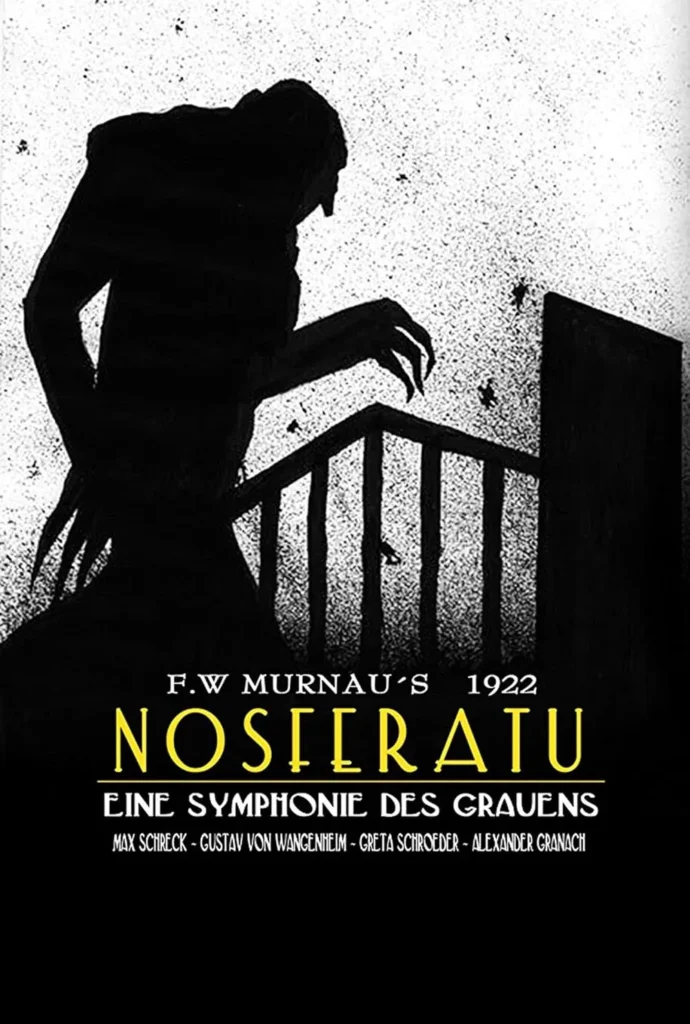

In the haunted realm between dreams and nightmares, F.W. Murnau’s “Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror” (1922) emerges as an immortal shadow that refuses to fade in the light of modern cinema. This unauthorized adaptation of Bram Stoker’s “Dracula” transcends its modest origins to become a masterwork of German Expressionism and a foundational text in the language of horror cinema. A film that nearly vanished into the void of lost art – thanks to Stoker’s widow’s successful lawsuit demanding all copies be destroyed – has instead risen to claim its place among the greatest films ever created, even earning the Vatican’s blessing as one of the 15 finest examples of cinematic art.

The film’s journey from initial dismissal to critical acclaim mirrors its own themes of transformation and resurrection. Early critics, including Mordaunt Hall of the New York Times, dismissed it as lacking thrills, suggesting it was “the sort of thing one could watch at midnight without its having much effect upon one’s slumbering hours.” Time has proven such assessments spectacularly wrong, with modern audiences and critics alike recognizing its power to create a “slow-building, impending sense of doom” that lingers long after viewing. By 2022, its status was cemented when the prestigious Sight and Sound poll ranked it among the greatest films ever made.

A Dance of Light and Shadow: Visual Poetry in Motion

The raw technical mastery of “Nosferatu” becomes apparent from its opening frames. Murnau’s revolutionary approach to composition transforms even mundane scenes into exercises in mounting dread. When Hutter first arrives at the inn before his fateful journey to Orlok’s castle, the simple act of opening a window becomes laden with ominous significance. The director’s use of deep focus photography, revolutionary for its time, allows viewers to simultaneously observe the foreground action while keeping an eye on the threatening darkness that lurks just beyond the frame.

