Introduction: A Revolutionary Blend of Science Fiction and Horror

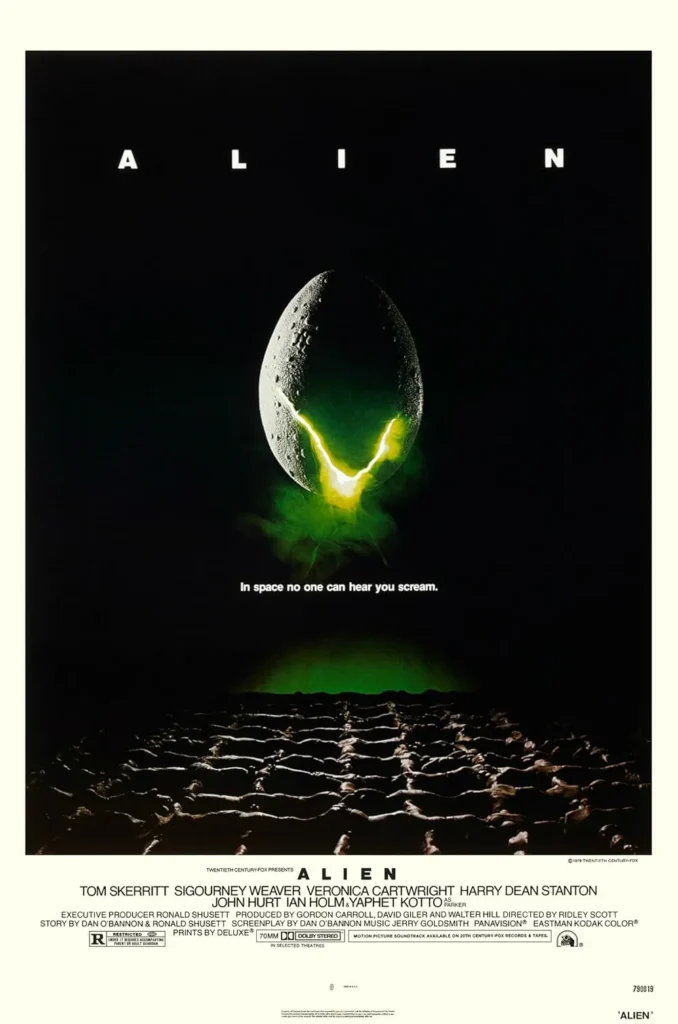

Ridley Scott’s Alien stands as one of the most influential films in cinema history. Released in 1979, this groundbreaking science fiction horror film introduced audiences to the terrifying Xenomorph (a term popularized in the 1986 sequel; not used in the 1979 film) and the iconic hero Ellen Ripley, played by Sigourney Weaver. With its haunting tagline “In space, no one can hear you scream,” Alien transformed the landscape of both horror and sci-fi genres forever.

What began as a production with a budget of about $11 million (reported range $8.4–14M) became a box office phenomenon, with first-run domestic earnings of $78.9 million, UK receipts of £7.9 million, and worldwide estimates ranging from $104–$188 million. The film won the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects and became a cultural touchstone that continues to influence filmmakers today.

This definitive guide explores every aspect of Alien’s creation, from Dan O’Bannon’s early screenplay to H.R. Giger’s nightmarish creature designs, from the shocking chestburster scene to the film’s lasting cultural legacy. Whether you’re a longtime fan or discovering this classic for the first time, this comprehensive resource will deepen your appreciation for one of cinema’s true masterpieces.

The Origins: How Alien Was Born

Dan O’Bannon’s Vision

The genesis of Alien began in the mid-1970s with screenwriter Dan O’Bannon. After co-writing the low-budget sci-fi comedy Dark Star (1974), O’Bannon imagined taking that film’s concept of an alien on a spaceship and transforming it into pure horror. He initially called his script “Memory,” which featured a space crew awakened from stasis by a mysterious signal on a distant planetoid.

The crucial turning point came in 1975 when O’Bannon joined Alejandro Jodorowsky’s ill-fated attempt to adapt Frank Herbert’s Dune. During six months in Paris, O’Bannon met three visionary artists who would profoundly influence Alien: H.R. Giger, Chris Foss, and Jean “Moebius” Giraud. Giger’s surreal, biomechanical artwork particularly captivated O’Bannon. He later recalled: “His paintings had a profound effect on me. I had never seen anything that was quite as horrible and at the same time as beautiful.”

