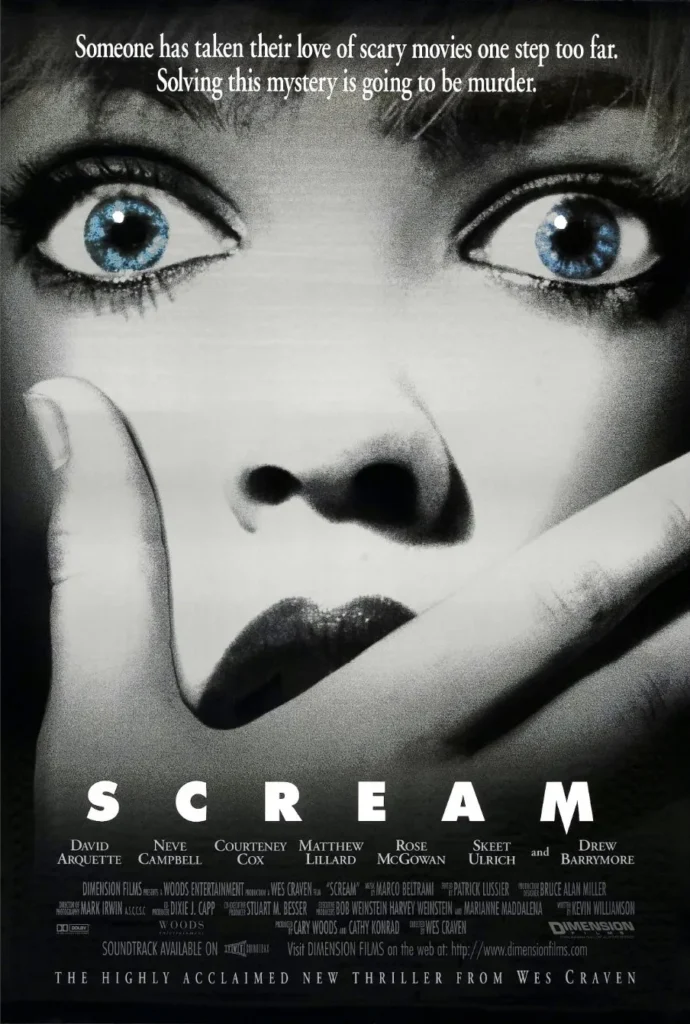

You know that film Scream From 1996? The phone rings in suburban darkness, and just like that, we’re dragged into hell. Not the fire-and-brimstone kind, but something far worse – the kind that lives next door, wears a familiar face, and knows exactly which psychological buttons to push until your sanity splinters like cheap glass.

Wes Craven’s “Scream” doesn’t just slice through the conventions of horror cinema – it performs full psychological surgery on them, leaving us to pick through the exposed bones and sinew of a genre we thought we knew. This isn’t just another tale of teenage terror; it’s a blood-soaked love letter to horror itself, written in the ink of genuine fear and sealed with a twisted kiss.

The opening sequence hits like a uppercut to the solar plexus. Drew Barrymore’s Casey Becker – America’s sweetheart turned sacrificial lamb – plays a game of cinematic trivia where wrong answers are paid for in blood. It’s a masterclass in tension, a cruel joke where the punchline is death, and it sets the stage for something we’ve never seen before: a slasher film that knows it’s a slasher film, and isn’t afraid to dance in the crimson spray of its own self-awareness.

At the heart of this nightmare carnival stands Sidney Prescott (Neve Campbell), a final girl who refuses to play by the rules. She’s not some wide-eyed innocent stumbling through the dark – she’s a warrior forged in the fires of previous trauma, carrying the weight of her mother’s murder like a bullet lodged too close to the heart to remove. Campbell brings a raw authenticity to Sidney that transcends the typical scream queen archetype. Her pain isn’t performative; it’s a living thing that breathes and bleeds through every frame.

The killer – or should I say killers – wear the now-iconic Ghostface mask, a twisted piece of Halloween store plastic that somehow manages to be more terrifying than any supernatural monster. There’s something profoundly disturbing about its blank expression, a void that reflects our own darkness back at us. When it appears, usually accompanied by that bone-chilling voice on the phone, it’s like death itself decided to play a game of cat and mouse.

