Get Out burrows into your consciousness like a parasite, spreading its tendrils through the deepest recesses of your mind until you can’t tell where your thoughts end and Jordan Peele’s masterwork begins. It’s a film that doesn’t just showcase horror – it weaponizes your own discomfort against you, turning every polite smile and well-meaning comment into a dagger aimed straight at your soul. The first time I watched this film, I felt my skin crawl with each passing minute, recognizing the subtle dance of microaggressions that Peele orchestrates with devastating precision.

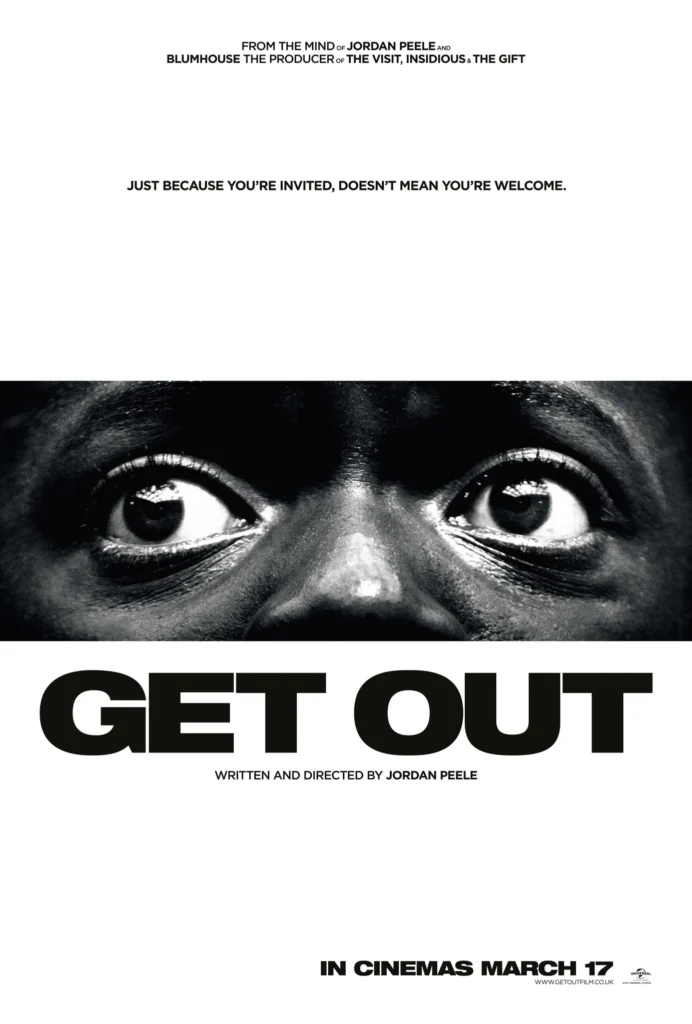

In the hands of a lesser filmmaker, this story of Chris Washington’s weekend from hell could have been just another entry in the tired “meet the parents” genre. But Peele transforms this familiar setup into something far more insidious, creating a nightmare that feels as real as your morning coffee. Daniel Kaluuya’s eyes become our window into this twisted world – those eyes that speak volumes in their silence, that scream in their stillness, that see everything while revealing nothing. There’s a moment early in the film where Chris stands in front of the mirror, his reflection a portrait of uncertainty, and I felt every ounce of his hesitation, his instinctive knowledge that something isn’t right.

The Armitage estate is American racism dressed in its Sunday best, all manicured lawns and liberal platitudes. Bradley Whitford’s Dean would vote for Obama a third time if he could, don’t you know? His performance is a masterclass in hidden menace, every seemingly progressive statement dripping with something darker underneath. Allison Williams as Rose delivers a performance that shifts like quicksand beneath your feet – what initially seems like allyship reveals itself as something far more sinister. Catherine Keener’s Missy stirs her teacup with surgical precision, each clink against porcelain a hypnotic drumbeat leading Chris deeper into the abyss. The sunken place – Peele’s masterstroke of metaphorical horror – isn’t just a plot device; it’s the crystallization of Black America’s worst fears, a state of conscious paralysis where you can see everything but control nothing.

The film’s cinematography by Toby Oliver is a masterclass in unease. Every frame feels slightly off-kilter, like a picture hung just crooked enough to bother you but not enough to fix. The camera lingers on faces a beat too long, transforming casual conversations into psychological warfare. The way Oliver frames the party scene, with Chris isolated in a sea of white faces, creates a suffocating sense of otherness that resonates with anyone who’s ever been the only person of color in a room. When Betty Gabriel’s Georgina smiles and says “no” with tears streaming down her face, it’s not just acting – it’s a visualization of generational trauma trapped behind a mask of servitude. That scene haunted me for weeks after my first viewing, the perfect encapsulation of forced assimilation and lost identity.