Influences and Inspirations

O’Bannon freely admitted that Alien borrowed from numerous earlier works. “I didn’t steal Alien from anybody. I stole it from everybody!” he famously quipped. The film’s DNA includes:

It! The Terror from Beyond Space (1958): This B-movie about a deadly stowaway creature hunting a spaceship crew provided Alien’s core premise.

The Thing from Another World (1951): The paranoid claustrophobia of professionals being stalked by an alien in an isolated setting.

Forbidden Planet (1956): The concept of a crew ignoring warnings and being picked off one by one.

Planet of the Vampires (1965): Mario Bava’s Italian sci-fi film featured a scene strikingly similar to Alien’s Space Jockey discovery, with astronauts finding a derelict ship containing a giant fossilized alien pilot.

Literary Sources: Clifford D. Simak’s “Junkyard” (1953) inspired the egg chamber, while Philip José Farmer’s Strange Relations (1960) explored alien reproduction concepts. O’Bannon also cited gruesome EC Comics tales where monsters erupt from within people. Additionally, A.E. van Vogt’s Voyage of the Space Beagle contained thematic similarities that led van Vogt to sue Fox; the studio settled out of court.

The Breakthrough: Parasitic Impregnation

Working with his friend Ronald Shusett, O’Bannon struggled with how to get the alien creature onto the ship in an interesting way. The breakthrough came when Shusett had a eureka moment: “the alien screws one of them… jumps on his face and plants its seed!” This concept of parasitic impregnation, with an alien embryo later bursting from the chest, solved the story’s biggest problem and created the film’s most shocking sequence.

Shusett later revealed that O’Bannon’s personal experience with Crohn’s disease inspired the chestburster scene. O’Bannon’s internal pains gave him a horrifying understanding of what it might feel like to have something gnawing its way out from within.

From Script to Screen

Initially pitched to studios as “Jaws in space,” the Alien screenplay nearly went to low-budget producer Roger Corman. Instead, it reached Brandywine Productions (run by Gordon Carroll, David Giler, and Walter Hill) with backing from 20th Century Fox.

The producers felt the script needed work. Giler and Hill undertook substantial rewrites, most notably creating the character of Ash, the ship’s android science officer, which was entirely absent from O’Bannon’s original draft. While O’Bannon initially resisted this addition, he later acknowledged that the android subplot became “one of the best things in the movie.”

After the Writers Guild of America arbitrated the credits, Dan O’Bannon received sole screenwriting credit, with O’Bannon and Ronald Shusett sharing “Story by” credit.

The Star Wars Effect: How Alien Got Greenlit

Fox’s initial hesitation about financing another science fiction film evaporated after the massive success of Star Wars in 1977. Producer Gordon Carroll recalled: “When Star Wars came out and was the extraordinary hit that it was, suddenly science fiction became the hot genre.”

O’Bannon quipped that “the only spaceship script they had sitting on their desk was Alien.” Fox quickly greenlit the project in 1977 with an initial budget of around $4.2 million, which would eventually increase to about $11 million (reported range $8.4–14M).

Hiring Ridley Scott

The search for a director proved challenging. Walter Hill declined, uncomfortable with the heavy effects work. The producers considered Peter Yates, John Boorman, Jack Clayton, Robert Aldrich, and even Robert Altman, but worried they would give it a schlocky “B-monster movie” approach.

The solution came in the form of Ridley Scott, a rising British filmmaker whose debut feature The Duellists (1977) had won critical acclaim. Scott enthusiastically signed on and immediately drew meticulous storyboards for the entire film. His visual designs so impressed Fox executives that they increased the budget substantially, giving him more resources to realize his vision.

Scott famously described his vision for Alien as “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre of science fiction,” emphasizing the story’s horror elements over pure sci-fi adventure.

Pre-Production: Creating a Nightmare

H.R. Giger’s Biomechanical Horror

The film’s bold, nightmarish aesthetic came primarily from Swiss artist H.R. Giger. O’Bannon had shown Scott a Giger painting titled Necronom IV, which depicted a lanky, skeletal creature that became the basis for the creature design. Despite Fox’s initial concerns that Giger’s style was “too ghastly,” Scott persisted, even flying to Zürich to personally recruit him.

Giger was hired to design all aspects of the alien world:

- The creature in its various life stages

- The eggs and facehugger

- The derelict alien ship

- The giant fossilized pilot (Space Jockey)

His mandate was to make everything look truly alien through his signature biomechanical style, blending anatomical forms with industrial components. Giger built the life-size Space Jockey set by sculpting it from clay, incorporating real human and animal bones into the structure to create a ribbed, fossilized creature fused to its chair.

