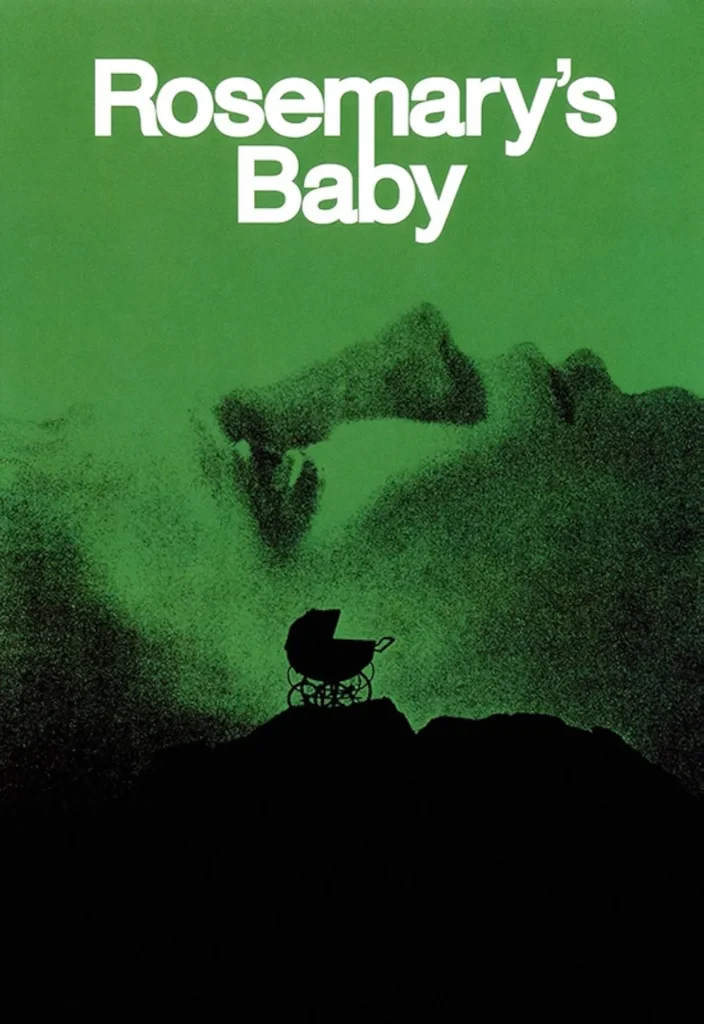

Rosemary’s Baby from 1968 teaches us the level of evil that lurks in the darkest depths of hell. The devil doesn’t arrive with hellfire and brimstone. He creeps in through your neighbor’s door, bearing chocolate mousse and herbs, wearing the mask of maternal concern. In Roman Polanski’s masterwork of paranoid terror, Satan himself is just another New York City neighbor, and hell is a Gothic apartment building on the Upper West Side.

Rosemary’s Baby (1968) writhes beneath your skin like a parasite, a slow-burning nightmare that transforms pregnancy into a prison sentence and motherhood into a pact with darkness. The film burrows deep into our collective fears about body autonomy, trust, and the monstrous potential lurking behind every smile.

Mia Farrow’s Rosemary Woodhouse floats through the Bramford’s shadowy halls like a ghost caught between worlds. Her pixie cut and mod fashion choices scream youth and vitality, but watch as the life drains from her eyes, frame by frame, her body becoming a vessel for forces beyond her comprehension. Farrow doesn’t just act – she decomposes on screen, her transformation from bright-eyed newlywed to hollow-cheeked prisoner of her own pregnancy is a descent into hell measured in subtle glances and trembling hands.

The horror here isn’t in the jump scares or gore – it’s in the steady erosion of reality, the way sanity slips through your fingers like grains of sand. Polanski orchestrates this descent with surgical precision. Every seemingly innocent interaction – a cup of tea, a friendly visit, a doctor’s appointment – becomes loaded with menace. The Bramford itself looms like a mausoleum of broken dreams, its Gothic architecture a cage of stone and shadow where hope goes to die.

