The Canadian film that codified the slasher formula four years before Halloween—and it’s still one of the scariest movies ever made.

Quick Facts Panel

- Director: Bob Clark

- Writer(s): Roy Moore (original screenplay “Stop Me”), Timothy Bond (rewrites), Bob Clark (dialogue alterations)

- Runtime: 98 minutes

- Rating: R (MPAA) | 18 (BBFC)

- Budget: $686,000 CAD (~$4.1 million today)

- Box Office: $4,053,000 worldwide ($1.3M Canada, ~$1M US)

- Release Date: October 11, 1974 (Canada) | December 20, 1974 (US)

- Subgenre(s): Proto-Slasher, Psychological Horror, Holiday Horror, Home Invasion

- CreepyCinema Scare Rating: 9/10 – Masterclass in atmospheric terror

- Notable Cast: Olivia Hussey, Keir Dullea, Margot Kidder, John Saxon, Andrea Martin

- Cinematographer: Reginald H. Morris

- Music: Carl Zittrer

- Production Companies: Vision IV, Canadian Film Development Corporation, Film Funding Ltd. of Canada, Famous Players

- Distributors: Warner Bros. (US), Ambassador Film Distributors (Canada)

- Awards: 3 Canadian Film Awards (1975) – Best Sound Editing (Kenneth Heeley-Ray), Best Film Editing (Stan Cole), Best Actress (Margot Kidder, for both A Quiet Day in Belfast and Black Christmas)

The Essence

Black Christmas didn’t just predate Halloween by four years—it codified the slasher formula that would define a genre. This Canadian horror masterpiece introduced POV killer shots, a formative early final girl trope, and the iconic “the call is coming from inside the house” concept while delivering a sophisticated feminist critique that remains chillingly relevant 50 years later. Director Bob Clark’s genius lies in restraint: the killer “Billy” remains almost entirely unseen, his identity forever mysterious, his presence in the attic creating perpetual dread that outlasts any modern jump scare. What makes Black Christmas truly terrifying isn’t what it shows—it’s what it refuses to reveal, and the ambiguous ending will haunt you long after the credits stop rolling.

Plot Synopsis

The Setup: A Killer Already Inside

The film opens with one of horror cinema’s most influential shots—a POV sequence showing an unknown figure approaching the Pi Kappa Sigma sorority house during a Christmas party. Using a revolutionary head-mounted camera rig, we watch through the killer’s eyes as he climbs the exterior trellis and enters through the attic window. Clark’s first-person stalking, achieved with a head-mounted rig, prefigures Halloween’s opening and helped normalize killer-POV language in slashers.

Inside, we meet the sorority sisters preparing for Christmas break. Jess Bradford (Olivia Hussey) serves as our intelligent, rational protagonist dealing with an unplanned pregnancy. Barb Coard (Margot Kidder) provides darkly comic relief as the perpetually drunk sister with a razor-sharp tongue. Clare Harrison (Lynne Griffin) embodies innocence as the virginal first victim. Phyl Carlson (Andrea Martin) offers supportive presence as the level-headed friend. Mrs. Mac (Marian Waldman), the alcoholic housemother hiding bottles throughout the house, completes the ensemble.

The sorority receives an obscene phone call from “The Moaner”—graphic sexual babbling that makes everyone uncomfortable. When Barb taunts the caller by giving her number as “FELLATIO 20880,” his tone shifts from merely obscene to threatening: “I’m going to kill you.” The caller’s voice alternates between multiple personalities, screaming about “Agnes” and “the baby” in incoherent fragments suggesting profound psychological fracture.

Clare is packing when Billy emerges from her closet and suffocates her with a plastic dress bag in a genuinely shocking sequence shot with handheld camera in an actual closet. Billy drags her body to the attic and positions her corpse in a rocking chair by the window with a doll in her lap—a grotesque tableau suggesting enforced motherhood. This iconic image remains visible throughout the film from outside but goes completely unnoticed.

A crucial feminist subplot emerges: Jess reveals to her boyfriend Peter Smythe (Keir Dullea) that she’s pregnant and plans an abortion, prioritizing her career ambitions. Peter becomes increasingly unhinged, pressuring her to marry him using language mirroring pro-life rhetoric. This scene, just one year after Roe v. Wade, establishes the film’s progressive underpinnings. Peter’s controlling behavior and emotional volatility—punctuated by a botched piano recital where he destroys the instrument in manic rage—make him the prime suspect throughout.

The Descent: Institutional Failure and Escalating Terror

When Clare’s father arrives to pick her up and she doesn’t appear, police initially dismiss the concerns. This institutional indifference becomes increasingly pronounced—authorities only take women seriously when men (fathers, boyfriends) validate their fears. A secondary victim, 13-year-old Janice from a nearby park, is found murdered, increasing urgency while diverting police attention from the sorority house.

Mrs. Mac discovers Clare’s body in the attic and is immediately killed by Billy, who drives a crane hook into her face. Her body is hung among the attic’s forgotten relics. Billy’s phone calls continue throughout, becoming more disturbing as he alternates voices: “Billy, what your mother and I must know is, where did you put the baby? Where did you put Agnes?” He sings “Bye, Baby Bunting,” a lullaby underscoring his maternal obsession.

Lieutenant Kenneth Fuller (John Saxon) finally takes action, installing phone-tapping equipment to trace Billy’s calls. The sorority must keep him on the line long enough for a trace—a sequence that remains gripping through patient pacing and mounting dread.

During Christmas carolers singing “O Come, All Ye Faithful” outside, Billy enters Barb’s room and murders her with a crystal unicorn figurine—ironic symbols of purity killing the film’s most sexually liberated character. The scene masterfully juxtaposes angelic melodies with brutal violence, cutting between Jess listening downstairs and the savage attack above. Only the raising of the unicorn is shown, not actual impacts, yet the sequence remains one of horror cinema’s most effective kill scenes.

Phyl discovers Barb’s body and is immediately killed, left with the others in the attic’s macabre gallery.

The Climax: The Revelation (⚠️ SPOILERS)

A phone call is successfully traced—and the truth is terrifying: the calls are coming from inside the house. The killer has been living in the attic the entire time. Sergeant Nash delivers the famous line: “Jess, the caller is in the house. The calls are coming from the house!”

Jess finds Barb and Phyl’s bodies and glimpses Billy through a cracked door—viewers see only a shadowy figure and a single reddish eye in one of cinema’s most stomach-churning moments. She flees to the basement and locks herself in. Peter breaks through a window trying to enter; in panic and confusion, Jess kills him with a fire poker, believing him to be the killer.

Police arrive and find her unconscious, cradling Peter’s bloodied corpse. They conclude Peter was the killer—”they always knew it was the boyfriend”—and leave after posting only one officer outside. Jess is sedated and left alone to sleep in her bedroom, next to the room where she discovered her murdered friends.

The true ending delivers one of horror’s most disturbing conclusions. The camera slowly tracks through the now-quiet house as police depart, revealing they never searched the attic. The hatch opens, showing Mrs. Mac’s and Clare’s corpses still positioned there, Clare forever rocking by the window. Billy’s muttering continues as the phone begins ringing, suggesting he has killed the guard and Jess is his next victim. The credits roll in silence except for unanswered ringing, leaving Jess’s fate completely ambiguous.

Warner Bros. executives demanded Bob Clark change this ending to reveal the killer’s identity, but Clark refused—this ambiguity gives the film its lasting, unforgettable power.

The Horror Breakdown

What Makes It Scary

Primary Fear Exploited: Violation of safe space. The sorority house—symbol of female community and sanctuary—becomes a trap. Billy’s presence in the attic, literally above and overlooking the women’s private spaces, perverts domestic security. The genius of “calls from inside the house” transforms home from haven to horror.

