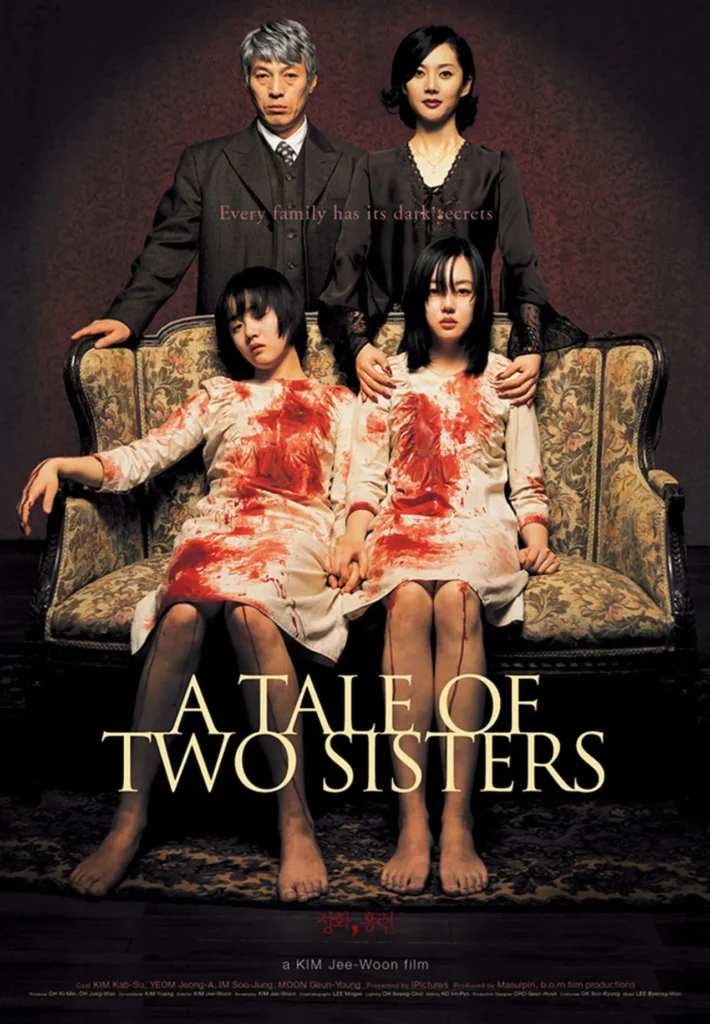

A Tale of Two Sisters rips through the fabric of reality like a razor through silk, leaving behind wounds that refuse to heal and questions that haunt long after the credits roll. Kim Jee-woon’s masterwork of psychological horror doesn’t just tell a story – it burrows into your psyche, making you question every shadow that moves across your bedroom wall, every creak of old wood in the dark of night.

The film opens like a music box wound too tight, its haunting melody already threatening to snap. We meet Su-mi, returning home to a pristine lakeside house with her younger sister Su-yeon after a stay in a mental institution. Their father, distant and wrapped in his own grief, has remarried to their stepmother Eun-joo – a woman whose pristine exterior masks something rotting underneath. From the first moment she appears on screen, every smile feels like a paper cut, every gentle word carries the weight of an incoming storm.

The house itself becomes a character, its traditional Korean architecture mixing with western furniture in a way that creates immediate unease. Everything is too perfect, too arranged, like a dollhouse waiting for someone to start moving the pieces. The camera glides through these spaces with predatory grace, lingering just long enough on empty corners and darkened doorways to make us wonder what might be lurking just beyond our sight.

Kim Jee-woon orchestrates every frame like a conductor leading a symphony of dread. Scenes build with excruciating patience, tension coiling tighter and tighter until you’re holding your breath without realizing it. A simple family dinner becomes psychological warfare. A bedroom at night transforms into a battlefield where reality itself seems to waver and bend. The director understands that true horror lives in the spaces between what we think we know and what we fear might be true.

Jung-ah Yum’s performance as the stepmother Eun-joo is a masterclass in controlled menace. She moves through the house like a snake in high heels, her every gesture calculated to maintain control while hinting at the chaos churning beneath. When she smiles, you can feel your skin crawl. When she speaks softly, you want to scream. It’s the kind of performance that makes you check the shadows behind you even when watching in broad daylight.

But it’s Su-mi, played with devastating complexity by Su-jeong Lim, who forms the cracking mirror at the center of this psychological maze. Her fierce protection of her younger sister, her barely contained rage at her stepmother, and her growing confusion as reality begins to splinter – all of it comes together in a performance that feels less like acting and more like watching someone’s soul slowly fracture in real time.

