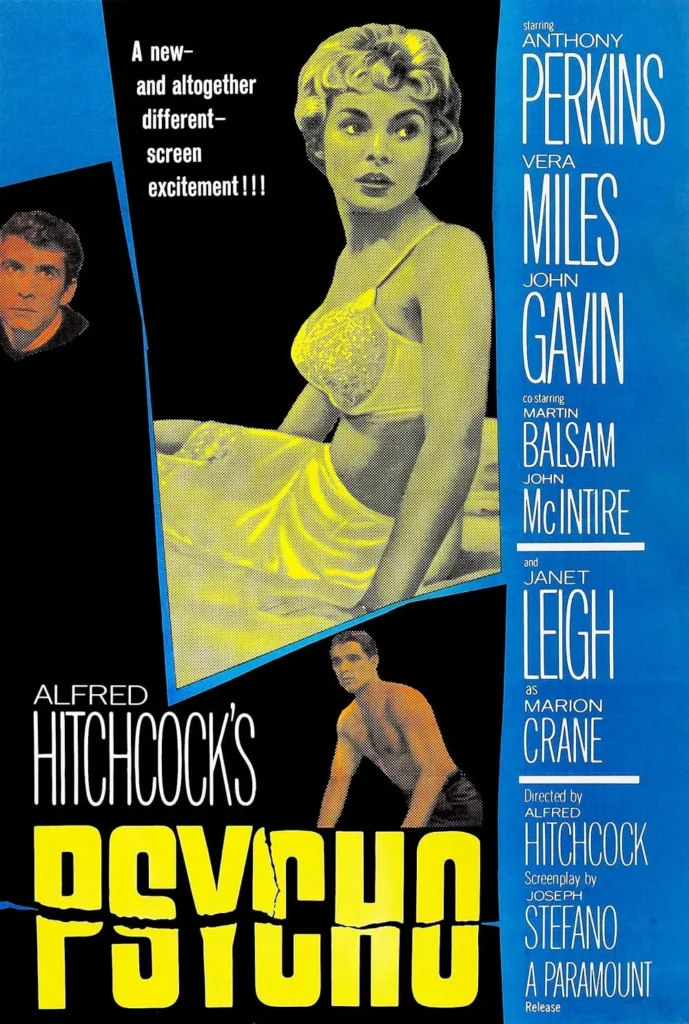

In the realm of American cinema, there exists a singular moment when everything changed – when the safe confines of Hollywood storytelling shattered like a mirror, leaving audiences to wade through the glittering shards of their own expectations. That moment was Psycho, Hitchcock’s masterwork of psychological terror that still draws blood sixty-plus years after its release.

The film opens like a razor slash across sun-bleached Phoenix, where Marion Crane’s afternoon tryst plants the seeds of desire that will bloom into destruction. Janet Leigh brings a raw vulnerability to Marion, a woman whose desperate grasp at happiness leads her down a rain-slicked highway toward oblivion. The $40,000 she steals isn’t just money – it’s the weight of every compromise, every small surrender that leads us into darkness.

But this isn’t really Marion’s story. It’s a brilliant feint by Hitchcock, who uses her flight from Phoenix as bait to lure us into the true heart of darkness: the Bates Motel, where Anthony Perkins’ Norman Bates waits like a spider in his web. Perkins delivers one of cinema’s most devastating performances, creating in Norman a creature of profound dysfunction masked by boyish charm. His nervous smile and stuttering politeness form a thin veneer over an abyss of psychological horror.

The film’s power lies in its ability to transform the mundane into the monstrous. Every frame pulses with potential menace – a highway patrolman’s mirrored sunglasses reflect Marion’s guilt back at her, the rhythmic sweep of windshield wipers becomes a metronome counting down to doom, and a roadside motel morphs into a gateway to hell. Hitchcock understood that true horror lives in the spaces between normalcy and madness, in the moments when reality begins to warp and bend.

The infamous shower scene arrives like a hammer blow to the temple. Hitchcock, working with his television crew and a modest budget, transforms porcelain and stream into an arena of primal terror. The sequence required 70 camera setups and a week to film, each frame meticulously crafted to maximize impact without explicit gore. Bernard Herrmann’s shrieking violins don’t just accompany the scene – they become the voice of the knife itself, scoring deep psychological wounds that never quite heal.

What fascinates me most about this sequence isn’t just its technical brilliance, but its profound impact on the viewer’s psyche. The murder occurs in what should be a moment of cleansing and redemption – Marion has decided to return the money, to set things right. The shower symbolizes her spiritual renewal, but Hitchcock transforms this private ritual of purification into an execution chamber. It’s a violation not just of Marion’s body, but of our fundamental sense of safety and order.

But what makes Psycho truly revolutionary isn’t just its violence or its technical mastery – it’s the way Hitchcock manipulates our sympathies. After Marion’s death, we’re left emotionally adrift, forced to transfer our connection to Norman. We watch him clean up “Mother’s” mess with a mixture of horror and sympathy, our moral compass spinning wildly as we find ourselves hoping he succeeds in hiding the evidence. Hitchcock makes us complicit in Norman’s madness, teaching us how easy it is to slip into darkness.

The film’s visual grammar speaks volumes through shadow and light. The imposing Victorian house looms over the modest motel like a manifestation of Norman’s fractured psyche – a gothic monument to madness in the midst of mid-century American banality. The interplay between these two spaces – the modern motel and the decaying mansion – creates a visual metaphor for Norman’s splintered identity.