Scare Techniques:

- Atmosphere over jump scares: Slow, deliberate pacing mirrors growing paranoia

- The power of the unseen: Billy remains almost entirely obscured—we glimpse only hands, a single eye, shadows. This anonymity makes him “Every Man,” more terrifying than any revealed face

- Weaponized sound: Ordinary sounds become dread-inducing—telephone rings, footsteps, breathing

- POV voyeurism: Revolutionary camera work puts audiences uncomfortably in the killer’s perspective

- Juxtaposition: Christmas cheer and caroling colliding with savage violence

- Institutional dismissiveness: Police not taking women seriously adds real-world horror

- Psychological warfare: The obscene phone calls feel “almost as assaultive as physical violence”

Most Terrifying Scenes (With Approximate Timestamps):

1. Clare’s Suffocation (Opening 10 minutes): Shot with handheld camera in an actual closet for genuine claustrophobic terror. Her wide eyes visible through transparent plastic convey a “haunting mix of terror and disbelief.” The death is intimate, up close, protracted. Actress Lynne Griffin’s surprise was authentic—she didn’t know when Billy would emerge. She poked nose holes in the bag and stuffed the opening in her mouth to breathe, relying on swimming skills to hold her breath for extended takes.

2. Clare’s Corpse in the Attic (Recurring): Billy arranges her body in a rocking chair with a doll in her lap, creating an iconic “death mask” expression. Police visit multiple times without looking up. The grotesque tableau combines childhood innocence with death, suggesting motherhood as woman’s only acceptable role. The image recurs throughout, visible through the attic window in exterior shots—a corpse hidden in plain sight.

3. The Eye in the Doorway (Final Act): After discovering bodies, Jess looks up to see a single eye peering through a door crack—the only clear detail of Billy ever shown. This “stunning voyeuristic shot” makes stomachs “somersault,” representing both fragmented body and fractured psyche. It’s the moment the abstract threat becomes horrifyingly real.

4. Barb’s Murder with Glass Unicorn (Mid-Film): While carolers sing “O Come, All Ye Faithful” outside, Barb is stabbed repeatedly. The scene “sways between angelic melodies and brutality,” with Jess listening downstairs unaware her friend is dying. Only the unicorn being raised is shown, not impacts—violence implied rather than shown. One of horror’s most “effectively terrifying set pieces.”

5. “The Calls Are Coming From Inside the House” (Final Act): When police trace reveals the killer’s location, Sergeant Nash delivers the iconic line. “All it took to push horror into overdrive was a single line of dialogue.” The revelation that Billy has been inside all along transforms the entire viewing experience retroactively.

6. Jess’s Basement Chase (Climax): Described as “one of the most terrifying killer chase scenes in horror movies” where “you can imagine him simply ripping her apart with his bare hands.” The sequence’s power comes from Billy’s barely-seen presence and Jess’s mounting desperation.

7. The Final Shot—The Phone Rings Again: After police remove bodies (except Clare still in attic), sedated Jess is left alone. Camera pans to attic, phone rings. Billy remains alive in the house. One of horror cinema’s greatest twist endings that “keeps fear alive long after credits roll.”

Scariest Moment (Spoiler-Free for First-Time Viewers): The revelation about where the phone calls are actually coming from. This single moment of realization transforms everything that came before and creates an entirely new level of terror.

Gore & Intensity Levels

Violence Level: 6/10 Black Christmas explicitly avoids “overly bloody death sequences,” relying on implication rather than exhibition. The kills include:

- Clare’s suffocation (off-screen, plastic bag visible on corpse later)

- Barb’s stabbing (only weapon raising shown, dried blood on arm afterward)

- Mrs. Mac’s hook attack (cuts away before impact, minimal blood visible from distance)

- Officer’s throat slashing (shown sitting in car, bloody but quick)

- Peter’s bludgeoning (limited blood shown)

Gore Factor: 4/10 Most violence occurs just off-screen or in shadow. Bodies in bed appear “quite dark” with “little blood seen.” The film was considered “more graphic than television precursors” but remains restrained compared to later slashers. What makes it effective is context and suggestion—your imagination fills in the horror.

Psychological Intensity: 10/10 This is where Black Christmas truly excels. The film is heavily psychological over physical, creating dread through:

- Growing paranoia from the opening POV shot

- Claustrophobia (killer inside creates no escape)

- Violation (someone watching and touching belongings while unaware)

- Gaslighting (police don’t believe women)

- Institutional betrayal (authorities failing to protect)

- Dual threats (both killer and controlling boyfriend)

- Internal conflict (Jess’s pregnancy, abortion decision, career vs. traditional expectations)

The film “intertwines the unseen killer’s sexually-motivated violence and barely-repressed Freudian trauma with the abusive boyfriend’s increasingly unhinged spiraling,” making it “one of the scariest movies about navigating male rage.”

Supernatural Elements: No Billy is entirely human, which somehow makes him more terrifying. No mystical explanations, no supernatural powers—just a deeply disturbed individual who could be anyone, anywhere.

Characters & Performances

Main Cast

Jess Bradford – Olivia Hussey

The intelligent, determined protagonist at the film’s emotional center. An international star from Franco Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet (1968), Hussey signed on after her psychic told her she would “make a film in Canada that would earn a great deal of money.”

Performance Highlights: Hussey delivers a “grounded, magnetic performance” that “captures passion and yearning” while “carrying the weight of burden and fear without falling into typical Final Girl theatrics.” Her increasingly frantic cries—”Phyl. Barb. PLEASE ANSWER ME”—are delivered at “heartbreakingly anguished pitch.” She makes Jess feel like a complete person dealing with real issues (unplanned pregnancy, controlling boyfriend, career ambitions) rather than a horror movie archetype. As a formative early final girl, she helped establish the template alongside Sally Hardesty from The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (also 1974).

Character Arc: Jess begins as a woman in crisis, trying to maintain control of her body and future against both a controlling boyfriend and societal expectations. As the horror escalates, her survival instinct kicks in—but the film’s ambiguous ending denies her (and us) any real resolution or safety.

Fun Fact: Years later, Steve Martin told Hussey he’d seen Black Christmas 27 times and it was one of his favorite films—she assumed he meant Romeo and Juliet but was surprised when he specified Black Christmas.

Peter Smythe – Keir Dullea

Jess’s emotionally volatile boyfriend and red herring suspect. Best known as Dave Bowman in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Dullea was specifically sought by Clark based on that performance. Malcolm McDowell was originally offered the role but declined.

Performance Highlights: Dullea creates genuine tension through petulant antagonism and barely-controlled rage. His haphazard piano audition and violent destruction of the piano punctuate his unraveling psychology. The abortion confrontation scene showcases his ability to shift from pleading to threatening.

Character Arc: Peter’s arc remains deliberately ambiguous—is he the killer, or just an abusive boyfriend? The film suggests he’s innocent of murder but guilty of trying to control Jess’s body and future. His death at Jess’s hands represents both tragic misunderstanding and symbolic killing of male control.

Critical Note: Reviews remain divided—some praised the adult conflict and performance, while others felt Dullea appeared “way too old and European for the role” of a college student.

Barb Coard – Margot Kidder ⭐ 1975 Canadian Film Award Winner – Best Actress (for both A Quiet Day in Belfast and Black Christmas)

The brash, perpetually drunk sister who universally steals every scene. The Canadian actress (later Lois Lane in Superman 1978) was attracted to the role “because she was wild and out of control” rather than “conventional leading.”

Performance Highlights: Leonard Maltin specifically called Kidder’s performance “a standout.” Her drunk monologue about sea turtles mating at the zoo—delivered to Clare’s father—transitions from hilarious to emotionally painful. She delivers the film’s most memorable line: giving her phone number as “FELLATIO 20880.” Kidder brings depth to what could have been a one-note character, making Barb’s alcoholism both funny and sad.

Character Arc: Barb serves as comic relief but also represents female sexual liberation—she’s unapologetically crude, drinks openly, and speaks her mind. The film never judges her for this, even as she becomes a victim. Her death while carolers sing outside creates one of cinema’s most effective tonal juxtapositions.

Behind the Scenes: Kidder described filming as “fun” and bonded with Andrea Martin. She noted Olivia Hussey “was obsessed with falling in love with Paul McCartney through her psychic. We were a little hard on her for things like that.”

