Everything you need to know about the 1960 classic that changed modern horror and thriller cinema.

Key Facts

| Feature | Detail |

|---|---|

| Release Date | June 16, 1960 (NYC Premiere), Sept 8, 1960 (US wide) |

| Runtime | 109 minutes |

| MPAA Rating | R (originally unrated; rated R since the 1980s) |

| Budget / Gross | ~$800,000 / ~$32 million (1960) |

| Director | Alfred Hitchcock |

| Writers | Joseph Stefano (screenplay), Robert Bloch (novel) |

| Director of Photography | John L. Russell |

| Editor | George Tomasini |

| Music Composer | Bernard Herrmann |

| Format | 35mm Black and White |

| Studio | Shamley Productions / Paramount Pictures |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.85:1 |

Introduction & Overview

Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho didn’t just push boundaries—it obliterated them. Released in 1960 as Hollywood navigated the collapse of the Hays Code and rising competition from international arthouse cinema, this low-budget thriller redefined what American films could show, how stories could be told, and what audiences could endure.

The film’s revolutionary impact begins with its narrative structure. Hitchcock made the audacious decision to kill his apparent protagonist, Marion Crane, just 47 minutes into the film—a twist that left audiences genuinely shocked and disoriented. This wasn’t merely a plot device; it was a fundamental disruption of cinematic grammar that forced viewers to realign their sympathies mid-film, shifting from Marion to her killer, Norman Bates, during the methodical cleanup sequence.

The shower scene itself became cinema’s most analyzed 45 seconds. With 78 camera setups and 52 cuts compressed into less than a minute of screen time, Hitchcock and editor George Tomasini created a masterclass in montage that suggested brutal violence while showing surprisingly little. Bernard Herrmann’s shrieking violin score—those stabbing, descending glissandos—became as iconic as the visuals themselves, transforming the sequence into a full sensory assault.

Hitchcock’s marketing strategy proved equally groundbreaking. His “no one admitted after the start” policy, unprecedented in 1960, transformed moviegoing from a casual drop-in activity to an event. Theater managers were instructed to refuse entry to latecomers—”not even the manager’s brother, the President of the United States, or the Queen of England.” This control extended to an enforced spoiler embargo, with Hitchcock recording personal messages urging audiences not to reveal the ending. The film’s mystery became its primary selling point, establishing the template for thriller marketing that persists today.

Release, Restorations & Home Video

Hitchcock’s release strategy for Psycho broke every Hollywood convention. Self-financing much of the production after Paramount balked at the material, he maintained unprecedented control over distribution and marketing. The film premiered in New York City on June 16, 1960, with only select critics permitted advance screenings. The national rollout in September came wrapped in secrecy—actors were forbidden from giving plot-revealing interviews, promotional materials emphasized mystery over content, and those infamous “no late admission” signs appeared at every theater.

The marketing campaign’s centerpiece was its spoiler protection. Hitchcock filmed a six-minute trailer where he personally toured the Bates house and motel, teasing locations without revealing plot points. Theater lobbies displayed contracts that patrons signed, promising not to reveal the ending. This novelty marketing generated massive curiosity, helping the film gross over $32 million worldwide against its $800,000 budget.

For decades, most viewers saw a slightly censored version of Psycho. International markets and some domestic prints featured small trims to the shower scene and Arbogast’s murder—removing frames that showed the knife entering flesh or glimpses of Janet Leigh’s body. The original “uncut” version, matching Hitchcock’s 1960 theatrical release, wasn’t widely available until 2020’s 4K restoration.

The definitive home video release is the 2020 Universal 4K Ultra HD edition (also available from Arrow Video in the UK). This restoration, sourced from the original camera negative, presents both the theatrical and uncut versions via seamless branching. The 4K scan reveals unprecedented detail in John L. Russell’s cinematography—the sharp contrasts, deep shadows, and that distinctive grainy texture that gives Psycho its documentary-style immediacy.

