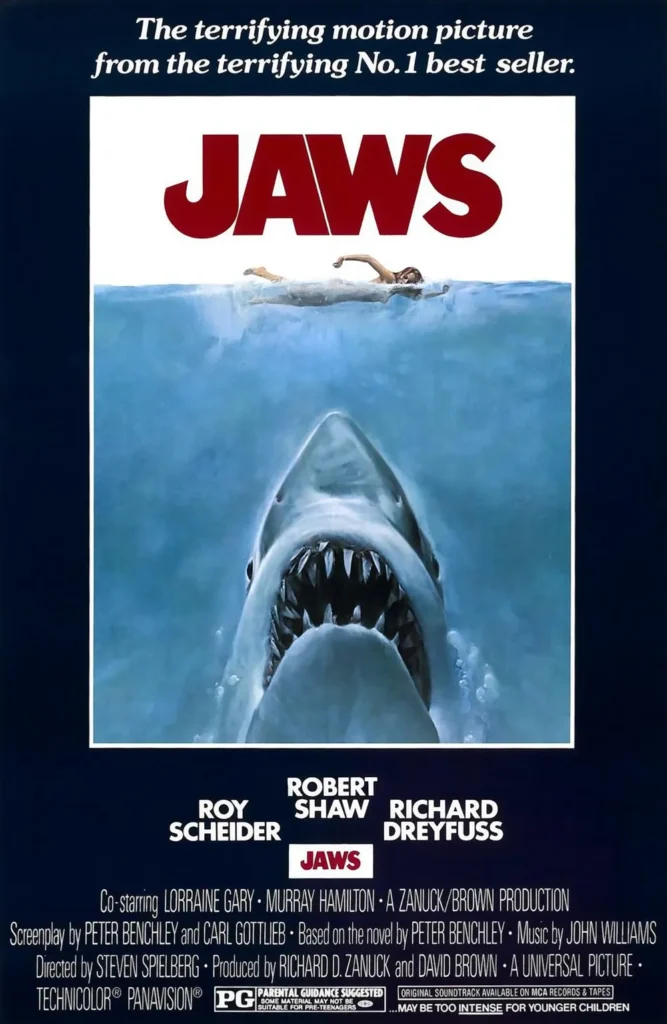

Jaws 1975 rips through the surface of American cinema like a ruthless predator, leaving behind the bloodied remains of conventional filmmaking and birthing something entirely new – a raw, pulsing entity that would forever alter the DNA of Hollywood. Steven Spielberg’s masterpiece doesn’t just swim in the waters of horror and suspense; it devours them whole, creating a feeding ground of primal terror that still churns in our collective nightmare nearly fifty years later.

In the sun-bleached tourist haven of Amity Island, death arrives without ceremony. A young woman’s midnight swim becomes a violent ballet of thrashing limbs and desperate screams, setting the stage for a battle that transcends mere monster movie tropes. This isn’t just about a shark – it’s about the rot beneath the surface of American life, the way we sacrifice truth on the altar of commerce, and the price we pay for our arrogance in the face of nature’s cold indifference.

Roy Scheider’s Chief Martin Brody stands as our everyman prophet, a cop who trades the violent streets of New York for what he thinks will be the quiet shores of Amity. Instead, he finds himself caught in a tide of political corruption and willful blindness, embodied by Murray Hamilton’s Mayor Vaughn – a man whose anchor of denial drags the whole town deeper into blood-stained waters. Brody’s journey from water-fearing outsider to reluctant warrior mirrors our own primal struggle with the unknown depths that lurk beyond our comfortable shores.

The film’s holy trinity comes together in its final act – Scheider’s Brody, Richard Dreyfuss’s Hooper, and Robert Shaw’s Quint form a powder keg of conflicting personalities aboard the Orca. Their hunt for the great white becomes a descent into madness, a war story where the enemy remains largely unseen but ever-present. Shaw’s Quint, scarred by his experience on the USS Indianapolis, delivers a monologue that stands as one of cinema’s most haunting moments – a raw confession of survival and guilt that turns this summer thriller into a meditation on man’s helplessness in the face of nature’s perfect killing machine.