Lieutenant Kenneth Fuller – John Saxon

The professional, competent detective who actually takes the women seriously (eventually). Genre legend from the first giallo film The Girl Who Knew Too Much (1963), Saxon was Clark’s first choice but miscommunications led to Oscar-winner Edmond O’Brien being cast initially. When O’Brien arrived, his failing health from Alzheimer’s made the role impossible.

Performance Highlights: Saxon received an urgent call and traveled from New York to Toronto within two days. Despite having to hit the ground running, he delivers what critics consistently cite as a “cool comforting presence” and solid authority that grounds the film. He recalled Clark’s meticulous storyboards: “I could understand exactly what he needed, and the scene needed.”

Character Arc: Fuller represents institutional authority that finally listens to women—but his competence is ultimately undermined when police assume the wrong person is guilty and leave Jess vulnerable.

Phyl Carlson – Andrea Martin

The level-headed, supportive sister who serves as audience surrogate. Second City comedy troupe member (later SCTV and My Big Fat Greek Wedding fame), Martin replaced Gilda Radner, who dropped out one month before filming for Saturday Night Live commitments.

Performance Highlights: Martin’s naturalism contributes to the authentic group dynamic and “quaint lived-in hangout quality” of performances. Her understated approach makes her death more shocking—there’s no dramatic final confrontation, just sudden violence.

Legacy: Martin was the only original cast member appearing in the 2006 remake (different role), with Bob Clark serving as executive producer before his 2007 death.

Mrs. Mac – Marian Waldman

The alcoholic housemother who provides “highly pleasant and amusing” comic relief without undermining horror. The role was originally offered to Bette Davis, who declined. Clark based the character on his aunt.

Performance Highlights: Even Variety’s negative review singled out Waldman for praise as “the secretly alcoholic sorority house mother,” calling her performance “delightful.” Her discovery of Clare’s body and immediate death creates genuine shock—the film kills the comedy relief without warning.

Clare Harrison – Lynne Griffin

The innocent first victim whose corpse becomes the film’s most haunting image. Toronto native cast through her mother/casting agent, Griffin later starred in Curtains (1983).

Performance Highlights: Griffin shot her death scene in a real closet with handheld camera in just two takes. Her genuine surprise when Billy lunges created authentic terror. For extended corpse shots wearing an actual plastic bag, Griffin relied on swimming skills: “I could hold my breath for a long time and keep my eyes open without blinking.”

Standout Performances

Nick Mancuso as Billy’s Voice (Uncredited) creates genuinely terrifying vocal performance. When auditioning, Clark had Mancuso sit facing away to focus solely on voice. Mancuso stood on his head during the three-day recording session to compress his thorax and create disturbed sound.

The largely improvised calls feature multiple personalities, pig noises, crying, incoherent babbling. Clark himself also provided uncredited phone voices and portrayed Billy’s shadow. One reviewer stated: “I don’t think titans like Brando or Nicholson could have played them any better!”

Bob Clark as Billy’s Shadow (Uncredited): The director himself portrayed the killer’s shadow in several shots, using lighting techniques to make Billy appear different sizes and further confuse audiences about his identity.

Behind the Screams: Production

Development & Inspiration

The Origin Story

Canadian writer Roy Moore penned the original screenplay titled “Stop Me” (a chilling line Billy screams during the phone calls). The project was previously titled “The Babysitter” before producers Harvey Sherman and Richard Schouten hired Timothy Bond to rewrite Moore’s script, shifting the setting from a babysitter scenario to a university sorority house—a change that would prove crucial to the film’s impact.

Real Horror Inspired the Fiction

Black Christmas draws from multiple disturbing real-world sources:

- The urban legend “The Babysitter and the Man Upstairs” – Based on the unsolved 1950 murder of 13-year-old babysitter Janett Christman in Columbia, Missouri. The “calls from inside the house” concept originated from this tragic case.

- The Montreal Westmount Murders (1943) – A series of Christmas season murders perpetrated by a fourteen-year-old boy who bludgeoned family members to death.

- Real serial killers – George Webster and William Heirens (the “Lipstick Killer”) influenced characterization and phone call elements.

Bob Clark’s Revolutionary Vision

When Bob Clark came aboard as director and producer, he fundamentally reshaped the project. Clark felt Moore’s script was “too much of a straightforward slasher film” and made crucial alterations:

Character Depth: Clark rewrote dialogue throughout, wanting to capture the “astuteness” of young adults: “College students—even in 1974—are astute people. They’re not fools. It’s not all ‘bikinis, beach blankets, and bingo.’ College students had not been depicted with any sense of reality in American film.”

The Invisible Killer: Most significantly, Clark introduced the concept that the film would never show the killer to the audience. Moore initially “didn’t want to go along with” this approach but eventually agreed, creating one of the film’s most distinctive and influential features.

Dark Humor: Clark incorporated authentic comedy through Barb’s and Mrs. Mac’s drunkenness, basing Mrs. Mac on his own aunt.

The Title: Clark came up with the final title “Black Christmas,” stating he enjoyed “the irony of a dark event occurring during a festive holiday.” On Moore’s screenplay’s final page, Clark wrote a handwritten note: “a damn good script.”

Filming Details

Shooting Dates: March 25 to May 11, 1974 (6-7 weeks) Location: Toronto, Ontario, Canada

The Iconic Sorority House

The house at 6 Clarendon Crescent in South Hill, Toronto was discovered by Clark while location scouting. The homeowners agreed to lease it for production. The house still stands today as a private residence and has become a pilgrimage site for horror fans.

Additional Locations:

- University of Toronto – Soldiers’ Tower and Hart House on Hart House Crescent (where Mr. Harrison waits for Clare), Trinity College campus

- 97 Main Street at Swanwick Avenue – Old Toronto Police No. 10 station (now Community Centre 55)

- Grenadier Lake/Pond – Exterior search scenes

The Snow Problem

Surprisingly light snowfall during filming created the biggest production challenge. Most “snow” scenes outside the sorority house used foam material from the local fire department. Art director Karen Bromley meticulously preserved limited real snow, keeping people from walking through it to maintain pristine appearance—this became a running joke on set.

Production Challenges

Last-Minute Casting Changes:

- The Saxon/O’Brien Situation: Oscar-winner Edmond O’Brien was originally cast as Lt. Fuller, but when he arrived on set, his failing health from Alzheimer’s made the role impossible. John Saxon received an urgent call and traveled from New York to Toronto within two days.

- Gilda Radner’s Exit: Andrea Martin replaced Saturday Night Live-bound Gilda Radner just weeks before filming, requiring rapid integration.

Budget Constraints: The modest $686,000 CAD budget ($4.1 million today) forced creative practical solutions rather than expensive effects—limitations that actually enhanced the film’s atmospheric terror.

Technical Specifications:

- Format: 35mm

- Cameras: Panavision PSR R-200 with Panavision Standard Prime Lenses

- Aspect Ratio: Spherical 1.85:1

Special Effects Techniques

The Revolutionary POV Camera Rig

Camera operator Albert J. “Bert” Dunk invented a specialized body rig mounting the camera to his head/shoulder, keeping his hands free to act as the unseen killer. This innovation:

- Allowed him to physically climb the exterior trellis in the opening sequence

- Let him move naturally through the house while filming

- Enabled authentic interaction with objects and environments

- Predated Steadicam technology

The iconic shots—Clare’s suffocation, the trellis climbing, thrashing objects in the attic—all featured Dunk’s hands performing as the killer.

Practical Effects Philosophy

All effects were achieved practically for the limited budget:

- Clare’s suffocation: Real plastic bag with Griffin ripping a hole and stuffing it in her mouth, pencil holes for nose breathing

- Glass unicorn stabbing: Only raising motion shown with dried blood makeup

- Mrs. Mac’s hook attack: Practical prop on wire, cutting away before impact

- Shadow and silhouette effects: Strategic lighting placement by cinematographer Reginald Morris—no CGI, all practical

- Peter’s piano destruction: Keir Dullea physically attacking a real instrument in a single take

Multiple Killer Illusions

Clark used lighting techniques to “shape the shadows” and made Billy appear different sizes to confuse audiences. Multiple crew members’ hands were used for different shots. Clark himself portrayed the killer’s shadow uncredited.