Filming Locations

Though distributed by Paramount, Psycho was shot primarily at Universal Studios, where Hitchcock’s television crew could work quickly and economically. The Bates house and motel, now among cinema’s most recognizable structures, were cobbled together from recycled studio facades on the Universal backlot.

The Gothic Revival house began as a two-sided shell, with only the front and left side fully constructed for filming. Over subsequent decades, it was expanded into a complete four-sided structure for the sequels and studio tours. The house has been relocated multiple times but currently sits on a hill overlooking Falls Lake—the same artificial pond where Norman sank Marion’s car. Today, it remains a highlight of the Universal Studios Hollywood tram tour, perpetually looming over visitors as one of the park’s most photographed attractions.

The fictional town of Fairvale was created using Universal’s Colonial Street (now Wisteria Lane from Desperate Housewives). The hardware store where Sam Loomis worked was a redressed facade that’s been rebuilt multiple times. Stage 18, where the shower sequence was filmed over seven days, still stands and is occasionally referenced in studio documentation.

For Phoenix establishing shots, Hitchcock sent a second unit to film aerial views of the actual city. The Jefferson Hotel at 101 South Central Avenue (now the Barrister Place Building) served as the location for Marion and Sam’s lunchtime rendezvous. Marion’s highway journey used California’s Highway 99, while the used car lot where she trades vehicles still operates as Century West BMW on Lankershim Boulevard in North Hollywood.

Plot Summary

Psycho begins with a classic noir setup that becomes horrifyingly irrelevant. Marion Crane, a Phoenix real estate secretary, sees an opportunity to escape her dead-end life when a client leaves $40,000 in cash for a property deal. In a moment of desperate impulse, she steals the money and flees toward California, where her lover Sam Loomis runs a struggling hardware store.

The journey unravels Marion’s composure. A suspicious highway patrolman trails her. Her paranoid car trade attracts attention. By nightfall, exhausted and lost after leaving the main highway, she discovers the Bates Motel—a forlorn establishment bypassed by the new interstate. The proprietor, Norman Bates, seems harmlessly awkward, a young man dominated by his invalid mother’s voice echoing from the Gothic house on the hill.

Over sandwiches in Norman’s parlor—surrounded by his taxidermied birds—Marion recognizes her own trap. Norman’s gentle madness and mother fixation mirror her moral crisis. She resolves to return to Phoenix and face the consequences. This redemption comes too late.

While showering, Marion is murdered by a shadowy female figure in the film’s pivotal sequence. Norman, seemingly horrified by his mother’s violence, meticulously erases the crime—mopping blood, wrapping the body in the shower curtain, loading Marion and her belongings into her car’s trunk, and pushing the vehicle into the swamp. The $40,000, unknown to Norman, sinks with the car.

The film’s second movement follows private investigator Milton Arbogast, hired to recover the stolen money. His trail leads to the Bates Motel, where Norman’s nervous evasions confirm Marion’s presence. When Arbogast attempts to question Mrs. Bates, he’s murdered on the staircase—Hitchcock’s camera capturing his backward fall in one of cinema’s most disorienting shots.

The final act brings Marion’s sister Lila and Sam Loomis to investigate both disappearances. While Sam distracts Norman, Lila explores the house, discovering Mrs. Bates’s mummified corpse in the fruit cellar. Norman, dressed as “Mother,” attacks with a knife before Sam subdues him. A psychiatrist’s exposition reveals Norman’s fractured psyche—how he murdered his mother and her lover years ago, then absorbed her personality to cope with matricidal guilt. The film’s final image shows Norman completely subsumed by the “Mother” personality, smiling blankly as Marion’s car is dredged from the swamp.