Actress Veronica Cartwright (Lambert) recalled Giger’s sets as intensely sexual: “so erotic… big vaginas and penises… like you’re going inside some sort of womb… sort of visceral.” This overt sexual and birth imagery was a deliberate motif designed to unconsciously disturb audiences.

Creature Design and Practical Effects

The Facehugger: Giger’s initial concepts went through several iterations before arriving at the spidery, hand-like parasite with a long tail. The final prop looked biological inside and out, with creative practical effects bringing it to life. When it tightens around Kane’s neck, the crew used animal intestines for the tail and pulled it tight for a realistic effect.

The Chestburster: The infamous birth scene required a spring-loaded mechanism built into a fake torso, with the small puppet (about 2 feet long) erupting through amid real animal organs. Director Ridley Scott insisted on using actual cow guts, clams, and freshly slaughtered animal parts for authenticity, explaining: “prosthetics weren’t that good… you can’t make better stuff than that. It’s organic.”

The Adult Creature: Giger’s masterpiece featured an elongated head, no visible eyes, a shiny black exoskeleton, and a whipping tail. He incorporated materials like snake vertebrae for the ribs and cooling tubes from a Rolls-Royce for mechanical texture. The creature’s transparent dome originally allowed glimpses of a human skull form inside, though this is barely visible in the final film. Italian effects maker Carlo Rambaldi built the spring-loaded inner jaws that shot out from the creature’s mouth to strike victims.

The full creature suit was worn by Bolaji Badejo, a 6’10” Nigerian design student whom the filmmakers discovered in a London pub. His extremely tall, thin frame gave the alien an otherworldly lankiness. Encased in Giger’s latex costume with an elongated skull headpiece, Badejo could barely see and had to move slowly and deliberately, which ironically enhanced the alien’s eerie, inhuman movement.

Human Technology and Set Design

While Giger handled all things alien, Ron Cobb and Chris Foss designed the human technology and environments. Cobb conceived the Nostromo as a utilitarian, industrial “truck in space,” with cramped corridors and clunky pipes everywhere emphasizing working-class realism.

French artist Moebius drew costume concepts that became the basis for the EVA spacesuits, which had an ornate, semi-gothic look while remaining functional.

Filming: 14 Weeks of Tension and Terror

Principal photography for Alien ran from July 5 to October 21, 1978, at Shepperton Studios and Pinewood Studios in England, with miniature photography conducted at Bray Studios. Over 200 crew members built the principal sets across these intense 14 weeks.

The Legendary Chestburster Scene

The practical effects climax required extreme measures to capture genuine terror from the cast. Actor John Hurt (Kane) was positioned under a dining table with only his head and arms showing, while a prosthetic torso packed with blood and viscera was attached to his body.

Ridley Scott deliberately shielded the full plan from the other actors. They knew generally that an alien would burst out but weren’t prepared for the level of gore. Multiple cameras were set up to capture the mayhem in one take.

When the creature finally exploded through Kane’s chest, a jet of blood hit Veronica Cartwright directly. She was so startled that she fell over and reportedly fainted as soon as Scott yelled cut. The actors’ horrified reactions on camera (Parker and Lambert screaming in panic) are completely genuine.

The set was draped in plastic sheets and crew wore raincoats in expectation of a bloodbath, which only increased the cast’s anxiety. As the fake alien puppet lunged out amid butcher’s offal, a moment of cinematic history was captured. Editor Terry Rawlings later said preview audiences in 1979 were screaming and even running out of the theater at this scene.

Scott’s Atmospheric Direction

Ridley Scott’s directing style was intensely atmospheric and detail-oriented. He shot with dim, moody lighting, lots of smoke or steam, and deliberately obscured views to keep the alien’s appearances fleeting.

For the exterior planet scenes, actors wearing big EVA suits struggled with heat and limited visibility, adding to the genuine sense of slow, laborious danger. In some shots, Scott’s own children wore scaled-down suits to force perspective and make the giant Space Jockey set look even larger.

A detailed 58-foot model of the Nostromo refinery was constructed for exterior shots. Scott employed an old-school method of shooting spaceship models at slow frame rates while moving the camera past them, which when played at normal speed gave a convincing sense of a huge ship gliding through space.

Post-Production and Music

Editor Terry Rawlings and Ridley Scott crafted a deliberate pace emphasizing suspense over action. The film takes nearly an hour before the first major death occurs, an unusual approach for a sci-fi thriller at the time.