Director’s Vision: Bob Clark’s Approach to Horror

Bob Clark (1939-2007) brought a unique sensibility to Black Christmas. Already known for horror with Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things (1972) and Deathdream (1974), Clark understood how to build atmosphere without resorting to cheap shocks.

Clark’s Horror Philosophy:

- Trust the audience’s imagination

- Build tension through what you DON’T show

- Treat characters as intelligent human beings

- Use humor to make horror more effective through contrast

- Never explain everything—ambiguity is terrifying

Clark would later demonstrate his range by directing the beloved family classic A Christmas Story (1983), making him perhaps the only director to create both the scariest and most heartwarming Christmas films in cinema history.

Tragic End: Bob Clark and his 22-year-old son Ariel were killed in a drunk driving accident on April 4, 2007, just before Black Christmas’s 2006 remake was released on home video. He served as executive producer on that remake.

Technical Mastery

Cinematography

Reginald H. Morris’s Visual Approach

Cinematographer Reginald Morris created Black Christmas’s distinctive look through:

Low-Key Lighting with High Contrast: Deep shadows and limited visibility make environments feel “oppressive and confining,” with “neatly planned lighting effects that evade more recent slasher movies.” Dark spaces force viewers “to imagine what threat might be lurking.”

Color Palette:

- Warm tones and dark wood in sorority house interior

- “Artificial glow of Christmas lights” providing eerie illumination

- Festive multicolored lights creating dissonance with dark events

- Snow-covered exteriors with vibrant Christmas lights creating stark contrast

- Clark photographed actors in “bright exuberant colors” while killer appears in “jaundiced, grainy colors”

Visual Style:

- “Moody wide-angle compositions”

- “Simplicity of production” and “stark and minimalistic approach”

- Faces framed in shadow, sinister silhouettes

- “Deliberately askew” frames during POV shots

- Split-diopter shots keeping foreground and background in focus

- Cross-cutting between violence and innocence

Framing Techniques:

- Multiple viewpoints of same scene (inside/outside house)

- Shots through windows showing Christmas lights

- Attic window framing Clare’s corpse throughout

- Frosted glass revealing killer’s shape

- Cracks in doors (the infamous eye shot)

- The cluttered attic creating “chaotic gallery of forgotten relics and latent menace”

The 2K restoration appears “film-like as you’re gonna get,” preserving Morris’s original intentions.

Camera Techniques

Revolutionary POV Cinematography

Black Christmas features “one of the earliest and most effective applications of first person cinematography,” predating and influencing Carpenter’s Halloween. Clark’s first-person stalking, achieved with a head-mounted rig, prefigures Halloween’s opening and helped normalize killer-POV language in slashers.

Bert Dunk’s Innovation:

- Custom body rig with head-mounted camera

- Shaky, handheld quality with uneven, disorienting perspective

- Heavy breathing serving as “auditory guide”

- Following “unseen intruder’s uneven rhythm”

Specific POV Moments:

- Opening trellis climbing

- Watching party through windows

- Stalking through house

- Lurking in attic

- Final sequences showing Billy still present

Psychological Effect: “Puts audience uncomfortably close to the villain,” emphasizing “voyeuristic nature” and making viewers unwilling accomplices. This “privileged insight into his presence creates sublime tension.”

Other Innovative Techniques:

Smooth Tracking Shots: Following characters through sorority corridors, creating fluid movement that contrasts with jarring POV.

“Patient Camera Moves (and Zooms!)” Including the phone exchange board sequence. Zooms watch victims through windows, “slowly zooming in further to see her better” as “he’s scanning for a victim.”

Handheld Shots: Clare’s death scene (raw, claustrophobic quality) and Jess’s fearful searching create immediate intimacy.

Static/Composed Shots: Clare’s corpse from multiple angles, bodies discovered, final pan from Jess to attic.

Innovative Framing:

- “Off-kilter frames, each shot deliberately askew”

- Extreme close-ups (eye in crack)

- Partial killer views (hands, eye, shadow)

Clark’s Storyboard Approach: The director drew meticulous storyboards for key shots, brought to set daily. John Saxon noted: “I could understand exactly what he needed, and the scene needed.”

Sound Design & Score

Carl Zittrer’s Experimental Score

Composer Carl Zittrer (later known for Porky’s and A Christmas Story) created one of horror cinema’s most unsettling scores using avant-garde “prepared piano” techniques:

The Process:

- Tied forks, combs, and knives onto piano strings to warp and distort sounds

- Recorded untuned piano at normal speed

- Played back at slower speeds creating increasingly disturbing effects

- Layered music directly onto 35mm film (never existed on separate tape)

The Lost and Found Score: Masters were thought lost for 40 years until Waxwork Records collaborated with Zittrer to track down originals in 2016, finally releasing them in 2021.

Musical Style: The score isn’t traditional notation but “musique concrète”—a sound-design suite mixing dialogue, effects, and source music from Billy’s perspective. Described as a “challenging listen” rewarding “avant-garde and experimental/industrial fans,” compared to Angel Heart and Eraserhead soundtracks.

Source Music:

- “Silent Night” ironically playing over opening credits

- “Jingle Bells”

- “O Come, All Ye Faithful” (during Barb’s murder)

- Choral effects by Counterpoint Singers conducted by Paul Feheley

Weaponizing Sound

Sound functions as a weapon—the “jarring soundscape” weaponizes everyday noises:

Organic Sounds Amplified:

- Victims’ “visceral screams pierce the air”

- Party noise drowning murder above

- “Brutal orchestrated stabbing” juxtaposed with “heavenly voices of children”

Killer’s Sounds:

- Heavy, labored breathing prominently featured—”guttural sounds, weary gasping” creating “primal, animalistic sound”

- Multiple voices during phone calls

- Pig noises, crying, incoherent babbling

The Telephone Bell: “Strident tone intensifies anxiety,” becoming trigger for Pavlovian dread. By film’s end, the ringing phone alone creates terror.

Use of Silence: Creates “bare soundscape when girls start disappearing”—”thick and suffocating” quiet in attic makes every sound noticeable. Contrast between party noise and isolated victims amplifies loneliness.

Dissonance:

- Christmas carolers singing during Barb’s murder (“angelic melodies” versus “brutality of attack”)

- Festive sounds corrupted by violence

- Phone calls interrupting holiday cheer

Ambient Atmosphere:

- Wind (especially in ending)

- Creaking house noises

- Muffled voices through walls

- Creating “chilly winter night” atmosphere

Special Effects

All practical effects serving story rather than spectacle:

Makeup Effects:

- Clare’s “death mask” expression in rocking chair

- Dried blood effects (minimal, strategically placed)

- Body positioning and rigor suggestions

Prop Effects:

- Plastic bag suffocation

- Glass unicorn weapon

- Crane hook (on wire, never shown impacting)

- Fire poker

Lighting as Effect:

- Shadows suggesting Billy’s presence

- Varying killer size through lighting tricks

- Single eye illuminated in door crack

- Attic window revealing corpse silhouette

Set Design Creating Atmosphere:

- Cluttered attic with authentic dust and cobwebs

- Sinister painted rocking horse

- Christmas decorations becoming ominous

- Multiple phone lines (crucial plot element)

Cultural Impact: Legacy of Innovation

Initial Reception and Box Office Context

Initial critical response was mixed. Variety called it “a bloody, senseless kill-for-kicks feature,” while A.H. Weiler of The New York Times questioned “why was it made.” Gene Siskel gave it 1.5/4 stars as a “routine shocker.” Kevin Thomas of Los Angeles Times proved more positive, calling it “a smart, stylish Canadian-made little horror picture.”

Modern critical re-evaluation shows dramatic reassessment. Rotten Tomatoes now scores it 71% fresh (as of time of writing) with critics consensus praising “the rare slasher with enough intelligence to wind up the tension.” Metacritic’s 65/100 (as of time of writing) indicates “generally favorable reviews.” TV Guide awards 3/4 stars praising Clark’s “skillful handling.”