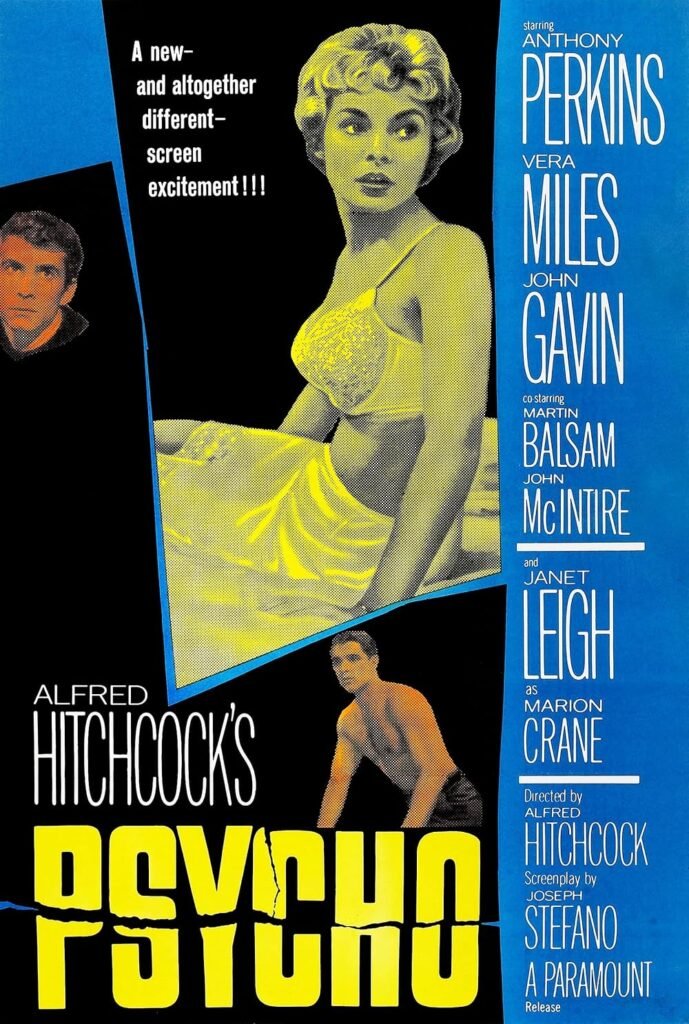

Cast & Characters

Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) stands as one of cinema’s most complex villains, precisely because he doesn’t initially register as one. Perkins plays Norman with disarming vulnerability—stammering, bird-like, boyishly handsome yet somehow incomplete. His performance layers innocence over menace, allowing audiences to sympathize even as evidence mounts. The character’s duality manifests physically: Norman’s nervous tics and hesitant speech patterns contrast with “Mother’s” decisive violence. Perkins makes Norman’s mental fracture feel tragically human rather than monstrous, turning what could have been camp into genuine pathos. The performance established a new archetype—the sympathetic psychopath whose damaged humanity makes their evil more disturbing.

Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) revolutionized the role of the female lead by dying halfway through her own movie. Leigh grounds Marion in recognizable desperation—she’s neither purely virtuous nor villainous, but a woman pushed past her limits by romantic frustration and economic anxiety. Her performance in the parlor scene with Norman is particularly masterful, registering Marion’s growing unease through subtle glances and protective body language. Leigh makes Marion’s moral journey feel authentic, selling both the impulsive theft and the genuine remorse that follows. Her shocking death establishes the template for the horror genre’s relationship with female victims—vulnerable yet resourceful, sympathetic yet expendable.

Lila Crane (Vera Miles) emerges as the film’s true protagonist after Marion’s death, embodying a more forceful female archetype. Unlike the era’s typical supporting female characters, Lila drives the investigation, challenges male authority, and ultimately uncovers the truth. Miles plays her with sharp intelligence and barely contained grief, making Lila’s determination feel personal rather than procedural. She prefigures the “final girl” of later horror films—the survivor who confronts the monster and lives to tell the tale.

