In the dark corners of cinema history, where shadows dance like restless spirits across silver-stained walls, Tod Browning’s Dracula 1931 rises from its tomb – a masterpiece that bleeds atmosphere from every frame. The year was 1931, and sound had just sunk its fangs into the flesh of Hollywood, transforming the silent scream into an audible nightmare. What emerged was more than just Universal Studios’ first horror talkie; it was a cultural phenomenon that would define the vampire genre for generations to come.

The production history itself reads like a gothic tale of fate and circumstance. Universal Studios, sensing blood in the water after the success of the 1927 Broadway production, acquired the rights and appointed Tod Browning to direct. Browning, still mourning the loss of his frequent collaborator Lon Chaney Sr. (who was originally envisioned for the role of Dracula), found himself grappling with personal demons during filming. The whispers of his struggles – his reported alcoholism, his delegation of directorial duties to cinematographer Karl Freund – add another layer of darkness to the film’s creation. Like Dracula himself, the film emerged from a crucible of pain and transformation.

From the first frame, we’re thrust into a world where silence becomes a weapon. The carriage wheels creak through the Carpathian peaks, each turn grinding against stone like bones in a crypt. The opening sequence remains a masterclass in mounting dread – the long, slow shots of the carriage winding through the mountains, the villagers crossing themselves at the mention of Dracula’s name, the wonderful moment when Renfield’s laughter dies in his throat as he realizes what awaits him. This isn’t just scene-setting – it’s pure cinema, operating on a level beyond mere narrative.

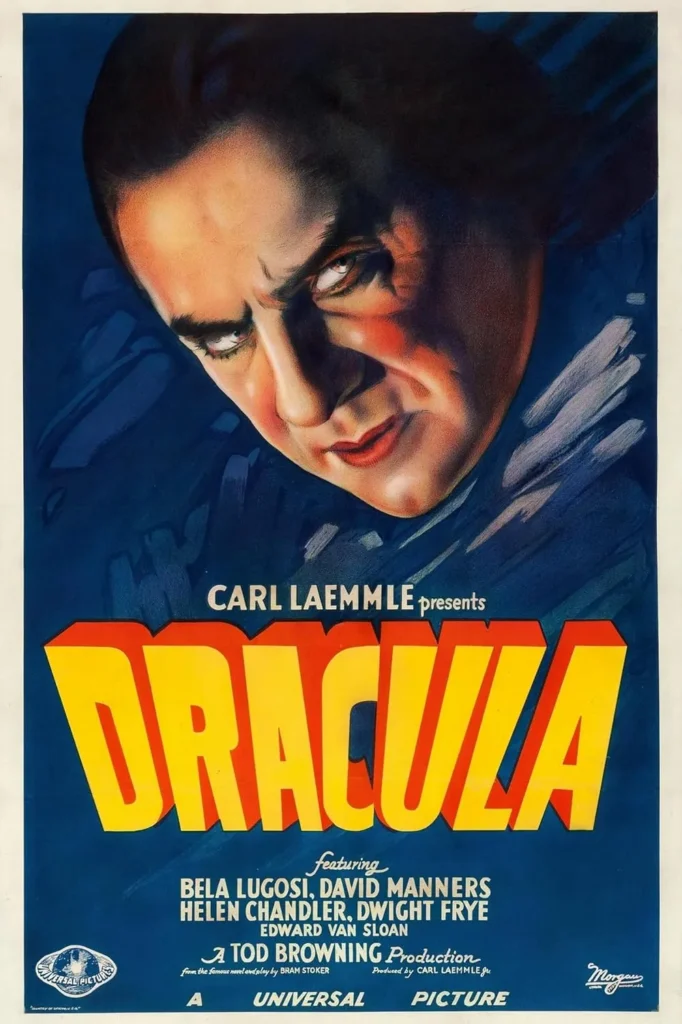

At the heart of this gothic nightmare stands Bela Lugosi, a Hungarian exile who would become forever entombed in the role of Count Dracula. His performance isn’t just acting – it’s possession. Every gesture flows like dark water, each word drops from his lips like honey laced with poison. What fascinates me most about Lugosi is the profound personal history he brought to the role. Here was an actor who fled his homeland for political reasons, who carried the weight of exile like a cross. His preference for solitude, his dedication to sculpting rather than the Hollywood social scene, all fed into his portrayal of Dracula as an aristocratic outsider, forever separate from the world he inhabits.

The film’s cinematography, crafted by the masterful Karl Freund, fresh from the expressionist crucible of “Metropolis,” transforms every frame into a baroque painting come to life. Freund’s innovative use of light and shadow creates a world where darkness itself becomes a living entity. His camerawork is particularly brilliant in the castle sequences – notice how the camera prowls through Dracula’s domain like a ghost, revealing cobwebs that hang like funeral veils and stairs that spiral down into madness. Each shadow is a character, each shaft of light a weapon in the eternal war between good and evil.

What draws me back to this film time and again is its masterful use of silence. In these early days of sound cinema, when many films were drowning in dialogue, “Dracula” understood the power of the unsaid. The long stretches of silence in Dracula’s castle aren’t technical limitations; they’re artistic choices that create an atmosphere of suffocating dread. When the Count moves through his domain, there’s no music, no sound effects – just the weight of centuries pressing down like a tombstone.

Dwight Frye’s Renfield provides the film’s most visceral horror. His transformation from proper English solicitor to bug-eating servant is a descent into chaos that still haunts the imagination. His laugh – that horrible, hysterical cackle – echoes through time like a warning of sanity’s fragility. The scene where he interrupts the discussion between Van Helsing and Dr. Seward, raving about his arrangement with Dracula, remains one of cinema’s most disturbing portraits of madness.