Jerry Goldsmith composed an eerie, avant-garde soundtrack, though he famously clashed with Scott and Rawlings over music placement. Some cues Goldsmith composed were replaced with temp tracks the editors had grown attached to. The director used Howard Hanson’s Symphony No. 2 (“Romantic”) for the end credits and included cues from Goldsmith’s earlier score for Freud in several scenes. Despite Goldsmith’s disappointment, what remains greatly enhances the film, notably the haunting opening title music that perfectly sets the tone of looming dread.

Plot Summary: Terror in Deep Space

The Awakening

In deep space, the commercial towing starship USCSS Nostromo carries 20 million tons of mineral ore back to Earth. The crew of seven (Captain Dallas, Executive Officer Kane, Warrant Officer Ripley, Navigator Lambert, Engineers Parker and Brett, and Science Officer Ash) are in stasis as the journey is automated.

The crew is awakened partway home because “Mother,” the ship’s onboard AI, has intercepted a mysterious transmission from a nearby uncharted planetoid. Company policy requires investigating any potential signs of intelligent life. (In the film, characters refer only to “the Company,” though “Weylan-Yutani” is visible on computer monitors and props; the full “Weyland-Yutani” Corporation name becomes explicit in the 1986 sequel Aliens.)

The Derelict Discovery

Dallas, Kane, and Lambert head out in spacesuits to trace the signal source. Trekking across a windswept, foggy alien landscape, they find a gigantic derelict alien spacecraft. Inside, they discover the fossilized corpse of a huge alien pilot (the “Space Jockey”) with a burst hole in its chest.

Back on the Nostromo, Ripley decodes part of the transmission and realizes it was not a distress call but a warning. However, she cannot relay this in time to the away team.

The Parasite

Kane descends into a cavernous chamber beneath the derelict, discovering hundreds of large eggs. As he inspects one, it suddenly opens and a crab-like creature springs out, attaching itself to Kane’s face through his helmet.

Dallas and Lambert carry the unconscious Kane back to the airlock. Ripley, now in command on board, refuses to let them in, citing quarantine protocol. However, Science Officer Ash overrides Ripley’s orders and opens the hatch, bringing Kane and the creature inside.

In the infirmary, they try to remove the “facehugger,” but discover it has highly corrosive acidic blood. Eventually, the creature detaches on its own and is found dead. Kane wakes up, groggy but seemingly unharmed.

The Birth

During a final crew meal before returning to stasis, Kane suddenly chokes and convulses. In the now-legendary horror sequence, an infant alien creature bursts through Kane’s chest, killing him. The newborn alien screeches and flees into the depths of the ship.

Hunted One by One

Using motion trackers and improvised weapons, the crew spreads out through the Nostromo’s dark corridors. Engineer Brett follows the ship’s cat, Jones, into a maintenance room, where the now-fully-grown creature (over 7 feet tall) drops from above and kills him.

Captain Dallas enters the ventilation ducts with a flamethrower to flush the creature toward an airlock. In a tense crawl through the shafts, Dallas encounters the creature head-on, and it snatches him.

Ash’s Betrayal

Accessing Mother for advice, Ripley discovers a secret Company directive (Special Order 937): the Nostromo was redirected to retrieve this alien life form at all costs, with the note “crew expendable” as part of the order.

Ash tries to stop Ripley from revealing this. He attacks her with inhuman strength, and during the struggle it’s revealed that Ash is actually a synthetic android working to protect the alien. Parker and Lambert intervene, knocking Ash’s head loose. The disabled android admits he was assigned to ensure the organism’s survival, chillingly calling it “a perfect organism” and mocking the humans’ chances.

Final Confrontation

The remaining trio decides to self-destruct the Nostromo and escape in the small shuttle. Ripley initiates the sequence while Parker and Lambert gather supplies. The creature ambushes Parker and Lambert, brutally killing them both.

Now alone, Ripley activates the self-destruct, grabs Jones the cat, and races to the shuttle. She barely boards the Narcissus and launches away just as the Nostromo explodes in a nuclear fireball.

The Last Scare

As Ripley prepares for hypersleep in the shuttle, the creature has stowed away inside. Exhausted and terrified, she slowly dons a spacesuit, then uses the shuttle’s atmosphere vents to flush the creature out. When it emerges, she opens the airlock door, causing explosive decompression. The alien is sucked toward space, and she shoots it with a grappling hook. She then ignites the engines to blast the creature into space.

In the final scene, Ripley records a log entry as the sole survivor (“Last survivor of the Nostromo, signing off”) and, with Jones in a cryotube beside her, enters hypersleep for the long journey home.