Sam Loomis (John Gavin) and Milton Arbogast (Martin Balsam) represent masculine authority gradually stripped of power. Gavin’s Sam begins as Marion’s motivation but becomes increasingly ineffectual, reduced to a distraction while Lila does the real investigating. Balsam’s Arbogast appears supremely confident—the classic private detective who always gets his man—making his abrupt murder all the more destabilizing for audiences expecting noir conventions.

Hitchcock’s genius lies in how he manipulates audience identification throughout. We begin aligned with Marion, sharing her anxiety and guilt. After her death, the film audaciously shifts our sympathy to Norman during the cleanup, making us complicit in covering up the crime. Only gradually do we realign with Lila and Sam, but by then our moral compass has been thoroughly disrupted. We’ve been made voyeurs, accomplices, and ultimately victims of Hitchcock’s narrative trap.

Behind the Scenes

The story originated with Robert Bloch’s 1959 novel, itself inspired by the Ed Gein case that horrified America. Gein, a Wisconsin farmer who killed at least two women and exhumed corpses to create household items from human remains, provided the seed for Norman’s psychological profile. Bloch transformed Gein’s grotesque reality into psychological horror, focusing on the mother-son dynamic that would become Psycho’s dark heart. Hitchcock purchased the novel’s rights for $9,000, using a blind bid to keep his involvement secret and buying up as many copies as possible to preserve the ending’s shock.

Joseph Stefano’s screenplay shifted Bloch’s middle-aged, alcoholic Norman into Anthony Perkins’s boyish incarnation, making the character more sympathetic and the revelation more disturbing. Stefano also expanded Marion’s character, making her flight and moral crisis the film’s emotional anchor before yanking it away.

The Production Code Administration initially rejected the script, citing the opening scene’s implied nudity, the bathroom scenes, and excessive violence. Hitchcock shot everything anyway, then engaged in strategic negotiation—agreeing to trim certain shots if censors would approve others they’d initially rejected but couldn’t quite identify as problematic upon reviewing. The film’s first shot of a flushing toilet became an absurd battlefield, with Hitchcock refusing to cut it. International censors proved harsher—Britain demanded audio and visual cuts to the murders, while some countries banned it entirely.

John L. Russell’s cinematography, honed on Alfred Hitchcock Presents, employed television techniques for cinematic impact. The narrow aspect ratio creates claustrophobia. High contrast lighting turns familiar spaces sinister. The camera becomes predatory—peering through windows, lurking in corners, assuming the killer’s perspective. During the shower scene, Hitchcock and Russell used a custom-built shower with removable walls, allowing for those impossible angles that disorient viewers.

The shower sequence required 78 camera setups over seven days. George Tomasini’s editing creates violence through suggestion—we never see knife penetrating flesh, yet the rapid cuts (averaging one per second) create that impression. The sequence breaks conventional editing rules, with mismatched screen direction and deliberate spatial confusion that mirrors Marion’s disorientation.

Bernard Herrmann’s score, performed by strings alone, abandons melody for texture and rhythm. The shower scene’s “shrieking” violins—played at the extreme top of their range—create an almost physical sensation of stabbing. Herrmann achieved this by having violinists play downward glissandos while applying heavy pressure, creating that distinctive screech. He composed the score against Hitchcock’s initial preference for no music during the murder—the director later called Herrmann’s contribution “33% of the effect.”

Economic constraints shaped aesthetic choices. Hitchcock used his television crew from Alfred Hitchcock Presents, shooting in 30 days for under $1 million. Black and white film stock saved money while creating the stark, documentary look. Chocolate syrup substituted for blood (it photographed better in black and white). A casaba melon provided stabbing sound effects. These budgetary compromises became artistic triumphs—the film’s “cheap” look enhanced its raw, immediate impact.