Box office performance tells a story of initial disappointment becoming cult triumph. Strong Canadian performance ($1.3 million, third-highest-grossing Canadian film domestically) contrasted with US underperformance. Warner Bros. expected $7 million but initial December 1974 release earned only $284,345, overshadowed by The Godfather Part II and The Man with the Golden Gun. August 1975 Los Angeles re-release added $86,340 in one week. Expanded to 70 theaters for Halloween 1975, averaging only $700 per theater per day caused 58 locations to cancel. The film ended theatrical run December 1975 with less than $1 million additional US gross. Worldwide total of $4,053,000 made it profitable, with true success coming through home video and cult following.

Controversy, Censorship, and the Ted Bundy Incident

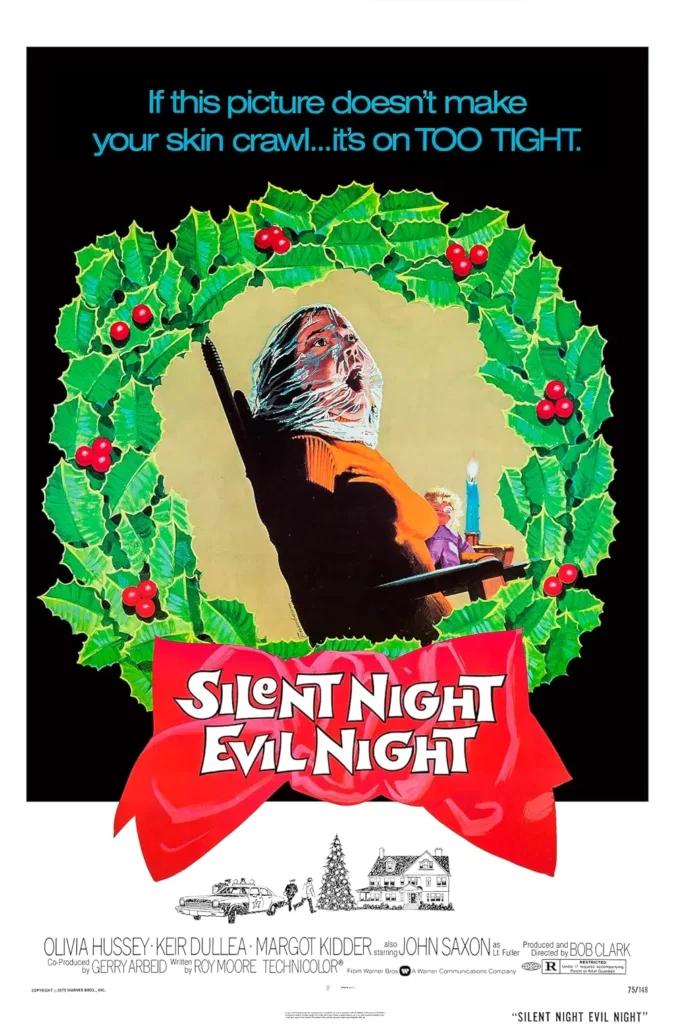

Title Changes reflected marketing confusion. Canadian release used “Black Christmas.” US theatrical changed to “Silent Night, Evil Night” due to fears audiences would mistake it for blaxploitation film. Later restored to “Black Christmas” for subsequent screenings. TV broadcasts used “Stranger in the House.”

Content Censorship saw BBFC (UK) remove the c-word and crude/sexual references from first obscene phone call. Warner Bros. demanded Clark change the ambiguous ending to show Chris revealing himself as killer before killing Jess—Clark refused, preserving the film’s power.

The Ted Bundy NBC Controversy represents the most significant censorship incident. Scheduled for NBC premiere January 28, 1978 as “Stranger in the House,” the broadcast faced crisis two weeks prior when Ted Bundy murdered two Chi Omega sorority sisters at Florida State University on January 15, 1978 (attacking two others as well). Florida Governor Reubin Askew contacted NBC President Robert Mullholland requesting the eerily similar film not be shown. NBC gave affiliates in Florida, Georgia, and Alabama the option to show “Doc Savage: The Man of Bronze” instead. The film eventually aired as late-night movie May 14, 1978.

Influence on Halloween and the Slasher Explosion

Direct Halloween connection remains widely acknowledged though exact details are debated. Bob Clark reportedly met with John Carpenter and discussed a potential Black Christmas sequel. Clark revealed his concept: the killer would be apprehended, then escape from psychiatric facility and return the following Halloween. This conversation allegedly influenced Carpenter’s Halloween, though the exact nature remains somewhat disputed.

Both films share similar POV shots and structure including holiday setting, unseen killer, suburban/campus setting. Halloween essentially refined and perfected the template Clark established, becoming one of the most influential horror films ever made.

Revolutionary Tropes and Techniques Black Christmas Pioneered

Black Christmas is recognized as one of the earliest and defining proto-slashers, alongside Mario Bava’s Bay of Blood (1971) and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974). While earlier films like Silent Night, Bloody Night (1972) also featured holiday horror elements, Black Christmas codified several slasher conventions and served as a crucial bridge between Italian giallo and the American slasher boom of the late 1970s and 1980s.

1. POV Killer Shots: Opening sequence showing killer’s perspective climbing into sorority house was revolutionary. Bert Dunk’s head-mounted camera rig predated Steadicam, becoming slasher standard. Influenced Halloween, Friday the 13th, countless others.

2. The Final Girl Trope: Jess Bradford is considered a formative early final girl—ranked #1 on Paste Magazine’s “20 Best Final Girls in Horror Movie History.” Unlike later iterations, Jess is sexually active and planning abortion, making her more complex. Carol Clover’s seminal “Men, Women, and Chain Saws” framework analyzing Final Girls found Black Christmas exemplified many observations, though Clover’s work came later.

3. “The Call Is Coming From Inside the House”: Based on urban legend, this became one of horror’s most iconic tropes. Influenced When a Stranger Calls (1979) and countless others.

4. Holiday Horror Template: A seminal holiday-set horror feature, spawning Halloween, My Bloody Valentine, New Year’s Evil, April Fool’s Day, entire subgenre.

5. Ambiguous Killer Identity: Never revealing killer’s face or backstory became influential template for creating existential dread. Contrast with remakes providing detailed backstories shows explanation diminishes terror.

6. Phone as Weapon: Obscene phone calls as psychological torture influenced When a Stranger Calls, Scream, countless thrillers.

7. Home Invasion Horror: Killer hiding inside house throughout—not breaking in but already there—represented embedded male threat.

8. Voyeuristic Eye Through Crack: The singular eye peering became visual shorthand for stalking.

9. Characters Picked Off One by One: While killer remains in attic, establishing slasher pattern.

10. Police Incompetence: Authorities dismissing women’s concerns reflected real institutional failures, became genre staple.

Genre Impact and Recognition

Black Christmas ranks on multiple “greatest horror films” lists: #87 on Bravo’s 100 Scariest Movie Moments; #67 in IndieWire’s 100 Best Horror Movies; #48 in Thrillist’s 75 Best Horror Movies; #23 in Esquire’s 50 Best Horror Films; #2 best slasher (Complex magazine, 2017); #3 best slasher (Paste magazine, 2018).

Often cited as one of the first true slasher films alongside Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) and Bay of Blood (1971), it established the “sorority horror” subgenre (House on Sorority Row, Slumber Party Massacre, Sorority Row). Influenced entire slasher cycle: Friday the 13th, Prom Night, Terror Train, When a Stranger Calls. Film scholars recognize it as “proto-slasher” bridging Italian giallo and American slasher, with John Saxon’s casting (star of first giallo The Girl Who Knew Too Much, 1963) creating deliberate connection.

Cult status development progressed through stages. 1970s-1980s saw initial obscurity outside Canada with cult reputation building through word-of-mouth and late-night TV. 1990s-2000s home video releases (VHS, DVD) introduced new generations. DVD special editions (2001, 2002, 2006) with extensive documentaries established historical importance. The 2006 remake paradoxically brought attention to superior original. 2008 Blu-ray cemented status. 50th anniversary theatrical re-release (December 2024) in 4K from original camera negative demonstrated enduring power.

Themes & Subtext

What It’s Really About

Reproductive Rights and Female Autonomy

The abortion subplot isn’t incidental—it’s central to the film’s feminist critique. Released just one year after Roe v. Wade (1973), Black Christmas engaged with contemporary battles over reproductive freedom.