Cast and Characters: Perfect Casting

Sigourney Weaver as Ellen Ripley

Ellen Ripley stands as one of cinema’s most iconic heroes. Originally written as a unisex character, Ripley was eventually cast as a woman when a studio executive reportedly asked, “Why can’t Ripley be a woman?” This proved a masterstroke.

Sigourney Weaver, then 28 and an unknown theater actress, imbued Ripley with natural authority and competence that grows throughout the film. She’s not introduced as a destined hero but emerges as the most pragmatic and tough-minded survivor. Ripley is never objectified (Weaver’s physique is covered in a baggy jumpsuit most of the film) and holds her own among men, ending up saving herself without needing a male rescuer.

This role was Weaver’s breakout, with one early review predicting she “should become a major star.” That prediction proved accurate as Weaver went on to lead three Alien sequels and earn multiple Oscar nominations.

The Ensemble Cast

Tom Skerritt as Dallas: The calm, level-headed captain who attempts to fulfill company orders. Skerritt initially declined the film when the budget was low, then joined once Scott was attached.

John Hurt as Kane: The ill-fated executive officer who becomes the host for the alien embryo. Hurt’s memorable performance made Kane’s death one of cinema’s most shocking scenes.

Ian Holm as Ash: The science officer secretly working for the Company. Holm portrays Ash with unsettling calm that flips to ruthless aggression once his android identity is exposed.

Veronica Cartwright as Lambert: The navigator who provides emotional contrast to Ripley’s decisiveness, expressing the audience’s terror.

Yaphet Kotto as Parker: The outspoken chief engineer who adds humor and groundedness until his valiant but futile attempt to save Lambert.

Harry Dean Stanton as Brett: Parker’s laconic partner, famous for his “Right!” catchphrase. He’s the first crew victim of the fully grown creature.

Casting Philosophy

Director Ridley Scott insisted on hiring strong, believable actors rather than typical genre archetypes. The production deliberately cast older actors than usual for a thriller. Most of Alien’s cast were in their 30s and 40s (Skerritt was 46, Holm 48, Stanton 53), giving the crew a seasoned, authentic working-class feel.

This was a deliberate contrast to the fresh-faced heroes of many sci-fi movies. The Nostromo crew comes off as ordinary people doing a job, which helped audiences invest in the characters and made their deaths more impactful.

Themes and Analysis: More Than Just a Monster Movie

The Perfect Organism: Nature’s Ultimate Killer

The film presents the creature as the ultimate predator, evolved (or engineered) for one purpose: to survive and propagate with absolutely no morality or emotion. Ash’s notorious description frames it as “its structural perfection is matched only by its hostility… unclouded by conscience, remorse, or delusions of morality.”

This plays into a theme of the uncaring cosmos. The creature is a force the crew cannot reason with or tame, only flee from or fight. As critic Roger Ebert noted, Alien basically boils down to “things that can jump out of the dark and kill you.” By situating that primal terror in a high-tech future, the film suggests that no matter how advanced humanity becomes, we are still vulnerable animals facing predators in the dark.

Body Horror and Sexual Violation

Alien is a landmark in the “body horror” subgenre. Much of the terror comes from physical violation. The facehugger’s attack and chestburster birth constitute a grotesque inversion of sexual and reproductive norms. The film essentially makes male characters victims in ways analogous to rape and forced pregnancy.

Film journalist David Edelstein observed that Alien “covered all possible avenues of anxiety” in the 1970s: “Men traveled through vulva-like openings, got forcibly impregnated, and died giving birth to rampaging gooey vaginas dentata.”

The iconic chestburster scene features Kane as the unwitting “male mother” who suffers a violent, fatal birth. This imagery taps into subconscious fears of penetration, infection, and the body being usurped. Giger’s facehugger design (grasping hands with a phallic tube it inserts down the throat) is essentially a face rape. The adult creature’s phallic head and slavering jaws, plus the womb-like ship interiors, create constant sexual menace.

The Feminist Hero in Space

Unlike many horror films of its era, Alien offers a strong, resourceful protagonist in Ellen Ripley. The suggestion to cast Ripley as a woman was quietly revolutionary. All the crew were originally written without specified genders, allowing a female lead to arise organically.

Ripley emerges as the quintessential “Final Girl” of horror, but in a sci-fi setting. She doesn’t kill the monster through brawn. Instead, she survives through level-headed action, luck, and sheer will. Ripley is never objectified, holds her own among men, and saves herself without needing a male rescuer.

