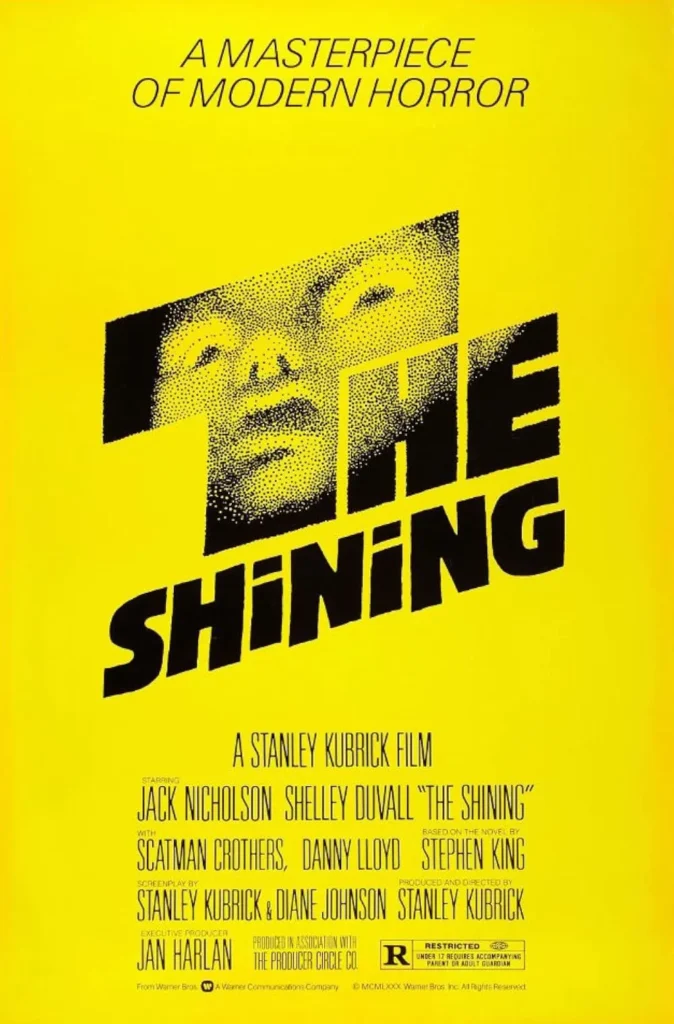

The Shining burrows into your skull like a nightmare that won’t wash away, a fever dream dressed in Steadicam floating through endless corridors of American darkness. Kubrick’s masterpiece of psychological horror doesn’t just show us madness – it makes us live inside it, breathing the stale air of the Overlook Hotel until we’re not sure if we’re watching Jack Torrance lose his mind or losing our own.

I’ve watched this film more times than I can count, each viewing revealing new layers of terror beneath its pristine surface. The genius lies not in jump scares or gore, but in the slow-burning dread that creeps up your spine like frost on a Colorado window. Kubrick, that magnificent bastard, takes King’s haunted house tale and transforms it into something far more sinister – a meditation on the rot eating away at the foundations of the American family.

Jack Nicholson’s Jack Torrance isn’t just a man going mad – he’s the death of the American Dream in slow motion, his writer’s block a metaphor for creative impotence, his alcoholism a stand-in for all our addictions and weaknesses. When he sits at that typewriter, pounding out endless repetitions of “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy,” it’s not just his sanity breaking – it’s the myth of the self-made man shattering into a thousand jagged pieces.

The Overlook itself becomes a character, its impossible architecture (windows where no windows should be, doors that open onto nowhere) creating a maze of the mind that mirrors Jack’s descent. The camera glides through these spaces like a ghost, Kubrick’s revolutionary use of the Steadicam creating a sense of otherworldly presence. We’re not watching this horror unfold – we’re floating through it, untethered from reality, lost in the labyrinth.

Shelley Duvall’s Wendy Torrance deserves special mention. Her performance, born from Kubrick’s notorious perfectionism (127 takes for a single scene – a record that stands to this day), captures something raw and primal about maternal terror. Her wide-eyed fear isn’t acting – it’s the real thing, captured on celluloid through Kubrick’s relentless pursuit of authenticity. When she swings that baseball bat at Jack, her hands trembling, her voice cracking, we’re watching both character and actor pushed to their absolute limits.

