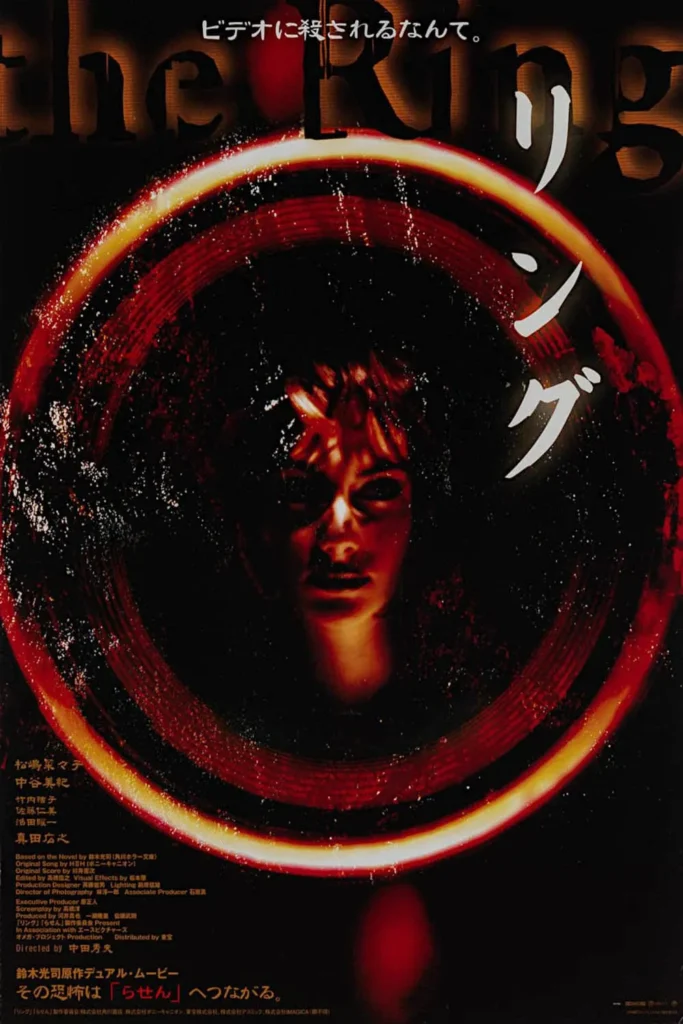

Ringu crawls through your mind like a shadow across water, a horror film that doesn’t just scare – it infects. In 1998, director Hideo Nakata unleashed something primordial onto unsuspecting audiences, a terror that seeps into your bones and makes its home there, whispering promises of death in seven days.

Let me paint you a picture of my first viewing: Rain hammering against windows, the soft hum of a television set, and that cursed tape beginning to play. The images flash across the screen like fever dreams – a woman combing her hair, an eye that seems to peer into your soul, a well that holds secrets darker than its depths. This isn’t just a movie – it’s a transmission from our collective nightmares, a visual poem written in the language of fear. The first time I witnessed these fragments of madness, I found myself unable to look away, even as every instinct screamed for me to stop watching.

This is where Nakata proves himself a master of psychological warfare. The curse spreads through technology, turning our everyday comfort – the television – into a portal for ancient vengeance. Each frame is composed with the precision of a death sentence, washing scenes in ghostly blues and greys that make even daylight feel like twilight. The director understands that true horror lives in the spaces between breaths, in the static-filled silence before the phone rings. Every shadow becomes a potential threat, every reflection a possible glimpse of something that shouldn’t be there.

Nanako Matsushima’s Reiko Asakawa isn’t your typical horror protagonist – she’s a journalist, a mother, a woman racing against time while carrying the weight of a curse. Her performance is a masterclass in controlled desperation, each discovery peeling back another layer of mystery while the clock ticks mercilessly forward. Hiroyuki Sanada brings a wounded intensity to Ryuji, her ex-husband and reluctant partner in this dance with death. Their relationship feels lived-in, complicated, real – making the stakes all the higher as they dive deeper into the abyss. The way they navigate their past while facing an uncertain future adds a layer of emotional complexity rarely seen in horror films.