John Cassavetes brings a reptilian charm to Guy Woodhouse, Rosemary’s ambitious actor husband. His performance is a masterclass in subtle betrayal, each loving gesture masking a calculation, every embrace tainted by his Faustian bargain. When he tells Rosemary he’s traded his wife’s womb to Satan for a Broadway role, the real horror isn’t in the revelation – it’s in how mundane the transaction feels, like selling a used car or trading stock options.

Ruth Gordon’s Minnie Castevet deserves special mention – she’s the devil’s own yenta, serving evil with a side of chicken soup and motherly advice. Her performance won an Oscar, and rightfully so. She embodies the banality of evil, making witchcraft feel as commonplace as a bridge club meeting. Sidney Blackmer’s Roman Castevet completes this unholy duo, his cultured manner and paternal warmth making him all the more terrifying when the mask finally drops.

The film’s infamous rape scene – a hallucinatory nightmare of ritual abuse – remains one of cinema’s most disturbing sequences. Polanski stages it like a fever dream, blending Catholic imagery with pagan ritual, making the violation of Rosemary’s body feel both intensely personal and cosmically significant. The scene works because it taps into primal fears about violation, control, and the horror of being conscious while powerless.

But the true genius of Rosemary’s Baby lies in its subversion of the domestic sphere. Every safety net becomes a trap: medicine becomes poison, neighbors become conspirators, husband becomes betrayer. The film ruthlessly strips away every support system until Rosemary stands alone, her paranoia proven horrifically justified. In this way, it’s a perfect reflection of its era – the late 1960s’ collapse of trust in institutions, the emerging feminist consciousness, the fear that the American Dream itself might be a gilded cage.

Polanski’s direction is a masterwork of restraint. He builds tension through composition and implication rather than cheap scares. Watch how he frames Rosemary in doorways and mirrors, always slightly off-center, suggesting a world permanently tilted off its axis. The camera becomes increasingly intrusive as the film progresses, mirroring the violation of Rosemary’s body and mind.

The sound design deserves special mention – Krzysztof Komeda’s lullaby theme is a siren song of innocence corrupted, its childlike melody becoming more sinister with each reprise. The film’s use of silence is equally effective, making every creak of the Bramford’s ancient floors feel like a warning bell.

What elevates Rosemary’s Baby above mere horror is its savage critique of patriarchal control. Every man in Rosemary’s life – her husband, her doctor, even her previous protector Hutch – either betrays her or fails her. The film becomes a damning indictment of how society gaslights women, dismissing their concerns as hysteria while literally conspiring to control their bodies.

The ending remains one of cinema’s most disturbing conclusions, not for its revelation of Satan’s spawn, but for what it says about the power of maternal instinct and the compromises we make to survive. When Rosemary approaches the black bassinet, her choice to mother the devil’s child feels less like surrender and more like a final act of defiance – claiming ownership over the very thing meant to destroy her.

This is a film that understands true horror lies not in the supernatural, but in the ordinary betrayals we suffer at the hands of those we trust. It’s about the terror of being right when everyone tells you you’re wrong, the horror of watching your body become a battlefield for forces beyond your control, the nightmare of realizing that sometimes the devil’s greatest trick isn’t convincing you he doesn’t exist – it’s making you invite him in for dinner.

Fifty-five years later, Rosemary’s Baby remains a razor-sharp dissection of gender politics, bodily autonomy, and the price of ambition. In an era where women’s reproductive rights are still battlegrounds and gaslighting has entered common parlance, its horrors feel more relevant than ever. It’s a testament to Polanski’s vision that the film’s most disturbing aspects aren’t its supernatural elements, but its clear-eyed portrayal of how easily society can conspire to strip a woman of her agency, her sanity, and ultimately, her humanity.

In the end, Rosemary’s Baby isn’t just a horror film – it’s a prophecy, a warning, and a mirror held up to society’s darkest impulses. It shows us that sometimes the scariest monsters aren’t the ones with cloven hooves and burning eyes, but the ones who smile and offer to hold your hand while they lead you straight to hell.

The final shot of Rosemary peering into that black bassinet isn’t just the culmination of her journey – it’s an image that burns itself into your psyche, forcing you to question every assumption about trust, love, and the prices we pay for belonging. In the end, maybe the real horror isn’t that Satan’s son was born – it’s that in a world like ours, his arrival feels almost inevitable.