Murnau’s masterpiece draws its power from the raw vocabulary of German Expressionism, wielding shadow and light like instruments in a visual symphony. The film’s signature moments are painted in darkness – none more iconic than Count Orlok’s elongated shadow ascending the stairs toward his victim’s chamber, a moment that has burned itself into horror’s collective memory. These shadows aren’t mere absence of light; they’re living things, extensions of Orlok’s malevolent presence that stretch across walls and souls alike.

The cinematography breaks from convention with deliberate unease. The camera moves with a distinctive “bump” during Orlok’s appearances, creating a world physically untethered from reality. This technical choice mirrors the psychological disturbance at the heart of the narrative – we’re not just watching a horror story; we’re experiencing a descent into nightmare logic where the familiar becomes twisted and wrong.

Every frame is composed with painterly precision, transforming simple locations into expressionistic landscapes of the mind. The castle sequences particularly exemplify this approach, with their distorted architecture and stark contrasts creating a sense of space that feels both claustrophobic and impossibly vast. Murnau understood that horror lives in the spaces between what we see and what we imagine, and he uses every tool in his arsenal to exploit this truth.

The film’s innovative use of music further enhances its atmospheric power. Though silent, the original score functions as a true symphony, building tension and releasing it in carefully orchestrated movements. This groundbreaking approach to film scoring would influence generations of horror filmmakers, demonstrating how music could be used to manipulate audience emotions and enhance the visual experience.

Narrative Shadows: A Tale of Terror and Sacrifice

The story follows Thomas Hutter, a real estate agent dispatched to Transylvania by his employer, the mysterious Knock, to facilitate Count Orlok’s purchase of a house in their German town of Wisborg. This seemingly simple premise unfolds into a tapestry of dread, with each scene building upon the last like gathering storm clouds.

The film is rich with prophetic detail and symbolic weight. When Ellen, Hutter’s wife, mourns the “death” of flowers he brings her early in the film, it’s more than just a tender moment between lovers – it’s a harbinger of the sacrifice to come. These subtle touches demonstrate Murnau’s mastery of visual storytelling, where even the smallest gesture carries the weight of fate.

The journey to Orlok’s castle is filled with mounting tension, as locals at an inn warn Hutter of werewolves and evil spirits. The discovery of the book “Of Vampires, Terrible Ghosts, Magic, and The Seven Deadly Sins” serves as both exposition and ominous foreshadowing. Each step of Hutter’s journey draws him deeper into a world where reality begins to blur and supernatural horror becomes increasingly tangible.

At the heart of this darkness stands Max Schreck’s Count Orlok, a creation that redefined the vampire in cinema. Unlike the sophisticated, seductive vampires that would follow, Orlok is a creature of pure horror. With his elongated fingers, pointed ears, and rat-like features, he emerges as something truly inhuman – a walking plague rather than a dark aristocrat. Schreck’s performance, though bound by the conventions of silent film, conveys volumes through posture and presence alone. His movements are unnaturally precise, suggesting something ancient trying to remember how to wear human skin.

The parallel storylines of Orlok’s journey by sea and the spreading plague create a mounting sense of inevitable doom. Murnau’s manipulation of time and space during these sequences demonstrates his mastery of parallel editing, a technique that was still in its infancy. The interweaving of Ellen’s psychic distress with the vampire’s approach creates a psychological connection that transcends physical distance, suggesting a supernatural bond that adds another layer of horror to the proceedings. The scenes of the empty ship drifting into harbor, its crew mysteriously decimated, represent some of the most effective maritime horror ever captured on film. The scenes aboard the death ship, where crew members succumb one by one to an unseen horror, represent some of cinema’s earliest and most effective examples of mounting dread through suggestion rather than explicit horror.

The Weight of History: Context and Creation

The film’s emergence from the crucible of the Weimar Republic cannot be overlooked. In the aftermath of World War I, Germany was a nation grappling with defeat, economic crisis, and social upheaval. This cultural anxiety manifests in every frame of “Nosferatu,” from its preoccupation with plague and societal collapse to its expressionistic distortion of reality itself. The vampire here becomes more than just a monster – he’s a physical embodiment of the fears haunting post-war Europe.