The film’s authors and Scott made the crew gender-interchangeable, giving Alien a progressive edge. Many commentators see Ripley as a feminist hero. She faces down both a ravenous phallic nightmare and patriarchal corporate betrayal (Ash and “Mother” symbolically represent the Company’s cold authority), and she endures.

Ripley also shows compassion, insisting on trying to save the cat and grieving for her crewmates. This mix of strength and empathy helped audiences connect with the film in a genre often criticized for disposable female victims.

Corporate Malfeasance and Paranoia

Another layer of Alien’s narrative is the cynical depiction of the corporation (visible as “Weylan-Yutani” on ship monitors, later established as “Weyland-Yutani” in Aliens) as valuing profit and bioweapons over human life. When Ash’s secret orders are revealed (“bring back organism, crew expendable”), it casts the ordeal in a new light: the crew were sacrificial pawns in a corporate gambit.

This theme resonated in the post-Vietnam, post-Watergate 1970s, when distrust of corporations and government was high. It adds science fiction satire: in the future, even the far reaches of space are controlled by uncaring conglomerates that see their employees as expendable assets.

The Company’s actions introduce a theme of betrayal from within. The supposed protector (science officer) is actually a dangerous threat. This twist amps up tension between humanity and technology: Ash represents cold, hyper-rational machines serving corporate interests, juxtaposed against Ripley’s human intuition and survival instinct.

Atmosphere of Isolation and the Unknown

The film’s tagline, “In space, no one can hear you scream,” perfectly encapsulates the theme of isolation. The Nostromo crew are millions of miles from help, completely alone in the void. This allowed Alien to be essentially a haunted-house thriller in space.

The ship’s dark corridors, the constant sense of something lurking nearby, and the inability to escape (space is an ultimate closed environment) all contribute to pervasive claustrophobia.

The film also emphasizes the unknown. The derelict ship and Space Jockey are never explained, the creature’s full capabilities remain unclear, and even by the end we know little about what it truly is or where it came from. This Lovecraftian avoidance of clear explanation adds to the terror. Both O’Bannon and Giger admired H.P. Lovecraft, and O’Bannon stated that Alien is “Lovecraftian in tone,” about unknowable horrors and dread of the cosmic unknown.

The film never demystifies the creature. It remains a nightmare, not a scientifically dissected organism. This preserves its mythic quality and makes the themes more impactful.

Reception and Box Office Success

Box Office Domination

Alien opened in limited U.S. release on May 25, 1979 (Memorial Day weekend) in approximately 90–91 theaters, grossing $3.53 million over the 4-day weekend with a per-screen average of approximately $38,767, reportedly a record at the time. The film then went into wide U.S. release on June 22, 1979 and spent weeks as the #1 film in America.

By the end of its first run, Alien earned approximately $78.9 million domestically and about £7.9 million in the UK, making it one of the top-grossing films of 1979. Worldwide box office estimates range from $104 million to $188 million, highly profitable against its production budget of about $11 million (reported range $8.4–14M).

The film ranked as the #5 movie of 1979 in North America. In the UK, it stayed #1 for eight weeks, a rare feat.

Critical Reviews: Mixed to Positive

On initial release, Alien received a mixture of awe and reservation from critics. Many praised the visuals and terror, but some found it derivative or shallow.

Positive Reviews: Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert gave it two “yes” recommendations on Sneak Previews. Ebert called it “one of the scariest old-fashioned space operas” he could remember. Siskel gave it 3 out of 4 stars, predicting Weaver “should become a major star” and describing Alien as “an accomplished piece of scary entertainment.”

Mixed/Negative Reviews: Some mainstream outlets were less impressed. The Time Out review sniped that the film was an “empty bag of tricks” with great production values but “imaginative poverty” in content. The New York Times critic Vincent Canby felt it was effective viscerally but not much more, basically a B-movie story after the shocks wore off.

Even Roger Ebert, who enjoyed the ride initially, tempered his praise by saying the adult creature was the least scary part. However, he would later revise his opinion upward significantly.

Audience Reaction and Word of Mouth

Audiences in 1979 largely loved the film. Sneak previews around the country were strategically done to build word of mouth. An infamous preview in Dallas had viewers screaming. Editor Terry Rawlings said people were so frightened some ran out, and many were utterly glued to their seats by terror.

Sci-fi fandom embraced the film. It won the Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation (beating even Star Trek: The Motion Picture). It also swept Saturn Awards for Best Science Fiction Film, Best Director, and Best Supporting Actress (Cartwright).

Awards and Recognition

Alien garnered both genre awards and mainstream honors:

Academy Awards (1980): Won Best Visual Effects (H.R. Giger, Carlo Rambaldi, Brian Johnson, Nick Allder). Nominated for Best Art Direction.