Themes & Analysis

Voyeurism operates as Psycho’s central metaphor and method. The film opens with a camera that penetrates Phoenix’s skyline, peering through a window at Marion and Sam’s illicit afternoon. This intrusive gaze establishes the audience as voyeurs, a position reinforced when Norman spies on Marion through his peephole—hidden behind a painting of “Susanna and the Elders,” itself about voyeuristic violation. We become complicit in Norman’s watching, sharing his perspective and, disturbingly, his excitement. Hitchcock implicates viewers in the very act of cinema—we pay to watch private moments, violent acts, and psychological dissolution.

The domestic space transforms from sanctuary to trap. The Bates house, that Gothic eruption on the hill, literalizes the Freudian architecture of Norman’s psyche—”Mother” in the superego’s commanding position above, Norman caught between duty and desire at motel level, and the truth buried in the cellar’s unconscious depths. Every domestic space proves false: Marion and Sam’s hotel room enables adultery, the shower becomes a death chamber, and the fruit cellar preserves a mummified matriarchy.

Gender and identity fragment throughout the film. Norman’s cross-dressing isn’t played for shock alone but represents a complete personality dissolution. “Mother” exists as Norman’s projection of maternal authority, sexual repression, and murderous jealousy. Marion, introduced as a sexual being (in bed, in white lingerie), transforms through costume—the black undergarments after the theft, the conservative dress for dinner with Norman, finally the vulnerable nakedness that makes her a victim. The film suggests gender as performance, identity as unstable construction.

Moral boundaries dissolve from the opening frames. Marion’s “theft” feels justified by her circumstances. Norman’s cover-up seems almost reasonable given “Mother’s” violence. The audience shifts allegiances without firm moral ground—we want Marion to escape, then we want Norman to sink her car, then we want Lila to uncover the truth. This moral vertigo reflects post-war American anxiety about authority, sexuality, and social order. The psychiatrist’s final explanation attempts to restore rational order but feels inadequate against the chaos Hitchcock has unleashed.

The film explores repression’s violent return. Norman’s sexual desire, forbidden by “Mother,” explodes in murder. Marion’s repressed desperation manifests in crime. The culture’s repressed discussions of mental illness, sexual dysfunction, and maternal pathology erupt through the screen. Psycho serves as a cultural release valve, allowing audiences to experience forbidden anxieties in the safe darkness of the theater.

Cultural Impact & Legacy

Initial critical reception proved divisive. Bosley Crowther of the New York Times called it “a blot on an honorable career,” while Andrew Sarris championed its formal innovations. Some critics dismissed it as Hitchcock slumming in exploitation. Time vindicated the film’s defenders. By 1992, Psycho topped the Village Voice critics’ poll of the greatest films ever made. The Library of Congress selected it for the National Film Registry in 1992, recognizing its cultural significance. Today, it routinely appears on lists of cinema’s greatest achievements.

The film revolutionized horror grammar. The shower scene established the slasher film’s central mechanism—vulnerable woman, domestic space, sudden violence, and the killer’s perspective shot. Halloween (1978) explicitly homages Psycho—from casting Janet Leigh’s daughter Jamie Lee Curtis to naming the psychiatrist Sam Loomis. Friday the 13th literalizes the vengeful mother. Scream makes the Psycho references explicit, with characters discussing the film while living its patterns.

Italian giallo films absorbed Psycho’s aesthetic wholesale—the black-gloved killer, psychosexual motivation, and elaborate murder sequences all derive from Hitchcock’s template. Directors like Mario Bava and Dario Argento pushed Psycho’s implications toward greater explicitness while maintaining its emphasis on style over coherence.

The shower scene entered cultural consciousness as shared trauma and reference point. It’s been parodied countless times—from Mel Brooks’s High Anxiety to The Simpsons. The house became Universal Studios’ most photographed structure. Bernard Herrmann’s shrieking violins became shorthand for impending violence. “Bates Motel” entered the vernacular as code for anywhere unsavory. Norman Bates became the prototype for sympathetic psychopaths from Hannibal Lecter to Patrick Bateman.