The production itself carries its own dark mythology. The unauthorized nature of the adaptation led to legal battles that nearly resulted in the film’s complete destruction. That it survived at all feels like a minor miracle, though this brush with oblivion has only enhanced its mystique. Modern viewers can’t help but wonder how many other masterpieces of early cinema were lost to similar fates.

Professor Bulwer’s lecture on predatory plants serves as more than mere exposition – it reflects the film’s broader themes about nature’s inherent cruelty and the thin line between scientific observation and supernatural horror. This scene, along with the asylum sequences featuring the mad Knock, demonstrates how the film weaves together scientific rationality and supernatural terror in ways that still resonate today.

Legacy of the Night: Impact and Influence

The technical innovations of “Nosferatu” extend far beyond its narrative achievements. Murnau’s masterful use of practical effects, particularly in scenes involving the vampire’s supernatural powers, set new standards for visual storytelling. The sequence where Orlok loads his coffins onto a cart, seemingly without physical assistance, creates an eerie sense of otherworldliness through simple yet effective in-camera techniques. These moments of practical magic, achieved through careful editing and multiple exposures, would influence generations of filmmakers in their approach to supernatural horror.

“Nosferatu” didn’t just influence horror cinema – it helped establish its fundamental grammar. The film’s innovative use of shadows, its emphasis on suggestion over explicit horror, and its introduction of sunlight as fatal to vampires have become genre staples. Yet even as these elements have been copied countless times, few films have matched “Nosferatu’s” ability to create sustained, atmospheric dread.

The film’s treatment of the vampire myth established new conventions while subverting others. Orlok’s destruction by sunlight – a fate not present in Stoker’s novel – became a cornerstone of vampire lore. His association with rats and plague added a dimension of scientific horror to the supernatural threat, creating a template for how horror films could blend real-world fears with supernatural elements.

The film’s influence extends far beyond horror, reaching into unexpected corners of popular culture. Its iconic imagery has been referenced everywhere from arthouse cinema to “SpongeBob SquarePants,” demonstrating its enduring power to capture the imagination. The 2000 film “Shadow of the Vampire” even reimagined its production through a meta-horror lens, suggesting that Max Schreck was actually a real vampire – a testament to the original film’s ability to blur the lines between art and nightmare.

Final Thoughts: An Eternal Symphony of Horror

A century after its creation, “Nosferatu” remains a testament to cinema’s power to articulate the unspeakable. While some of its techniques may appear dated to modern eyes, its core ability to unsettle and disturb remains undiminished. The film understands that true horror lives not in the jump scare or the revealed monster, but in the growing certainty that something is fundamentally wrong with the world we thought we knew.

Ellen’s sacrifice at the film’s climax – holding the vampire until dawn claims him – represents both the triumph of love over evil and the price such victory demands. This bittersweet conclusion elevates “Nosferatu” above simple horror into the realm of tragedy, suggesting that victory over darkness often requires its own form of darkness.

Murnau’s masterpiece reminds us that horror cinema at its finest isn’t just about frightening audiences – it’s about holding up a dark mirror to society’s fears and forcing us to confront what lurks in the shadows of our collective unconscious. In an era of CGI monsters and calculated shock effects, “Nosferatu” still teaches us that the most effective horror is that which makes us afraid of the dark spaces in our own minds.

This symphony of horror plays on, its notes echoing through the decades, reminding us that some shadows never truly fade – they just wait patiently for the light to dim once more. The film’s ultimate triumph lies not just in its ability to frighten, but in its power to remind us that true horror exists in the spaces between what we can see and what we can only imagine. In this sense, “Nosferatu” isn’t just a masterpiece of early cinema – it’s a timeless exploration of humanity’s deepest fears, a reminder that no matter how much we evolve, the darkness within and without continues to hold sway over our collective imagination.

As we approach the film’s second century, its influence only grows stronger. Modern horror directors continue to study and draw inspiration from Murnau’s techniques, recognizing that in an age of increasingly sophisticated special effects, the simple power of a shadow on a wall can still evoke primal fears that no amount of digital wizardry can match. “Nosferatu” stands as a testament to cinema’s unique ability to translate our darkest dreams into visual poetry, and in doing so, help us confront and perhaps even understand the shadows that haunt us all.