Jess’s unwavering decision to have an abortion despite Peter’s threats and manipulation represents bodily agency in its purest form. Critically, the film never portrays her choice as morally wrong or deserving of punishment—a stark departure from typical horror conventions that punish sexually active women.

The film addresses:

- Reproductive freedom as fundamental right

- Sexual autonomy without punishment

- Economic independence (Jess’s career ambitions)

- Male violence as systemic issue

- Institutional indifference to women’s safety

Contemporary critics note the film’s prescience regarding ongoing attacks on reproductive rights and #MeToo era discussions of rape culture. The 2019 remake explicitly addressed these themes, demonstrating the original’s enduring relevance.

Toxic Masculinity and Male Violence

Black Christmas presents a spectrum of male toxicity:

Peter represents controlling, manipulative masculinity—gaslighting Jess, threatening her autonomy, becoming violent when she refuses to submit. His language mirrors pro-life rhetoric, equating abortion with murder. He demands marriage and motherhood, dismissing Jess’s career dreams.

Billy represents extreme, psychotic male violence existing outside patriarchal norms but stemming from the same entitlement. His mystery makes him “Every Man”—he could be anyone, anywhere, emphasizing the pervasive threat.

Critically, Peter’s death doesn’t solve the problem—Billy remains. This suggests male violence is systemic rather than individual. The nihilistic conclusion refuses catharsis, denying audience relief while mirroring how real violence against women offers no satisfying resolution.

Institutional Failure and Casual Misogyny

Police consistently dismiss women’s concerns, only taking action when men (Clare’s father, Peter) demand it. This reflects broader societal indifference to violence against women.

The final incompetence—leaving a traumatized woman sedated and alone without properly searching the house—represents catastrophic institutional failure with fatal consequences. This isn’t individual officer failure but systemic design—institutions supposed to protect women instead fail them completely.

Violation of Domestic Sanctuary

The sorority house represents female community and safety—a space where women can exist without male oversight. Billy’s presence in the attic, literally above and overlooking women’s private spaces, violates this sanctuary.

The “calls from inside the house” motif transforms home from haven to trap. Billy doesn’t break in—he’s already there, suggesting male violence isn’t an external threat but already embedded in women’s lives and spaces. His literal position above women symbolizes patriarchal power structures.

Symbolism

The Attic:

- Forgotten Past: Toys and relics suggest Billy’s traumatic childhood

- Male Dominance: Billy’s position above women symbolizes patriarchal power literally overlooking and controlling

- Hidden Danger: Violence against women going unnoticed by authorities

- Death Chamber: Grotesque tableaux as monuments to pathology

Clare’s Corpse in Rocking Chair:

- Enforced Motherhood: Positioning with baby doll suggests Billy punishes women not conforming to maternal roles

- Maternal Fixation: Rocking motion evokes motherhood, connecting to Billy’s obsession with “Agnes” and “the baby”

- Perpetual Presence: Clare remains visible through window throughout—unnoticed corpse symbolizes how violence against women becomes normalized/invisible

Christmas Lights and Holiday Setting:

- Juxtaposition: Cheerful setting against horrific violence emphasizes nihilism

- False Comfort: Christmas represents safety and joy, making violation more disturbing

- Giallo Influence: “Diffuse glow” creates beautiful but eerie atmosphere

- Inky Midwinter: Oppressive, claustrophobic mood

The Telephone:

- Male Intrusion: Billy’s voice invades feminine space through telecommunications

- Sexual Harassment: Obscene calls represent everyday harassment women endure

- Technology’s Dark Side: Phone connects and isolates simultaneously

- Final Ringing: Unanswered phone symbolizes continued threat and communication breakdown

The Unicorn Figurine:

- Ironic Purity: Symbol of virginity becomes murder weapon, subverting traditional associations

- Punishing Sexuality: Kills Barb, most sexually liberated character (though film doesn’t endorse this “punishment”)

The Eye:

- Male Gaze: Single glimpse represents voyeuristic male perspective

- Fragmented Identity: Seeing only parts emphasizes unknowability

- Surveillance: Eye watching through crack symbolizes constant observation and threat

Multiple Interpretations

Billy’s Identity (Deliberate Ambiguity):

- Escaped Mental Patient: References to institutionalization in phone calls

- Abused Child Grown Up: “Agnes” and “the baby” suggest childhood trauma

- Embodiment of Male Violence: Abstract threat rather than individual

- Supernatural Presence: Some interpret as not entirely human

- Multiple Personalities: Different voices suggest dissociative disorder

The film’s genius is refusing to confirm any interpretation. Explanation would diminish terror—Billy represents the unknowable, inexplicable violence women face.

The Ending (Three Valid Readings):

- Jess Dies: Most likely—Billy kills her off-screen

- Jess Survives: Traumatized but alive, Billy moves on to new victims

- Eternal Loop: Billy continues killing indefinitely—violence has no end

Peter’s Role:

- Red Herring: Innocent but suspicious boyfriend

- Accomplice/Inspired by Billy: Unconsciously influenced

- Symbolic Twin: Represents “respectable” male control vs. Billy’s chaos

- Tragic Victim: Misunderstood, killed by mistake

The film supports multiple readings without confirming any, creating productive ambiguity that fuels continued discussion 50 years later.

Franchise Context

Black Christmas (2006)

Director: Glen Morgan Released: December 25, 2006 by Dimension Films Box Office: $21.5 million worldwide Cast: Katie Cassidy, Mary Elizabeth Winstead, Michelle Trachtenberg, Lacey Chabert, Crystal Lowe, Andrea Martin (returning from 1974 film in different role)

Key Differences from Original:

- Provides extensive backstory for Billy (yellow jaundice, abusive family, incest, cannibalism)

- Introduces Billy’s sister Agnes as second killer

- Much more graphic gore and violence

- Removes all ambiguity, explaining everything

- Studio interference forced reshoots for more violence

Reception: Generally negative, considered inferior and unnecessarily explicit. Critics felt the detailed backstory undermined the original’s power—explaining Billy made him less terrifying.

Notable: Bob Clark served as executive producer before his tragic death in a drunk driving accident on April 4, 2007 (along with his son Ariel), just before the film’s home video release.

Legacy: While commercially successful, the remake is generally dismissed by fans and critics. It represents everything the original avoided—excessive explanation, gratuitous gore, lack of subtlety.

Black Christmas (2019)

Director: Sophia Takal Released: December 13, 2019 by Universal/Blumhouse Budget: ~$5 million Box Office: $18.7 million worldwide Cast: Imogen Poots, Aleyse Shannon, Lily Donoghue, Brittany O’Grady, Cary Elwes

Key Differences from Original:

- Completely new story keeping only sorority house Christmas setting

- Explicitly feminist, addressing toxic masculinity and rape culture

- Multiple killers controlled by supernatural bust of college founder

- PG-13 rating—less graphic than original

- More social commentary than horror

Reception: Mixed—praised for feminist themes, criticized for weak horror elements. Some appreciated the modern update of feminist themes, others felt it sacrificed scares for messaging.

Significance: Demonstrates the original’s themes remain relevant, though execution was controversial. The PG-13 rating particularly disappointed horror fans expecting genuine scares.

Other Franchise Materials

Fan Films:

- “It’s Me, Billy” (2021) – Unofficial sequel following Jess’s granddaughter 50 years later

- “It’s Me, Billy Chapter 2” (2024) – Released on original’s 50th anniversary

Cancelled Projects:

- After 2006 remake, a direct sequel to 1974 film was planned focusing on Olivia Hussey’s character Jess Bradford decades later. The project was scrapped after Bob Clark’s death.

Timeline Placement

The three films share only basic premise—there is no continuity between them. Each exists in its own universe:

- Black Christmas (1974) – Original timeline, ambiguous ending

- Black Christmas (2006) – Complete reboot with different backstory

- Black Christmas (2019) – Another complete reboot with supernatural elements

Quality Comparison

Critical Consensus: The 1974 original remains far superior to both remakes. The 2006 version is considered a failure that misunderstood the source material. The 2019 version has defenders for its feminist themes but is generally seen as missing the mark on delivering genuine horror.