The film transformed how Hollywood approached horror. Before Psycho, horror was B-movie territory—monsters, mad scientists, and gothic castles. Hitchcock proved horror could be profitable, respectable, and contemporary. The genre shifted from external threats to internal dissolution, from castles to suburbs, from monsters to the boy next door. Every psychological thriller owes something to Psycho’s demonstration that the most terrifying monsters look just like us.

Franchise & Influence

The three direct sequels explore different aspects of Norman’s pathology. Psycho II (1983) takes the radical approach of making Norman sympathetic—released after 22 years, he struggles for sanity while others conspire to drive him back to madness. Director Richard Franklin creates genuine suspense about whether Norman or his tormentors pose the real threat. Anthony Perkins’s performance deepens, showing Norman’s self-awareness and desperation for normalcy.

Psycho III (1986), directed by Perkins himself, embraces religious imagery and slasher conventions. A suicidal former nun arrives at the motel, triggering Norman’s Madonna-whore complex. The film adds backstory through flashbacks while ramping up the gore. Psycho IV: The Beginning (1990), a TV movie with flashbacks to Norman’s youth, explores the mother-son relationship’s origins. While competent, these sequels never recapture the original’s shocking impact—how could they, when the original’s power came from shattering innocence?

Gus Van Sant’s 1998 shot-for-shot remake remains cinema’s strangest experiment. Using Stefano’s original script and copying Hitchcock’s camera angles, Van Sant created a color Psycho with contemporary stars (Vince Vaughn, Anne Heche, Julianne Moore). The film failed critically and commercially, but its very existence proves illuminating. By demonstrating that identical shots don’t create identical effects, the remake highlighted how much of Psycho’s power came from its historical context, the black-and-white aesthetic, and Perkins’s irreplaceable performance.

The A&E/Universal series Bates Motel (2013-2017) reimagined the story as contemporary tragedy. Set in present-day Oregon, the show explores Norman’s adolescence as his psychosis develops. Freddie Highmore’s Norman feels genuinely dangerous yet pitiable. Vera Farmiga’s Norma Bates emerges as complex and sympathetic rather than simply monstrous. The series expands Psycho’s mythology while respecting its themes—identity, repression, and the American family’s dark underbelly.

Beyond official sequels, Psycho’s influence spreads everywhere. Brian De Palma built his career on Hitchcockian variations—Dressed to Kill and Body Double explicitly rework Psycho’s themes. The found-footage horror of Paranormal Activity owes its domestic terror to Hitchcock’s demonstration that home provides no safety. Prestige television from Twin Peaks to Hannibal explores the sympathetic psychopath archetype Norman originated. Every twist that kills a protagonist mid-story, every shower scene that makes bathing nervous, every creepy motel on a lonely highway—they all lead back to that house on the Universal hill.

Viewing Guide

The definitive viewing experience requires the 2020 4K Ultra HD release from Universal or Arrow Video. These editions present both the theatrical and uncut versions, though differences are minimal—a few frames of knife contact, slightly extended glimpses of flesh. The 4K restoration from the original negative reveals details invisible on previous releases: the texture of the wallpaper in Marion’s room, the dust motes in Norman’s parlor, the gradations of shadow in the cellar. Watch on the largest screen possible to appreciate the compositional precision.

Pay attention to Hitchcock’s manipulation of perspective. Notice how the camera assumes different characters’ viewpoints—Marion’s anxiety, Norman’s voyeurism, Lila’s investigation—making you complicit in each position. Watch for the recurring imagery of eyes and birds, the visual motifs that link watching with predation. The famous shots—through the shower curtain, down the drain, into Norman’s eye—work because of careful preparation through earlier, subtler compositions.

Listen to how Herrmann’s score operates. Beyond the famous shower cue, notice how the music bridges scenes, creates unease through repetition, and sometimes drops out entirely for maximum impact. The absence of music during Norman and Marion’s parlor conversation makes their dialogue feel naked, vulnerable.