The film’s sound design deserves its own chapter in the annals of horror history. Every footstep, every creak of a door, every whisper in the dark is wielded like a weapon. Silence becomes suffocating. The score, when it appears, doesn’t simply accompany scenes – it wraps around your throat like ghostly fingers, tightening its grip with each new revelation.

As the story unfolds, the line between reality and delusion becomes increasingly blurred. What starts as a seemingly straightforward tale of family trauma and supernatural horror transforms into something far more complex and devastating. Kim Jee-woon plays with our perceptions like a cat toying with a mouse, leading us down corridors of uncertainty until we’re not sure what’s real and what’s imagined. The truth, when it finally emerges from the shadows, doesn’t clarify – it shatters.

The film’s exploration of grief, guilt, and family trauma cuts deeper than any ghost’s claws could reach. Every supernatural occurrence is rooted in very human pain, every haunting image tied to emotional wounds that refuse to heal. This isn’t just a story about things that go bump in the night – it’s about the monsters we create within ourselves, the ways we twist reality to protect ourselves from unbearable truths.

The cinematography by Lee Mo-gae transforms everyday spaces into landscapes of psychological horror. Shadows don’t just darken corners; they seem to breathe. Colors shift subtly throughout the film, with reds that feel like open wounds and blues that chill to the bone. Every frame is composed with painterly precision, creating a visual language that speaks directly to our deepest fears.

There’s a scene midway through the film where Su-mi confronts her stepmother in what begins as a battle of wills and evolves into something far more terrifying. The camera work here is a thing of terrible beauty, the way it circles the characters like a predator, the way it catches glimpses of impossible things in mirrors and doorways. It’s a sequence that makes you want to look away while making it impossible to do so.

The film’s structure itself becomes part of its horror. What seems at first like a linear narrative begins to fold in on itself like origami made of razor blades. Time becomes fluid, memories become unreliable, and reality itself seems to crack and splinter. The editing by Lee Hyeon-mi doesn’t just cut between scenes – it tears holes in the fabric of the story, leaving us to piece together the truth from the bleeding edges.

When the film’s final revelations come, they don’t arrive like thunderbolts of clarity – they seep in like poison, slowly corrupting everything we thought we knew. The truth about Su-mi, Su-yeon, and their stepmother is both more and less than what we’ve been led to believe. It’s a twist that doesn’t feel like a cheap trick but rather like a knife being slowly twisted in a wound we didn’t even know we had.

A Tale of Two Sisters isn’t just a milestone in Korean horror – it’s a masterpiece of psychological storytelling that transcends cultural and linguistic barriers to speak directly to our universal fears about family, identity, and the fragility of our own minds. It’s a film that understands that the most terrifying ghosts aren’t the ones that manifest in darkness, but the ones we carry within ourselves, born from guilt, grief, and the lies we tell ourselves to survive.

Nearly twenty years after its release, the film’s influence can be seen in countless other works, but none have quite managed to capture its perfect balance of psychological complexity and gut-wrenching horror. Its American remake, The Uninvited, while competent, feels like a pale shadow next to the raw emotional power of the original.

The film’s final moments leave us not with answers, but with wounds – beautiful, terrible wounds that refuse to heal cleanly. Like Su-mi, we’re left to question everything we’ve seen, everything we’ve believed. The true horror isn’t in what the film shows us, but in what it makes us realize about our own capacity for self-deception, about the stories we tell ourselves to avoid facing unbearable truths.

A Tale of Two Sisters isn’t just a horror film – it’s a descent into the darkest corners of the human psyche, a journey through the funhouse mirrors of trauma and denial, where every reflection shows us something we desperately wish we couldn’t see. It’s a masterpiece that doesn’t just frighten – it scars, it transforms, it lingers like a ghost in the corners of your mind, whispering truths you’d rather forget.

In the end, Kim Jee-woon has created something far more terrifying than a simple ghost story. He’s created a reflection of our own fractured relationships, our buried guilt, our desperate attempts to rewrite the past. A Tale of Two Sisters stands as a testament to horror’s ability to tell profound truths through the lens of the fantastic, to use the supernatural to illuminate the darkest corners of human nature. It’s a film that doesn’t just deserve to be watched – it demands to be experienced, to be felt, to be carried with you like a beautiful scar that never quite heals.