Spielberg, only 27 when he made Jaws, transforms technical limitations into pure artistic gold. The malfunctioning mechanical shark, affectionately nicknamed Bruce, forced him to suggest rather than show – and in doing so, he tapped into something far more terrifying than any rubber monster could provide. The unseen presence beneath the waves becomes a canvas for our deepest fears, painted in broad strokes of anticipation and dread. Every ripple, every shadow, every yellow barrel bobbing to the surface carries the weight of impending doom.

John Williams’ score doesn’t just accompany the film – it possesses it. The iconic two-note theme burrows into your brain like a primal warning signal, a prehistoric memory of being prey. It’s simple, relentless, effective – like the shark itself. When that music starts, something deep in your lizard brain knows it’s time to run, even as you sit safely in your seat, miles from any ocean.

The film’s cinematography by Bill Butler is a masterclass in visual storytelling. The camera becomes another character, sometimes floating menacingly at water level, other times trapped in the claustrophobic confines of the Orca’s cabin. The infamous dolly zoom shot of Brody on the beach, as he witnesses a shark attack, physically manifests his horror in a way that words never could. It’s visceral, immediate, and unforgettable.

But what truly elevates Jaws beyond its genre trappings is its understanding of human nature. The film is populated with real people making real choices, some heroic, some cowardly, all understandable. When Mrs. Kintner, dressed in funeral black, slaps Brody and accuses him of knowing about the shark before her son’s death, we feel the weight of every choice that led to that moment. The film never lets us forget that behind the thrills and suspense, real human lives hang in the balance.

The final act aboard the Orca is pure cinematic alchemy. Three men, each representing different aspects of masculinity and human response to crisis, confined in a floating coffin with a monster circling below. Quint’s descent into Ahab-like obsession, Hooper’s scientific rationality crumbling in the face of primal terror, and Brody’s transformation from reluctant participant to ultimate survivor create a perfect storm of character dynamics. When Quint slides down the deck into the shark’s maw, it’s both horrifying and somehow inevitable – a warrior’s death that feels pulled from some ancient maritime myth.

What makes Jaws resonate decades later isn’t just its technical brilliance or its ability to scare – it’s the film’s understanding of what truly frightens us. It’s not the shark itself, but what it represents: the unknown, the uncontrollable, the primal forces that lurk beneath the surface of our civilized world. When Brody finally blows the shark to kingdom come with a perfectly placed shot to the oxygen tank, his victory feels earned not just through luck or skill, but through a hard-won understanding of his own courage.

The film’s influence on cinema cannot be overstated. It didn’t just create the summer blockbuster – it showed how popular entertainment could be made with intelligence, craft, and genuine artistry. Every shark movie since has lived in its shadow, every summer thriller has tried to capture its magic, but none have matched its perfect blend of primal fear and human drama.

Watching Jaws today is like witnessing a perfect storm of filmmaking elements coming together. The production difficulties, the young director’s innovative solutions, the perfect cast, the legendary score – all of these elements could have resulted in disaster. Instead, they combined to create something timeless, a film that works as both a crowd-pleasing thriller and a sophisticated study of human nature under pressure.

The legacy of Jaws extends far beyond its impact on film history. It fundamentally changed our relationship with the ocean and its apex predators – for better or worse. While the film’s portrayal of sharks as mindless killing machines has done real damage to conservation efforts, it also forced us to confront our place in the natural world. We are not its masters, but merely visitors in a realm where our technology and our civilized pretenses mean nothing.

As the final frames show Brody and Hooper paddling back to shore on their makeshift raft, we’re left with a sense not just of relief, but of profound respect – for the power of nature, for the courage of ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances, and for the art of filmmaking itself. Jaws remains, after all these years, not just a great thriller, but a testament to what cinema can achieve when it dares to dive deep into the dark waters of our collective fears and emerge with something truly profound.

In the end, Jaws is more than a movie about a shark. It’s about the thin line between civilization and chaos, about the price of ignorance and the cost of courage, about the way fear can unite or divide us. It’s a perfect film – not despite its flaws and production difficulties, but because of them. Like the shark itself, it is a pure expression of what it means to be alive, to fight, to survive. And like the waters it made us fear, it remains deep, dangerous, and endlessly fascinating.