But what elevates “Scream” beyond mere slaughter is its razor-sharp script by Kevin Williamson. This is meta-commentary that draws blood. Through the character of Randy Meeks (Jamie Kennedy) – our horror-obsessed prophet of doom – the film dissects the very rules it simultaneously follows and breaks. It’s like watching a magician explain their tricks while still managing to fool you completely.

The violence, when it comes, is brutal and unforgiving. Craven, that mad maestro of terror, stages each death with the precision of a conductor leading a symphony of screams. The garage door scene with Tatum (Rose McGowan) is particularly savage – a perfect example of how the film takes familiar suburban objects and transforms them into instruments of destruction. This isn’t just murder; it’s performance art with a body count.

What makes “Scream” truly revolutionary is how it taps into the collective unconscious of a generation raised on horror films. It understands that by the 1990s, we’d seen it all – the summer camps, the babysitters, the final girls. So instead of trying to reinvent the wheel, it straps rockets to it and sends it screaming into the stratosphere. The killers aren’t supernatural entities or masked giants – they’re movie buffs gone wrong, toxic fandom taken to its logical, bloodsoaked conclusion.

Billy Loomis (Skeet Ulrich) and Stu Macher (Matthew Lillard) emerge as perfect villains for this brave new world of meta-horror. Their motivations – a cocktail of mommy issues, movie obsession, and pure psychotic glee – feel disturbingly plausible. They’re not just killing people; they’re directing their own real-life horror film, complete with a third act reveal that would make Hitchcock proud.

Courteney Cox’s Gale Weathers adds another layer of commentary as the ambitious reporter who becomes part of the story she’s covering. Her presence speaks to our cultural obsession with true crime, the way we turn real tragedy into entertainment. The film doesn’t just acknowledge this tendency – it grabs it by the throat and forces us to look at our own complicity.

The technical aspects deserve their own blood-stained spotlight. The cinematography by Mark Irwin turns suburban Woodsboro into a hunting ground where shadows hold secrets and every corner could hide death. Marco Beltrami’s score punctuates the terror with orchestral stabs that feel like ice picks to the base of the skull.

As the body count rises and the mystery unravels, “Scream” maintains its delicate balance between horror and commentary, never letting one overwhelm the other. It’s like watching a tightrope walker traverse a razor wire – the tension comes not just from the possibility of failure, but from the absolute certainty that blood will be spilled either way.

Twenty-five years later, “Scream” still cuts deep because it understands something fundamental about horror: the best monsters are the ones we create ourselves. In an era of endless sequels and reboots, it stands as a testament to what happens when filmmakers trust their audience enough to play with their expectations while still delivering the primal thrills they came for.

This isn’t just a movie about a killer in a ghost mask – it’s about the masks we all wear, the stories we tell ourselves, and the thin line between entertainment and exploitation. It’s a film that forces us to question why we love horror even as it reminds us exactly why we do. Like the best nightmares, it leaves us changed, more aware of the darkness that lurks behind familiar faces, and perhaps a little more careful about answering late-night phone calls.

But what truly haunts me, even after countless viewings, is the way “Scream” captures the claustrophobic terror of small-town life. Woodsboro feels like a pressure cooker of secrets and lies, where everyone knows everyone else’s business, yet nobody sees the killers hiding in plain sight. The film’s atmosphere is thick with paranoia, each scene dripping with the kind of tension that makes your skin crawl and your nerves dance.

There’s something particularly brilliant about the way Craven handles the party sequence in the third act. The sprawling house becomes a maze of death, each room a potential dead end, each friend a potential killer. It’s here that the film’s themes of trust and betrayal reach their bloody crescendo. The reveal of Billy and Stu as the killers still hits like a sledgehammer to the chest – not because it’s unexpected, but because of how perfectly it encapsulates the film’s central idea that evil often wears a familiar face.

In the end, “Scream” isn’t just a slasher film – it’s a mirror held up to our own obsession with violence and voyeurism, reflecting back something both terrible and true. It’s a masterpiece that manages to simultaneously honor and transcend its genre, leaving us with one final, blood-chilling question: what’s your favorite scary movie?