Edward Van Sloan’s Van Helsing provides the perfect counterpoint to Lugosi’s supernatural menace. His performance embodies rational enlightenment facing ancient darkness, science confronting superstition. The confrontation between Van Helsing and Dracula in Dr. Seward’s study, where the Count’s lack of reflection reveals his true nature, crackles with intellectual and supernatural tension. Yet the film suggests that some truths lie beyond reason’s reach, in the realm of folklore and faith. When Van Helsing brandishes his crucifix, we’re watching more than just a prop – we’re seeing the power of belief made manifest.

What fascinates me most is how the film’s very limitations become its strengths. The technical constraints of early sound cinema forced Browning and his team to rely on atmosphere rather than explicit horror. Watch how the camera lingers on Lugosi’s face, his eyes burning with otherworldly intensity. Notice how the sound drops away entirely during key moments, leaving us alone with our mounting dread. These weren’t just technical compromises – they were inadvertent strokes of genius that created a new vocabulary of horror.

The film’s treatment of sexuality and death – twin shadows that dance through vampire mythology – is surprisingly sophisticated for its era. Dracula’s attacks are clearly coded as seduction, his victims drawn into an embrace that’s both death and dark ecstasy. The camera never shows the actual bite – it doesn’t need to. The horror lives in suggestion, in the space between what we see and what we imagine. The transformation of Mina from innocent maiden to creature of the night represents both violation and dark liberation, a commentary on the restrictive sexual mores of the era.

Consider the film’s remarkable commercial impact – selling 50,000 tickets within 48 hours of its opening at New York’s Roxy Theatre. In the midst of the Great Depression, audiences flocked to see a story about an aristocratic predator who feeds on the living. The metaphorical implications are impossible to ignore. The film tapped into something primal in the American psyche, a fear of both the foreign and the familiar, of both change and stagnation.

The Spanish-language version, shot simultaneously on the same sets with a different cast and crew, serves as a fascinating counterpoint to Browning’s vision. While some critics consider it technically superior, with more fluid camera movements and elaborate staging, it lacks the hypnotic power of Lugosi’s performance. The existence of these twin films adds another layer of uncanny doubling to the Dracula myth, each version reflecting different aspects of the same dark story.

I’m particularly struck by the film’s use of space and architecture. Dracula’s castle, with its impossibly high ceilings and perpetual shadows, becomes a character in itself. The transition from the gothic horror of Transylvania to the ordered, rational world of London creates a powerful contrast. Yet even in London, Dracula brings the ancient darkness with him, transforming drawing rooms and bedrooms into spaces of supernatural terror.

Modern audiences might find the pacing glacial, the effects primitive. But this is precisely where “Dracula” draws its power. In an age of CGI excess, there’s something profoundly unsettling about the simplicity of a shadow on a wall, the flutter of a cape, the hypnotic gaze of a predator sizing up its prey. The film’s structure mirrors the vampire’s own nature – it’s both dead and alive, both primitive and sophisticated, both highly theatrical and deeply cinematic.

The film’s influence on contemporary horror cinema cannot be overstated. Modern filmmakers continue to draw from its visual vocabulary – the use of negative space, the power of the unseen, the marriage of elegance and terror. When I watch recent vampire films like “Only Lovers Left Alive” or “Let the Right One In,” I see echoes of Browning’s approach to supernatural horror as a vehicle for exploring human nature. Even non-vampire horror films owe a debt to “Dracula’s” understanding that true terror lives in anticipation rather than revelation.

Critics over the decades have wrestled with the film’s legacy. Some modern viewers might bristle at its treatment of women, who largely serve as vessels for male desire and corruption. Yet I find this criticism overlooks the subtle subversion at play – the vampire’s bite represents not just violation but liberation from Victorian constraints, a dark path to power in a world that denied women agency. The film’s pacing, often cited as glacial by contemporary standards, creates what I see as a hypnotic dreamscape where time itself becomes elastic and uncertain.

What strikes me most personally about “Dracula” is how it continues to reveal new layers with each viewing. Recently, I was struck by its exploration of immigration and assimilation – Dracula as the ultimate “other” attempting to infiltrate British society. This reading feels particularly resonant in our current political climate, where fears of the foreign continue to shape public discourse. The Count’s attempts to “pass” in London society, his careful cultivation of aristocratic manners masking his true nature, speaks to timeless anxieties about identity and belonging.

The film’s technical “limitations” – the long silences, the theatrical staging, the reliance on suggestion rather than spectacle – have aged into strengths. In an era of sensory bombardment, “Dracula’s” restraint feels revolutionary. Its power lives in the spaces between words, in the shadows between frames, in all the things it refuses to show us. Every time I revisit it, I’m struck by how modern horror cinema, for all its technical sophistication, rarely achieves the same level of sustained dread.

Looking back through nearly a century of fog, “Dracula” stands as more than just a horror film. It’s a piece of dark poetry written in light and shadow, a meditation on death, desire, and the price of immortality. Every vampire film that followed exists in its shadow, every actor who donned the cape and fangs must contend with Lugosi’s ghost. The film’s DNA has seeped into our cultural bloodstream, influencing everything from fashion to music to literature.

When the credits roll and the lights come up, we might tell ourselves it’s just a movie, just shadows on a screen. But somewhere in the back of our minds, we hear Lugosi’s voice whispering across the decades: “There are far worse things awaiting man than death.” And in that moment, we believe him. Because “Dracula” is more than a movie – it’s a doorway into darkness, a glimpse of the eternal night that waits for all of us. In Lugosi’s hypnotic gaze, we see our own mortality reflected back at us, transformed into something both terrifying and seductive. The count’s invitation still echoes through time: “Listen to them, the children of the night. What music they make!” And we’re still listening, still watching, still drawn to this ancient dance of light and shadow, life and death, desire and dread.