The film’s soundscape is a masterclass in audio terror. Kubrick layers Penderecki’s discordant classical pieces with a precision that would make a brain surgeon envious. The music doesn’t just accompany the horror – it becomes it, those screaming strings and thundering percussion creating a sonic landscape of pure psychological disturbance.

But what elevates The Shining above mere horror is its layered symbolism, its deeper concerns with America’s buried sins. The hotel, built on an Indian burial ground, becomes a monument to genocide. The recurring number 42 (appearing in Danny’s jersey, the number of cars in the parking lot, even hidden in Room 237) points to 1942 and the Holocaust. The film is haunted not just by ghosts, but by the weight of history itself.

Danny Lloyd’s Danny Torrance, with his psychic “shining,” becomes our window into this world of adult madness. His tricycle rides through the hotel’s corridors (shot at child height, creating a sense of vulnerable intimacy) show us the horror through innocent eyes. When he encounters the Grady twins, standing like pale harbingers of doom in their matching blue dresses, the moment burns itself into your retinas. “Come play with us, Danny… forever… and ever… and ever.” It’s childhood corrupted, innocence shattered.

The maze sequence in the finale isn’t just a chase – it’s a metaphor for the whole damn film. Jack, lost in the labyrinth of his own making, freezes to death while trying to murder his family. The cycle of violence ends not with a bang but with a whimper, Jack becoming just another ghost in the Overlook’s haunted halls.

That final shot – the slow zoom into the July 4th, 1921 photograph, where Jack’s face grins out at us from the past – is perhaps cinema’s greatest twist of the knife. The hotel hasn’t possessed Jack; it’s always had him. He’s always been the caretaker, trapped in an endless cycle of American violence, smiling that terrible smile while the band plays “Midnight, the Stars and You” into eternity.

What makes The Shining truly terrifying isn’t its ghosts or its gore – it’s its suggestion that madness isn’t something that happens to us suddenly, but something that’s always been there, waiting in the corridors of our minds like those twins in their blue dresses. The real horror isn’t supernatural at all – it’s the recognition that the monster isn’t in the hotel, but in the mirror.

Kubrick’s obsessive attention to detail (shooting for over a year, driving his actors to the brink of breakdown, designing every frame with mathematical precision) creates a film that feels less like entertainment and more like a transmission from some darker dimension. The impossible spaces of the Overlook, the subtle continuity “errors” that create a sense of spatial wrongness, the carefully placed Native American decorations that hint at buried historical trauma – everything serves the film’s deeper purpose of psychological destabilization.

The Shining doesn’t just show us horror – it makes us complicit in it. We become like Danny, cursed with the ability to see the truth behind the façade, unable to look away as the madness unfolds. The film’s genius lies in making us question our own sanity as we watch Jack lose his. Are we seeing ghosts, or just the projections of a fractured mind? Is the hotel haunted, or is it simply a mirror reflecting back our own capacity for violence?

Time has only sharpened the film’s edges. What seemed like excessive theatrical performance from Nicholson in 1980 now reads as prophetic – a portrait of masculine rage and impotence that feels more relevant with each passing year. The film’s themes of isolation, addiction, and family violence resonate even more powerfully in our age of digital disconnection and social fragmentation.

The Shining isn’t just a horror film – it’s a descent into the dark heart of the American psyche, a journey through the maze of our collective unconscious. It’s a film that shows us monsters and then forces us to recognize them as ourselves. In the end, we’re all just ghosts in the Overlook, trapped in our own personal mazes, typing the same words over and over, hoping they’ll somehow mean something different this time.

Like the hotel itself, The Shining is a masterpiece that seems to change every time you look at it, revealing new horrors, new meanings, new ways to make you question your own grip on reality. It’s a film that doesn’t just get under your skin – it lives there, like a splinter in your mind, reminding you that sometimes the scariest ghosts are the ones we carry within ourselves.

Come play with us, indeed. Forever… and ever… and ever.