Study the editing patterns. The film alternates between long takes that build tension and rapid montages that release it explosively. The shower scene’s fragmentation contrasts with the methodical single takes of Norman’s cleanup. Arbogast’s death mixes both—the long climb up the stairs interrupted by violent cuts.

For double features, pair Psycho with Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Les Diaboliques (1955), which inspired Hitchcock’s interest in shocking his audience. Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960), released the same year, offers a British perspective on voyeurism and violence. For influence, watch Halloween (1978) to see how John Carpenter transformed Hitchcock’s innovations into modern slasher conventions. Roman Polanski’s Repulsion (1965) takes Psycho’s psychological dissolution into surrealist territory.

Contemporary viewers should approach Psycho understanding its original context—when married couples on television slept in separate beds, when film violence meant cowboys clutching their stomachs, when toilets never appeared on screen. The film’s transgressions have been so thoroughly absorbed that its shock value requires historical imagination.

FAQs

Was chocolate syrup really used for blood in the shower scene? Yes, Hershey’s chocolate syrup served as blood throughout the shower sequence. Hitchcock and his crew discovered that chocolate syrup’s consistency and darkness photographed more convincingly than stage blood in black and white. The syrup’s viscosity allowed it to run slowly down the drain, creating that hypnotic spiral that dissolves to Marion’s dead eye. Makeup artist Jack Barron confirmed they went through several bottles during the week-long shoot.

How many cuts are in the shower scene? The 45-second sequence contains 52 cuts utilizing 78 different camera angles. Editor George Tomasini and Hitchcock spent a full week assembling the sequence, timing each cut to Herman’s staccato score. The rapid editing creates an impression of violence while showing minimal actual contact—we never see the knife penetrate flesh, yet audiences swore they did. This editorial violence influenced every action film that followed.

Was Norman Bates based on a real killer? Robert Bloch drew inspiration from Ed Gein, the Wisconsin murderer whose crimes shocked America in 1957. Gein killed at least two women and exhumed graves to create masks and furniture from human remains. However, Norman differs significantly from Gein—younger, more attractive, and sympathetic where Gein was simply monstrous. Bloch used Gein as a starting point for exploring how an seemingly ordinary person could harbor such darkness. Screenwriter Stefano knew nothing of the Gein connection when adapting the novel, creating Norman’s character from psychological rather than true-crime sources.

Why was Psycho shot in black and white? Multiple factors influenced this choice. Budget constraints made black and white film stock more economical—crucial for Hitchcock’s self-financed production. Artistically, black and white created the stark, documentary aesthetic that makes the film feel immediate and real. Practically, it allowed Hitchcock to sidestep censorship concerns about gore—chocolate syrup looked like blood, but blood would have triggered stronger censorship. The monochrome photography also enhanced the film’s noir atmosphere and psychological themes through high contrast and deep shadows. Hitchcock later claimed he couldn’t have achieved the same effect in color.

Conclusion

Psycho endures because it remains dangerous. Sixty-four years after audiences first screamed at Janet Leigh’s murder, the film still unsettles through its fundamental rupture of narrative security. Hitchcock didn’t just kill his protagonist—he killed the contract between filmmaker and audience that promised certain securities, certain structures, certain sanctuaries.

The film’s true horror lies not in Norman’s knife but in its systematic violation of safe spaces: the shower, the staircase, the bedroom, the family home. Every contemporary horror film that makes us nervous about mundane domestic spaces owes that anxiety to Hitchcock’s demonstration that nowhere is safe, not even the movies themselves.

Modern viewers, raised on films that learned Psycho’s lessons, might miss its original impact. But watch it properly—in high definition, in darkness, with attention to craft—and its power persists. The shower scene still jolts. Norman’s smile still chills. That house still looms. Psycho remains what Hitchcock intended: pure cinema, using every tool of the medium to manipulate, disturb, and ultimately thrill audiences willing to submit to its dark magic.