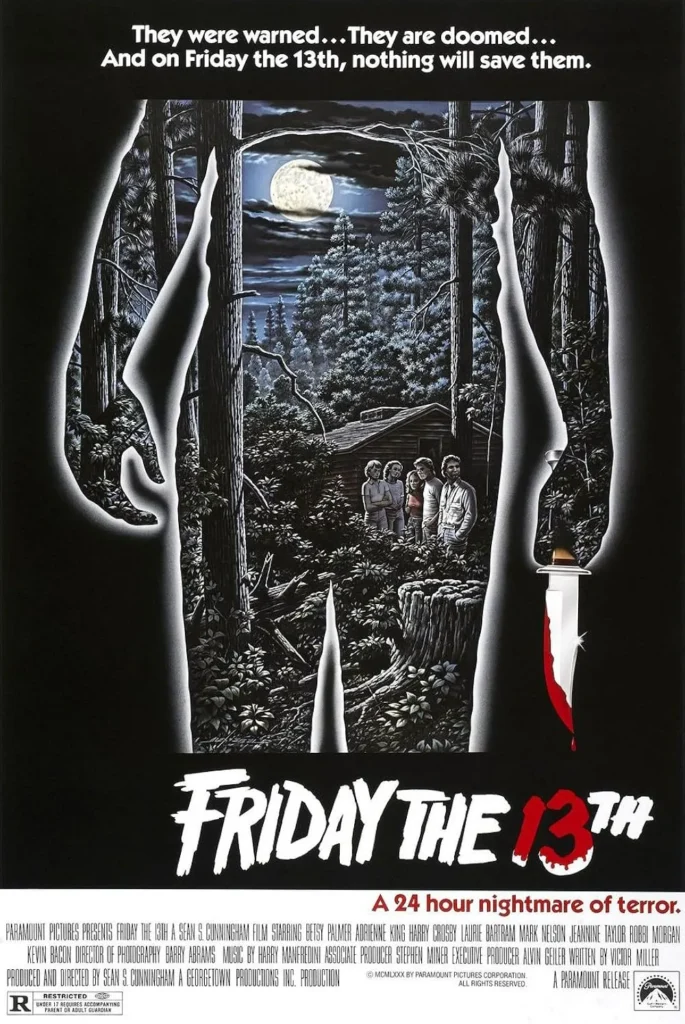

In the dying light of the 1970s, as America stumbled drunk and paranoid into a new decade, Sean S. Cunningham unleashed a primal scream that would echo through horror cinema forever. Friday the 13th (1980) isn’t just a movie – it’s a razor-sharp reflection of our darkest pastoral nightmares, where summer camp innocence drowns in the black waters of revenge.

The film opens like a match strike in darkness: two camp counselors, their laughter echoing through empty cabins, meet their maker in a burst of violence that sets the tone. But it’s what follows that really twists the knife. We’re dropped into a sun-drenched Camp Crystal Lake years later, where fresh-faced counselors arrive like lambs to the slaughter, their optimism as fragile as moth wings in a storm.

Tom Savini’s practical effects work here isn’t just gore – it’s poetry written in red. Each death scene is orchestrated like a twisted opera, with arrows piercing throats and axes finding homes in unsuspecting faces. The violence isn’t gratuitous; it’s ceremonial, each kill a sacrificial offering to the angry spirit of Crystal Lake itself.

But it’s Betsy Palmer’s Mrs. Voorhees who emerges as the true phantom of this fever dream. When she appears in the third act, Palmer transforms from sweater-wearing soccer mom to vengeful fury in the blink of an eye. Her performance hits like a sledgehammer to the spine – raw, unhinged, and devastating. She’s not just another movie monster; she’s every parent’s grief crystallized into pure, murderous rage.

The film’s atmosphere is thick enough to choke on. Cinematographer Barry Abrams turns the woods into a labyrinth of shadows, where every tree could hide death, and every cabin becomes a potential tomb. The legendary “ki ki ki, ma ma ma” score by Harry Manfredini (actually “kill kill kill, mom mom mom”) burrows into your brain like a parasite, triggering fight-or-flight responses with pavlovian precision.

Adrienne King’s Alice emerges as our “final girl,” but she’s not just running and screaming – she’s evolving, transforming from wide-eyed camp counselor to hardened survivor before our eyes. Her final confrontation with Mrs. Voorhees on the shores of Crystal Lake isn’t just a fight for survival; it’s a primal battle between youth and age, innocence and vengeance, future and past.

What makes Friday the 13th truly remarkable is how it captures the death of American innocence. Camp Crystal Lake is every summer camp that ever existed, every place where parents trusted their children would be safe. The film taps into that universal fear – that the institutions we trust might become killing grounds, that the authority figures meant to protect us might be the ones we should fear most.

The infamous ending, with young Jason emerging from the lake like a water-logged revenant, isn’t just a jump scare – it’s a statement. The past never stays buried, trauma breeds trauma, and violence begets violence in an endless cycle. It’s a punch to the gut that leaves audiences gasping, questioning whether what they just saw was real or a nightmare bubble rising from Crystal Lake’s murky depths.

Made for pocket change ($550,000) but grossing nearly $40 million domestically, Friday the 13th proved that American audiences were hungry for something raw and untamed. While critics turned up their noses, dismissing it as Halloween’s cheaper cousin, they missed the point entirely. This wasn’t about sophistication – it was about tapping directly into the jugular of American fear.

The film’s power lies not in its originality but in its brutal efficiency. Every frame serves a purpose, every death advances the story, and every moment of quiet builds tension for the next explosion of violence. It’s a masterclass in pacing, proving that sometimes the most effective horror comes not from what you show, but from what you withhold.

Looking back through the blood-tinted lens of time, Friday the 13th stands as more than just another slasher film. It’s a watershed moment in horror cinema, a dark mirror held up to American suburbia’s worst fears, and a testament to the power of raw, uncompromising filmmaking. Like Crystal Lake itself, it holds dark secrets beneath its surface, waiting to pull under anyone who dares to look too deeply.

The legacy of Friday the 13th isn’t just in its endless sequels or its iconic imagery – it’s in how it changed the DNA of horror itself. It showed that terror could lurk in the most innocent places, that monsters could wear friendly faces, and that sometimes the most effective scares come not from supernatural threats, but from the depths of human grief and rage.

As Mrs. Voorhees’ head rolls and Alice drifts alone on Crystal Lake’s morning mist, we’re left with a profound unease that no amount of daylight can dispel. This is horror that leaves marks, both on the genre and on our collective psyche. Friday the 13th isn’t just a movie that scared audiences – it’s a movie that showed us why we were already scared, reflecting back our own darkest fears about safety, trust, and the price of negligence.

In the end, Friday the 13th remains a brutal, beautiful nightmare – one that we can’t help but revisit, even as it continues to draw blood with every viewing. It’s a reminder that sometimes the most effective horror isn’t about supernatural monsters or elaborate special effects, but about the simple, primal fear of being alone in the dark, knowing something out there wants you dead.

Forty-plus years later, the waters of Crystal Lake still run red with influence, and its ripples continue to be felt in every slasher film that dares to follow in its bloody footprints. Some movies scare you for a moment – Friday the 13th scars you for life.