BAFTA Awards (1980): Won Best Production Design (Michael Seymour, Leslie Dilley, Roger Christian) and Best Sound (Derrick Leather, Don Sharpe, Jim Shields, Geoff Unsworth). Nominated for Best Film Music (Jerry Goldsmith), Best Editing (Terry Rawlings), Best Supporting Actor (John Hurt), and Most Promising Newcomer (Sigourney Weaver).

Hugo Award (1980): Won Best Dramatic Presentation.

Saturn Awards (1979): Won Best Science Fiction Film, Best Director (Ridley Scott), and Best Supporting Actress (Veronica Cartwright).

National Film Registry: Selected for preservation by the U.S. Library of Congress in 2002, marking it as “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”

AFI Rankings: Ranked #7 on AFI’s Top 10 Sci-Fi Films (2008) and #6 on AFI’s 100 Years… 100 Thrills (2001), reflecting its enduring impact on American cinema.

Critical Reappraisal

In the years after 1979, Alien’s reputation only grew. By the early 2000s, critics who might have once dismissed it came to acknowledge it as a masterpiece. Roger Ebert revisited Alien in 2003 for his “Great Movies” series, giving it a full 4 stars and praising its originality and pacing. He noted the film had become “one of the most influential of modern action pictures.”

Many film scholars now study Alien for its genre-blending and thematic richness. Empire magazine’s poll in 2008 ranked it the 33rd greatest movie ever. The character of Ripley routinely tops lists of best film heroes, especially female protagonists.

Legacy and Influence: Changing Cinema Forever

The Franchise Phenomenon

Alien spawned an entire multimedia franchise:

Aliens (1986): James Cameron’s action-focused sequel was immensely successful and cemented Ripley’s pop culture status. Weaver earned an Oscar nomination for the role. This sequel introduced the term “Xenomorph” (spoken by Lt. Gorman), which fans and merchandise later popularized as the species name.

Alien³ (1992) and Alien: Resurrection (1997): These sequels had mixed reception but maintained fan interest.

Prometheus (2012) and Alien: Covenant (2017): Ridley Scott returned to explore the origins of the Space Jockey and the creature.

Alien: Romulus and Alien: Earth (TV series, 2025): The franchise continues with new entries over 45 years after the original.

Influence on Sci-Fi and Horror

Alien essentially created the “space horror” subgenre template. After Alien, the idea of a claustrophobic, R-rated science fiction film became viable. The lived-in, industrial look became more common (influencing films like Outland (1981) and Blade Runner (1982)).

The bleak tone proved that sci-fi cinema could be adult and pessimistic, helping pave the way for the cyberpunk and dystopian sci-fi wave of the 1980s. Films like John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982) might not have gotten made if Alien hadn’t proven audiences would accept intense horror in a sci-fi context.

Contemporary filmmakers frequently pay homage. Pitch Black (2000), Life (2017), and countless others follow Alien’s formula. Video games, especially the Dead Space series, owe a huge debt to Alien’s aesthetic and tension.

Design and Aesthetic Influence

H.R. Giger’s biomechanical style influenced a generation of artists. His design work started appearing in album artwork, tattoos, and countless derivative works. The look of the creature (eyeless, skeletal, with an elongated head) became a new template beyond the traditional bug-eyed green alien.

The concept of a monster with multiple growth stages (facehugger to chestburster to adult) influenced later creature features, including The Thing (1982) with its shape-shifting alien.

Pop Culture Footprint

Alien has been referenced and parodied extensively:

Spaceballs (1987): John Hurt cameoed to spoof his chestburster scene, with an alien bursting out, putting on a top hat, and singing “Hello my baby!”

TV Shows: The Simpsons, South Park, and countless others have riffed on Alien, commonly the chestburst or the tagline.

Catchphrases: “In space, no one can hear you scream” gets repurposed in jokes and memes constantly.

The character of Ellen Ripley became a pop culture icon, referenced whenever a strong female hero emerges. The term “chestburster” is now a common metaphor for anything dramatic erupting violently from within.

Expanded Universe

Alien’s universe expanded through comics (Dark Horse Comics launched an Aliens series in 1988), novels (Alan Dean Foster’s 1979 novelization and subsequent books), and video games. Alien: Isolation (2014) was acclaimed for capturing the look and feel of Ridley Scott’s original, with retro-technology and slow-burn tension.

The Alien vs. Predator crossover concept started in comics and games, eventually leading to two films (2004, 2007). The creature is now instantly recognizable, alongside Dracula or Godzilla in the pantheon of movie monsters.