The remakes demonstrate a key lesson: what makes Black Christmas terrifying is precisely what you DON’T show and DON’T explain. Both remakes tried to improve upon the original by adding backstory and clarity—and both proved that the ambiguity and restraint were the original’s greatest strengths.

Watch Guide

Best Viewing Experience

Recommended Setting: Dark room at night. Turn off all lights except perhaps a string of Christmas lights for appropriate ambiance. Close curtains/blinds—you don’t want to be looking at dark windows while watching.

Watch With: This depends on your horror tolerance:

- First-time horror viewers: Watch with a friend for support

- Seasoned horror fans: Alone enhances isolation and dread

- Film students/critics: With others for post-viewing discussion

Time of Day: Night is essential. The film’s power comes from shadows, darkness, and that creeping sense of vulnerability that only exists after sunset. Watching during daylight diminishes impact significantly.

Preparation Level:

- Come prepared for slow-burn atmospheric horror, not constant jump scares

- Understand this is from 1974—pacing and style differ from modern horror

- Be ready for obscene language and psychological intensity

- The ending will leave you unsettled—that’s intentional

Audio Setup: Good speakers or headphones are crucial. The sound design—breathing, footsteps, telephone rings, Carl Zittrer’s prepared piano score—is as important as the visuals.

Content Warnings

Language: Extremely crude sexual language during phone calls (c-word, graphic sexual descriptions), strong profanity throughout, misogynistic slurs

Violence: Woman suffocated with plastic bag, woman stabbed multiple times with glass unicorn, man’s throat slashed, woman killed with crane hook, person impaled with fire poker. Violence mostly implied/off-screen. Moderate blood, not excessive by modern standards. Corpses displayed in attic.

Sexual Content: Graphic sexual language during obscene phone calls, discussion of abortion (major plot point), implied sexual activity, brief male rear nudity on poster (comedic), references to sexual activity

Psychological Content: Intense stalking and voyeurism throughout, domestic abuse (Peter’s controlling behavior), mental illness portrayed through killer’s multiple personalities, implied child abuse in killer’s past, police dismissiveness toward women’s safety, unresolved ending may be disturbing

Substance Use: Heavy alcohol consumption by multiple characters, drunkenness played for both comedy and drama

Triggers:

- Pregnancy/abortion discussion

- Controlling/abusive relationship dynamics

- Sexual harassment via phone

- Institutional dismissal of women’s concerns

- Claustrophobia

- Being watched/stalked

Who Should Watch

Perfect For:

- Fans of Halloween, When a Stranger Calls, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre

- Those who enjoy atmospheric slow-burn horror over gore

- Horror historians wanting to see where slasher genre began

- Fans of intelligent, character-driven horror

- Viewers interested in feminist horror

- People who appreciate 70s filmmaking aesthetic

- Holiday horror enthusiasts looking beyond typical Christmas movies

Skip If:

- You need constant action and high body counts

- Modern pacing and editing are essential

- You want explicit gore and graphic violence

- You need all questions answered and backstory explained

- Slow-building tension frustrates you

- You’re sensitive to crude sexual language

- You require tidy, resolved endings

- You’re looking for a fun, lighthearted holiday watch

Preparation Tips

- Research the era: Understanding 1974 context (post-Roe v. Wade, second-wave feminism) enriches viewing

- Watch with appropriate expectations: This isn’t Friday the 13th—it’s psychological horror

- Pay attention to sound: The audio design is crucial to the experience

- Notice the craft: Watch for innovative camera work, especially POV shots

- Embrace ambiguity: The film deliberately leaves questions unanswered

The Verdict

Strengths

Atmosphere and Tension: Masterful use of silence and sparse sound design creating isolation. Juxtaposition of Christmas imagery with horror (carolers, decorations, “Silent Night”). Slow-burn pacing that pays off. Carl Zittrer’s prepared piano score creating unsettling soundscape.

Technical Innovation: Revolutionary POV cinematography predating Halloween. Creative use of shadows rather than showing killer. Clever editing and cross-cutting. Split-diopter shots creating depth and unease. Gripping phone trace sequence.

Character Development: Unusually strong for horror—well-developed characters with natural dialogue. Female characters treated as real people, not stereotypes. Complex protagonist dealing with real issues (pregnancy, abortion, controlling boyfriend).

Performances: Margot Kidder stealing scenes as sardonic Barb. Olivia Hussey bringing vulnerability and strength. John Saxon solid as competent cop. Marian Waldman delightful as alcoholic housemother. Nick Mancuso’s genuinely disturbing voice work.

Progressive Themes: Openly discussing abortion without judgment. Showing casual misogyny and police dismissiveness. Maintaining female protagonist’s bodily autonomy. Not punishing sexually active characters. Addressing relationship abuse.

The Mystery: Ambiguous ending remaining unsettling decades later. Never revealing killer creating lasting dread. Unanswered questions strengthening rather than weakening film. Resisting studio pressure for easy answers.

Restraint: Most violence off-screen. Relying on psychological horror over gore. Trusting audience’s imagination. Not overstaying welcome at 98 minutes.

Weaknesses

Pacing Issues: Middle section can lag for modern audiences. Procedural police work scenes drag. Takes time to reach horror for those expecting immediate scares.

Dated Elements: Some 70s humor doesn’t land. Fashion and hairstyles potentially distracting. Certain sexual assault jokes aged poorly (Barb’s “townies can’t get raped” line). Some theatrical rather than naturalistic acting.

Limited Character Development: Several sorority sisters barely characterized before death. Clare disappears almost immediately, limiting investment. Some supporting characters feel like cannon fodder.

The Ending: Frustrates viewers wanting resolution. Peter’s role remains confusing (involved or just suspicious?). Some plot threads feel unresolved (not deliberately ambiguous, just incomplete).

Technical Limitations: Low budget occasionally showing. Some scenes poorly lit (though creating atmosphere). Limited locations. Grainy film stock (though adding aesthetic for some).

Uneven Tone: Shifting between dark comedy and genuine horror can jar. Mrs. Mac’s alcoholism played for laughs while Barb’s is darker. Some humor undercuts tension.

Logic Issues: Why nobody checks attic during searches. How killer got bodies up there unnoticed. Some character decisions defy common sense (staying alone, not leaving house).

Final Thoughts

Black Christmas (1974) transcends proto-slasher origins to offer sophisticated commentary on gender, power, and violence that remains unsettlingly relevant 50 years later. Its refusal to provide easy answers or comfortable conclusions creates perpetual unease—the ambiguous ending where Billy survives in the attic while Jess’s fate remains uncertain denies catharsis, forcing viewers to sit with discomfort that mirrors how real violence against women offers no satisfying resolution.

The film’s technical innovations—Bert Dunk’s revolutionary POV camera rig, Carl Zittrer’s experimental prepared piano score, Reginald Morris’s atmospheric cinematography—established visual and sonic vocabulary that defined horror for decades. Its feminist themes addressing reproductive rights, bodily autonomy, institutional dismissiveness toward women’s safety, and toxic masculinity were groundbreaking for 1974 and remain prescient today.

What makes Black Christmas endure isn’t nostalgia or historical importance alone—it’s genuinely terrifying because it taps into primal fears transcending era or special effects. The violation of safe spaces, anonymous threats, being watched without knowing, male violence as systemic phenomenon—these remain as frightening today as in 1974.

As horror continues evolving, Black Christmas stands as reminder that atmosphere, intelligence, and restraint often terrify more effectively than gore or exposition. Fifty years and two remakes later, the original’s power remains undiminished—a testament to Bob Clark’s vision and the enduring appeal of horror that trusts audiences’ intelligence and respects their fears.

CreepyCinema Score: 9/10 – A masterpiece of atmospheric horror that codified the slasher genre and remains one of the scariest films ever made.

Easter Eggs & Hidden Details

Things You’ll Notice on Rewatches:

- Clare in the Window: Throughout the film, if you look carefully at exterior shots of the sorority house, you can glimpse Clare’s corpse positioned in the attic window rocking chair. Most characters (and viewers) miss this completely on first watch.