But let’s talk about Sadako. Sweet, vengeful Sadako. She’s not just another ghost in a white dress – she’s an avatar of rage, a victim turned vengeful spirit whose very existence challenges the boundary between technology and terror. That scene – you know the one – where she emerges from the television screen, is quite possibly one of the most perfectly crafted moments in horror history. It’s primal. Visceral. The way she moves, jerky and inhuman, her hair hanging like a death shroud – it taps into something ancient in our lizard brains that screams “run.” I remember watching this scene through splayed fingers, my heart threatening to burst from my chest.

The genius of Ringu lies in its fusion of modern anxiety with ancient Japanese folklore. The yurei tradition meets the digital age, creating something entirely new yet deeply rooted in cultural fear. The curse spreads like a virus, each viewing creating new carriers, a metaphor that feels especially prescient in our age of viral content and digital contagion. The film explores the intersection of traditional Japanese ghost stories and contemporary fears about technology’s invasive presence in our lives.

Nakata’s direction is precise, patient, methodical – like Sadako herself, taking exactly seven days to claim her victims. The film builds tension like a master violinist drawing out a single note until it threatens to snap. The investigation unfolds like a nightmare logic puzzle, each piece revealing new horrors while the deadline looms ever closer. The way he frames his shots creates a constant sense of unease – empty corridors stretch into darkness, televisions loom like monoliths in dim rooms, and every reflective surface becomes a potential portal for horror.

The sound design deserves special mention – the way it uses silence as a weapon, punctuated by the harsh ring of a telephone or the static hiss of a television. It’s minimalist yet devastating, creating an atmosphere of creeping dread that wraps around you like a cold, wet blanket. The audio landscape is carefully crafted to keep viewers on edge, with subtle environmental sounds that make even quiet moments feel threatening.

What makes Ringu truly extraordinary is its understanding of horror’s deepest truth – that the most terrifying things are those that follow rules. The curse is methodical: watch the tape, receive the call, die in seven days. It’s this very predictability that makes it so frightening. There’s no negotiating with it, no hoping it might pass you by. It’s coming, as surely as the tide, as inevitably as death itself. This mechanical nature of the curse adds a layer of existential dread that few horror films achieve.

The film’s commentary on technology feels more relevant now than ever. The videotape acts as a vessel for ancient hatred, a modern medium carrying an age-old curse. It speaks to our fear of technology as a conduit for forces beyond our understanding or control. The television screen becomes a membrane between our world and something darker, something waiting to reach through and drag us under. In our current age of smartphones and social media, this fear of technology as a vector for malevolent forces resonates even more strongly.

The climax, with its revelation about the nature of the curse and its perpetuation, is a masterstroke of horror storytelling. The only way to survive is to make someone else watch the tape – to pass the curse along like a chain letter written in blood. It’s a moral nightmare that forces us to confront what we’d be willing to do to save ourselves or those we love. This ethical dilemma elevates the film beyond simple horror into something more philosophically challenging.

Ringu spawned countless imitators and a successful American remake, but none have matched its pure, distilled terror. This is horror that respects its audience, that takes its time, that understands fear is as much about anticipation as revelation. It’s a film that changed the landscape of horror cinema, proving that the genre could be both intellectually stimulating and viscerally terrifying. Its influence can be seen in countless films that followed, though few achieve its perfect balance of psychological terror and supernatural horror.

Years later, what lingers isn’t just Sadako’s crawl from the television – it’s the quiet moments. The dripping of water. The flash of a distorted face in a photograph. The soft static of a television set late at night. Ringu taps into something fundamental about human fear – our terror of the inevitable, our dread of watching the clock wind down to zero, our horror at being forced to choose between our survival and our humanity. Those images have burned themselves into my psyche, making me hesitate every time I hear an unexpected phone ring or catch a glimpse of static on a screen.

This is a film that doesn’t just show you horror – it makes you complicit in it. Every viewing adds another link to the curse’s chain, spreading like ripples in a well of darkness. It’s a masterpiece of psychological terror that proves the most effective horror isn’t about what you see, but what you know is coming. The way it transforms mundane objects and everyday technology into sources of terror is a testament to its psychological sophistication.

In the end, Ringu isn’t just a ghost story – it’s a dark mirror reflecting our relationship with technology, our fear of the unknown, and the price we’re willing to pay for survival. It’s a film that understands horror isn’t just about making you jump – it’s about making you think, making you feel, making you dread. And in that, it succeeds brilliantly, leaving behind a legacy as enduring as Sadako’s curse itself. It stands as a testament to the power of horror cinema to tap into our deepest fears and transform them into art that haunts us long after the credits roll.