Home Media and Marketing

The Iconic Marketing Campaign

Alien’s promotional campaign in 1979 is often hailed as a masterstroke. The poster featured a mysterious egg with a fissure of glowing light against a black background, with the tagline “In space, no one can hear you scream.” This tagline was created by Barbara Gips (wife of art director Philip Gips) and brilliantly encapsulated the film’s premise in one chilling sentence.

The first teaser trailer was equally enigmatic: a montage of unnerving images set to eerie music, ending with the egg cracking and the tagline. This coy approach built immense curiosity. Audiences went in not entirely sure what the “alien” looked like, only that it was terrifying.

The film received an “X” certificate in the UK upon release (restricting it to ages 18+), which helped market it as a serious, adult horror film and enhanced its reputation as a must-see shocker.

Home Video Evolution

Alien has seen releases on every format:

1980s: Available on VHS and Betamax, reportedly grossing an additional $40.3 million in US rental revenue.

1990s: Multiple VHS releases, trilogy box sets, and LaserDisc editions with deleted scenes and commentary.

1999: First DVD release in “The Alien Legacy” set.

2003: The Alien Quadrilogy DVD set included theatrical and alternate cuts plus extensive documentaries. The “Director’s Cut” of Alien included the famous deleted cocoon scene, though Ridley Scott clarified that the 1979 theatrical cut remained his preferred version.

2019: A 4K remaster for the 40th anniversary on UHD Blu-ray, with the film looking better than ever. Limited theatrical re-releases in 2019 and 2024 for anniversaries.

Merchandise and Collectibles

Despite the R-rating, merchandise was produced:

1979: Kenner released an 18-inch creature action figure aimed at children. Due to parent complaints about marketing an R-rated monster toy to kids, it was pulled from many stores and became a collector’s item. Model Products Corporation made a 12-inch plastic model kit. Trading cards and a novelization by Alan Dean Foster were released.

Modern Era: Companies like NECA and McFarlane Toys produce detailed collectible figures. Board games include “Alien: Fate of the Nostromo” (2021). High-end prop replicas and costumes are available for cosplay.

Video Games: From the 1982 Atari 2600 game to modern titles like Alien: Isolation (2014), the franchise has maintained a strong gaming presence.

Why Alien Endures: A Timeless Masterpiece

More than four decades after its release, Alien remains potent. New viewers continue to discover it and find that even with advances in CGI and filmmaking, Alien still looks amazing and feels terrifying.

Technical Excellence

The practical effects, particularly the chestburster sequence, still shock audiences. The creature design by Giger remains one of the most iconic in cinema history. The production design creates a believable, lived-in future that grounds the horror in reality.

Thematic Depth

Alien operates on multiple levels: as primal horror, as sci-fi cautionary tale, and as metaphorical commentary on sex, biology, and corporate greed. This richness invites repeated viewing and analysis.

As Roger Ebert reflected, Alien is “a much more cerebral movie than its sequels, with the characters (and the audience) genuinely engaged in curiosity about this weirdest of lifeforms.” The films that followed often imitated Alien’s thrills but “not its thinking.”

Cultural Impact

Alien proved that genre films could be both commercially successful and artistically respected. It elevated the craft of sci-fi/horror filmmaking and influenced countless directors, designers, and storytellers.

The film’s influence permeates design, storytelling, and our collective nightmares about what might be out there in the dark reaches of space. Horror director Eli Roth said of seeing Alien at age 8: “it traumatized me… I actually threw up I was so nervous after I saw it, but that’s like the highest compliment you can give a horror film.”

Conclusion: The Perfect Organism

Alien stands as a shining example of how a film can be both a piece of art and a pop culture phenomenon. From Dan O’Bannon’s nightmarish screenplay to H.R. Giger’s biomechanical designs, from the shocking chestburster to Sigourney Weaver’s iconic performance as Ripley, every element came together to create something truly special.

The film transformed science fiction by proving space adventures didn’t have to be optimistic. It revolutionized horror by bringing genuine terror to a futuristic setting. It gave cinema one of its greatest heroes in Ellen Ripley and one of its most terrifying monsters in the creature that would later be called the Xenomorph.

Whether you’re watching it for the first time or the fiftieth, Alien delivers a masterclass in suspense, atmosphere, and pure terror. Its tagline remains as true today as it was in 1979: In space, no one can hear you scream.

But on Earth, in darkened theaters and living rooms around the world, audiences have been screaming for over 45 years, and they show no signs of stopping.