- Billy’s Timing: Billy only makes phone calls AFTER killing someone. The first call follows the murder of the high school girl in the park, subsequent calls follow each sorority sister’s death. The ringing phone at the end implies he’s killed the guard.

- The Sorority Name: Outside displays show “Pi Kappa Sigma” but a picture inside the house shows “Pi Beta Phi”—a continuity error that became an in-joke among fans.

- Multiple Voices in Phone Calls: Listen carefully to Billy’s calls—you can distinguish at least 3-4 different voice personalities, suggesting severe dissociative disorder or multiple people (though it’s one actor plus uncredited voices).

- Agnes References: Billy repeatedly mentions “Agnes” and “the baby” during phone calls, hinting at traumatic backstory deliberately never explained. Fans have debated for 50 years who Agnes was—mother? Sister? Victim?

- Shadow Tricks: Watch Billy’s shadow in different scenes—Bob Clark used lighting to make the killer appear different sizes, further obscuring his identity and confusing viewers about whether it’s always the same person.

- The Eye Color: In the door crack scene, the eye appears reddish—possibly suggesting Billy has been crying, or perhaps yellow jaundice (which the 2006 remake ran with).

- Mrs. Mac’s Hidden Bottles: Throughout the film, you can spot alcohol bottles hidden in creative places around the house if you look carefully—behind books, in plant pots, etc.

- Christmas Carol Irony: Every Christmas carol or holiday song in the film occurs during or immediately before violence, subverting their joyful associations.

- Peter’s Piano Music: The classical piece Peter attempts (and fails) at his audition is complex and demanding, suggesting his skill level doesn’t match his ambitions—mirroring his relationship expectations with Jess.

- The Unicorn’s Symbolism: The glass unicorn that kills Barb sits on her nightstand throughout earlier scenes—you can spot it in the background, foreshadowing its role.

- Telephone Trace Technology: The phone-tracing equipment shown was cutting-edge 1974 technology, lending authenticity. Modern viewers might not realize how revolutionary that tech was.

- Real Location: The sorority house at 6 Clarendon Crescent still exists and looks remarkably similar 50 years later. Horror fans make pilgrimages there despite it being a private residence.

Trivia & Fun Facts

Behind-the-Scenes Stories:

Bob Clark’s Double Christmas Legacy: Directed both Black Christmas (1974) and A Christmas Story (1983)—arguably cinema’s scariest and most beloved Christmas films respectively. The irony delighted Clark.

The Psychic Was Right: Olivia Hussey signed on after her psychic told her she would “make a film in Canada that would earn a great deal of money.” The psychic was correct—it became a cult classic earning millions over decades.

Steve Martin Superfan: When Hussey met Steve Martin in 1986, Martin revealed he’d seen Black Christmas 27 times and called it “one of my all-time favorite films.” Hussey assumed he meant Romeo and Juliet—Martin specified Black Christmas.

Standing on His Head for Art: Nick Mancuso stood on his head during three-day recording session to compress his thorax and create Billy’s disturbed voice—one of horror cinema’s most unusual performance methods.

The Bette Davis Role: Legendary actress Bette Davis was offered Mrs. Mac but declined. Marian Waldman’s performance proved perfect, though a Davis version would have been fascinating.

Malcolm McDowell Almost Played Peter: If Malcolm McDowell had accepted instead of Keir Dullea, Peter would have seemed far more obviously suspicious given McDowell’s A Clockwork Orange intensity.

Gilda Radner’s Career Choice: Saturday Night Live icon Gilda Radner was originally cast as Phyl but left for SNL one month before filming. Andrea Martin replaced her and later became SCTV legend herself.

Real Closet, Real Terror: Lynne Griffin’s suffocation scene was shot in an actual tiny closet, not a set piece, making the confined space authentically claustrophobic. Griffin poked nose holes in the bag and used swimming skills to hold her breath.

The Lost Score Found: Carl Zittrer’s experimental score was thought lost for 40 years (music was layered directly onto film, no tape masters). Waxwork Records finally tracked down originals in 2016, releasing them in 2021.

John Saxon’s Two-Day Turnaround: Saxon flew from New York to Toronto within two days after Edmond O’Brien’s health made the role impossible. Despite rushed preparation, Saxon’s performance anchors the film.

Multiple Killer Hands: Different crew members’ hands portrayed Billy in different shots. Bob Clark himself portrayed the killer’s shadow uncredited.

The Snow Problem: Surprisingly light snowfall forced production to use foam from fire department for most “snow” scenes. Art director Karen Bromley’s preservation of real snow became a running on-set joke.

Forks, Combs, and Knives: Carl Zittrer created the unsettling score by tying household objects to piano strings—forks, combs, knives—warping the sound. He recorded at normal speed, then played back slower for increasingly disturbing effects.

The Title Changes: Film was called “Stop Me” (script), “The Babysitter” (early draft), “Black Christmas” (Canadian release), “Silent Night, Evil Night” (US theatrical—WB feared blaxploitation confusion), and “Stranger in the House” (TV).

Where to Watch (As of October 2025)

Subscription streaming: Shudder (horror-specific service), AMC+, Peacock Premium and Premium Plus, Amazon Prime Video (with ads or subscription), Philo, Fandor (standalone and Amazon Channel), Screambox (standalone and Amazon Channel), Night Flight Plus, Midnight Pulp, Shout! Factory TV (free with ads).

Free streaming (ad-supported): Tubi, Pluto TV, The Roku Channel, Amazon Freevee, Plex, Kanopy (free with library card), Fawesome.

Rental/purchase: Amazon Video, Apple TV/iTunes, Fandango at Home/Vudu, Microsoft Store.

Physical media: 4K Ultra HD + Blu-ray: Scream Factory Collector’s Edition (December 6, 2022)—most comprehensive release. Blu-ray: Multiple editions including Anchor Bay “Season’s Grievings Edition” (2015), Scream Factory (2016). DVD: Critical Mass Special Edition (2006), various editions. Available at Barnes & Noble and other retailers.

Theatrical: 50th Anniversary 4K restoration played select theaters December 2024.

Note: Streaming availability changes frequently. Check JustWatch.com for current platform availability.

Conclusion: Enduring Power of Ambiguity

Black Christmas transcends proto-slasher origins to offer sophisticated commentary on gender, power, and violence that remains unsettlingly relevant 50 years later. Its refusal to provide easy answers or comfortable conclusions creates perpetual unease—the ambiguous ending where Billy survives in the attic while Jess’s fate remains uncertain denies catharsis, forcing viewers to sit with discomfort that mirrors how real violence against women offers no satisfying resolution.

The film’s technical innovations—Bert Dunk’s revolutionary POV camera rig, Carl Zittrer’s experimental prepared piano score, Reginald Morris’s atmospheric cinematography—established visual and sonic vocabulary that defined horror for decades. Its feminist themes addressing reproductive rights, bodily autonomy, institutional dismissiveness toward women’s safety, and toxic masculinity were groundbreaking for 1974 and remain prescient regarding ongoing battles over abortion rights and #MeToo era discussions of rape culture.

What makes Black Christmas endure isn’t nostalgia or historical importance alone—it’s genuinely terrifying because it taps into primal fears transcending era or special effects technology. The violation of safe spaces, anonymous threats, being watched without knowing, male violence as systemic rather than individual phenomenon—these remain as frightening today as in 1974. The film’s greatest achievement may be making the familiar terrifying, transforming home, holiday, and institutional protection into sources of dread that reflect reality for many women where danger comes not from monsters but from systems and men they’re supposed to trust.

As horror continues evolving, Black Christmas stands as reminder that atmosphere, intelligence, and restraint often terrify more effectively than gore or exposition. Its influence ripples through Halloween, Friday the 13th, Scream, and countless others, yet it remains unique in its sophisticated approach and willingness to leave questions unanswered. Fifty years and two remakes later, the original’s power remains undiminished—a testament to Bob Clark’s vision, his cast and crew’s dedication, and the enduring appeal of horror that trusts audiences’ intelligence and respects their fears.