Each time I revisit Psycho, I’m struck by the brilliance of its parlor scene. Norman’s stuffed birds loom over his conversation with Marion, their glass eyes watching with predatory intensity. Every line of dialogue carries double meaning: “We all go a little mad sometimes,” Norman says, in what might be the film’s most chilling moment of honesty. The taxidermied birds serve as perfect symbols – beautiful, preserved creatures forever frozen in artificial poses, just as Norman attempts to preserve the illusion of his mother’s existence.

As private investigator Arbogast (Martin Balsam) begins to probe the mystery of Marion’s disappearance, the film shifts into a different gear. His death on the staircase, shocking in its suddenness, reinforces the lesson of the shower scene: in Norman’s world, death comes without warning or mercy. The carefully constructed plot begins to peel away like old wallpaper, revealing the rotting psychological architecture beneath.

Vera Miles as Lila Crane brings a desperate determination to the film’s final act, her search through the Bates house becoming a descent into the layers of Norman’s psychosis. Each room she explores is a chamber in Norman’s damaged mind – his childhood bedroom frozen in time, Mother’s room a shrine to impossible preservation, and finally the fruit cellar where truth and madness become indistinguishable.

The film’s ending, with its psychiatric explanation of Norman’s condition, might seem anticlimactic to modern audiences accustomed to more ambiguous horror. But there’s something uniquely disturbing about the clinical dissection of Norman’s madness – the way it reduces the supernatural terror we’ve experienced to a set of psychological terms that somehow make it more, not less, frightening. The final shot of Norman/Mother’s face, smirking at some private joke as a fly crawls across his hand, suggests that no explanation can truly contain the horror we’ve witnessed.

Hitchcock’s technical innovations in Psycho cannot be overstated. The film’s black and white photography, initially a budgetary constraint, becomes a crucial artistic choice, stripping away the comfort of color to expose the stark shadows of human nature. The director’s use of the 50mm lens creates a natural perspective that makes us unwitting voyeurs, while his editing techniques – particularly in the shower scene – redefined what was possible in mainstream cinema.

The behind-the-scenes stories of Psycho‘s creation reveal Hitchcock’s obsessive attention to detail. He bought up copies of Robert Bloch’s novel to preserve the ending’s surprise, created elaborate publicity stunts to maintain secrecy, and even used chocolate syrup as a stand-in for blood in the shower scene. These weren’t just practical solutions – they were part of a larger strategy to create a new kind of cinematic experience, one that would shock audiences out of their complacency.

Bernard Herrmann’s score deserves special mention. Initially resistant to music in the shower scene, Hitchcock later admitted that the film’s impact owed at least a third of its success to Herrmann’s revolutionary string composition. The score doesn’t just accompany the action – it excavates the psychological substrata of each scene, revealing the churning emotions beneath the surface. The way the music stabs and slashes through the shower scene creates a visceral experience that bypasses our rational defenses.

What makes Psycho endure isn’t just its shock value or technical brilliance – it’s the way it taps into our deepest fears about identity and sanity. Norman Bates isn’t some supernatural boogeyman; he’s the boy next door whose psychological damage transforms him into something monstrous. The film suggests that madness isn’t some foreign invasion but a potential that lurks within ordinary human experience, waiting to emerge under the right conditions.

The film’s connection to real-life killer Ed Gein adds another layer of disturbing resonance. While the details differ significantly, this link to actual events grounds the horror in reality, suggesting that monsters don’t just exist in our imagination – they live among us, serve us coffee, make small talk about the weather. It’s this recognition that makes Psycho so profoundly unsettling.

Hitchcock’s manipulation of audience expectations throughout the film is masterful. He understood that true horror comes not from what we see, but from what we think we might see. The film plays with our anticipation like a cat toying with a mouse, building tension through suggestion and implication rather than explicit showing. Even the violence, shocking for its time, derives much of its power from what remains unseen.

The film’s exploration of voyeurism adds another layer of psychological complexity. Norman’s peephole, through which he watches Marion undress, mirrors our own position as viewers. We too are peeping toms, deriving pleasure from watching others in moments of vulnerability. Hitchcock makes us uncomfortably aware of our own voyeuristic tendencies, suggesting that the line between observer and participant, between normal and abnormal, isn’t as clear as we might like to think.

Psycho marked a seismic shift in American cinema, shattering taboos around violence, sexuality, and psychological content. Its influence reaches far beyond the horror genre, teaching filmmakers how to manipulate audience expectations and emotions with surgical precision. But perhaps its greatest achievement is the way it forces us to confront our own capacity for darkness, our own vulnerable psyches.

In the end, Psycho remains a perfect storm of artistic elements – Hitchcock’s masterful direction, Perkins’ haunting performance, Herrmann’s revolutionary score, and a script that cuts to the bone of human psychology. It’s a film that doesn’t just shock or frighten – it fundamentally alters how we understand ourselves and our capacity for both victimhood and monstrosity. In the Bates Motel’s grimy register, in the shadows of that Victorian mansion, in the empty stare of a preserved corpse, we find reflections of our own darkest possibilities. With each viewing, new layers of meaning emerge, new details catch the eye, and new interpretations suggest themselves. Like Norman’s troubled psyche, Psycho contains multitudes, rewarding repeated viewings with fresh insights and renewed terror. It stands as a testament to cinema’s power to not just entertain, but to transform our understanding of what it means to be human – and what it means to be afraid.