Michael Abels’ score deserves its own chapter in the annals of horror music. The way he weaves African-American voices through the soundtrack creates a ghostly chorus of the displaced and forgotten, their harmonies serving as both warning and lament. “Sikiliza Kwa Wahenga” – the film’s main theme – isn’t just background music; it’s the voices of ancestors screaming “Listen to the ancestors… run!” The score builds tension with the precision of a surgeon, knowing exactly when to whisper and when to scream.

But what elevates Get Out beyond mere horror is its savage wit. Lil Rel Howery’s TSA agent Rod provides more than comic relief – he’s the voice of sanity in a world gone mad, the Greek chorus who says what we’re all thinking. Every line he delivers lands with perfect timing, providing necessary moments of levity that make the horror hit even harder when it returns. The humor doesn’t undercut the horror; it amplifies it, making the terrible moments land with even more impact because we’ve been allowed to breathe.

Peele orchestrates every element with the precision of a surgeon and the soul of a poet. The deer motif isn’t just symbolic – it’s a through-line that connects the film’s opening tragedy to its climactic moment of redemption. The casual racism of the party guests isn’t just uncomfortable – it’s a damning indictment of liberal white America’s obsession with Black bodies and culture. The way these wealthy white people touch Chris without permission, comment on his physical attributes, and try to connect with him through their knowledge of Tiger Woods is skin-crawling in its accuracy. Every seemingly throwaway line (“You know I can’t give you the keys, right, babe?”) becomes a loaded gun on the wall, waiting to go off in the third act.

The film’s exploration of the commodification of Black bodies isn’t subtle, but it shouldn’t be. In an era where we’re still fighting about whether Black lives matter, Peele takes the conversation to its logical, horrifying conclusion. The Armitages don’t hate Black people – they want to become them, to possess them, to wear them like designer suits. It’s colonialism given surgical precision, slavery reborn through medical marvel. The auction scene, played out in broad daylight with nothing but the gentle clink of teacups and polite conversation, is more terrifying than any midnight graveyard could ever be.

The genius of Get Out lies in how it makes the metaphorical literal. The sunken place isn’t just a plot device – it’s what it feels like to be silenced, to be talked over, to be told your experiences aren’t valid. When Chris sinks into that void, we sink with him, and that feeling of helpless awareness is more terrifying than any jump scare could ever be. I remember watching this scene for the first time, feeling my own breath catch in my throat as Chris descended into that endless darkness, understanding on a visceral level what it means to be present but powerless.

The film’s technical brilliance extends beyond its obvious elements. The sound design creates a world where silence becomes threatening and familiar sounds take on sinister new meanings. The editing builds tension through precision rather than tricks, knowing exactly how long to hold a shot to maximize discomfort without breaking the spell. Even the production design tells a story – the Armitage home is full of subtle colonial touches, artifacts of conquest displayed with proud ignorance of their implications.

As the film builds to its bloody climax, Peele never loses control of his narrative. The violence, when it comes, feels earned and necessary. Chris’s journey from passive observer to active participant in his own survival is a testament to both Kaluuya’s nuanced performance and Peele’s masterful direction. The moment when Chris stuffs his ears with cotton – literally refusing to listen to white voices – is both dramatically satisfying and thematically perfect. It’s a rejection of the very system that sought to control him, using the tools of oppression as means of liberation.

In the end, Get Out isn’t just a horror film about racism – it’s a document of our times, a mirror held up to society that shows all our ugly truths in stunning clarity. It’s a film that understands that the scariest monsters aren’t the ones that hide under our beds, but the ones that invite us in for tea and tell us how much they admire Tiger Woods. It’s a wake-up call, a warning, and a masterpiece all rolled into one.

When those red and blue lights appear in the final scene, every Black person in the audience holds their breath. We know what those lights usually mean in our stories. But Peele gives us something different – not just an ending, but a beginning. Rod’s arrival in his TSA vehicle isn’t just a rescue; it’s a revolution, a moment where the system works for us instead of against us.

Get Out changed the landscape of American horror, not just because it was successful, but because it was necessary. It took the conversations we were having in private and screamed them from the screen. It made the personal universal and the political visceral. Five years later, its power hasn’t diminished – if anything, it’s grown stronger, more relevant, more essential.

This isn’t just filmmaking – it’s cultural exorcism, drawing out our demons so we can face them in the harsh light of day. Jordan Peele didn’t just make a horror movie; he created a new language for talking about race in America, one that cuts through the polite fiction of post-racial society and forces us to confront the monsters we try so hard to ignore. In the end, Get Out isn’t just a film you watch – it’s a film that watches you back, asking the uncomfortable question: which part of this horror story do you see yourself in?