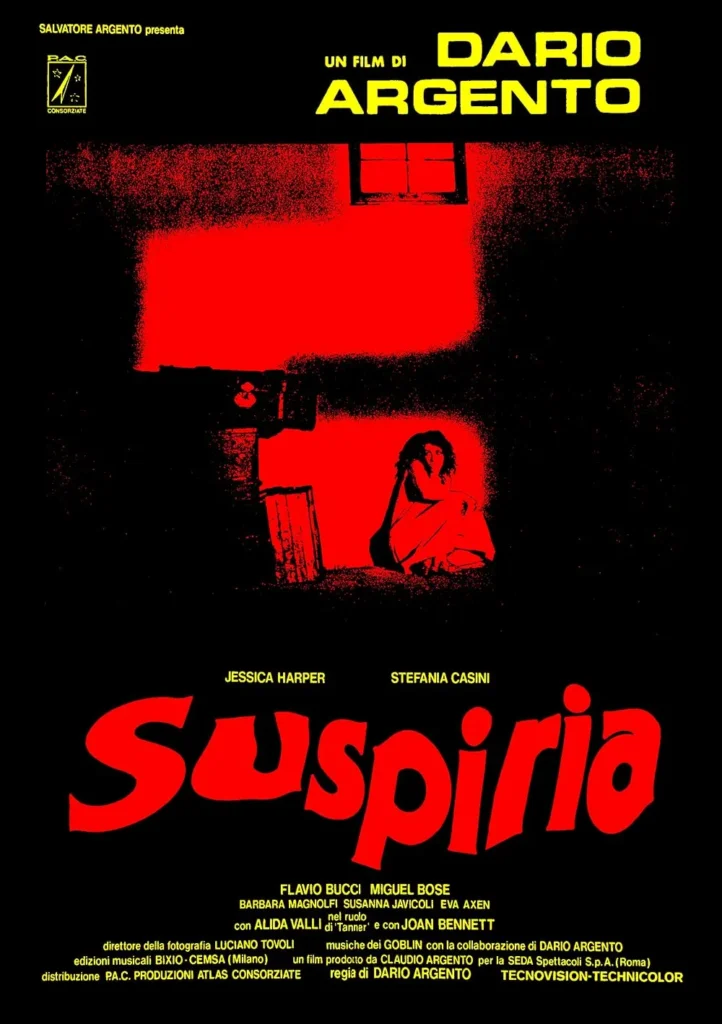

Suspiria 1977 tears through the fabric of reality like a razor through silk, leaving behind a tapestry of blood-soaked dreams that haunt the corners of cinema history. Dario Argento’s masterpiece doesn’t just push boundaries – it shatters them with a primal scream that echoes through decades of horror filmmaking. This isn’t just a movie; it’s a fever dream captured in Technicolor, a witch’s spell cast in cellophane and shadow.

From the moment Jessica Harper’s Suzy Bannion steps into that torrential German downpour, we’re pulled into a world where logic dissolves like sugar in rain. The Tanz Dance Academy looms before us, a creature of brick and mortal waiting to devour its prey. The architecture itself seems to breathe, each corridor and corner hiding secrets that whisper of ancient evils.

The violence, when it comes, arrives like lightning – sudden, brutal, and beautiful in its terrible precision. The film’s opening murder sequence stands as one of horror cinema’s most audacious symphonies of terror. Patricia Hingle’s death dance through stained glass and razor wire transforms murder into macabre art, her blood painting patterns that would make Jackson Pollock weep. It’s a statement of intent: this isn’t just another horror film, it’s a descent into beautiful madness.

Argento orchestrates his terror with the precision of a maestro conducting his darkest symphony. Every frame bleeds color – deep crimsons, electric blues, and venomous greens pulse through the screen like toxic blood through dying veins. The director understood something fundamental about fear: it’s not just about what lurks in darkness, but what hides in plain sight, screaming at us in technicolor glory. The academy’s walls don’t just hide evil; they amplify it, reflect it, make it dance in mirrors until we can’t tell reality from nightmare.

At the heart of this kaleidoscopic nightmare stands Suzy Bannion, our Alice tumbling down a rabbit hole lined with razor blades. Harper brings a vulnerable strength to the role, her wide-eyed innocence gradually hardening into determined survival as she peels back layers of ancient evil. Her journey from dance student to witch-slayer isn’t just about survival – it’s about power, about claiming agency in a world designed to strip it away.

The film’s sound design, anchored by Goblin’s revolutionary score, deserves its own chapter in the annals of horror history. The music doesn’t just accompany the action – it possesses it. Whispered incantations, tribal drums, and demonic synthesizers create a sonic landscape that burrows into your brain like a parasitic worm, laying eggs of dread that hatch when you least expect them. The score doesn’t follow the action; it leads it, dragging us by our ears through each new circle of this technicolor hell.

What sets Suspiria apart from its contemporaries is its commitment to pure, unfiltered nightmare logic. The plot, with its tale of an ancient witch’s coven operating behind the façade of a dance academy, serves merely as a skeleton upon which Argento hangs his tapestry of terrors. This isn’t a film that wants to make sense – it wants to make you feel, to bypass your rational mind and punch you straight in the lizard brain where your oldest fears live.

The dance academy itself becomes a character, its baroque architecture a maze of dangerous beauty. Every room holds the potential for death, every doorway might lead to damnation. The set design creates a space that exists somewhere between reality and nightmare, where the laws of physics seem optional and gravity feels more like a suggestion than a rule.

The supporting cast fills out this twisted fairy tale with performances that straddle the line between reality and grand guignol excess. Alida Valli’s Miss Tanner moves through the academy like a shark in human skin, while Joan Bennett’s Madame Blanc embodies a more subtle kind of evil – the kind that serves tea while planning your murder. These aren’t just characters; they’re archetypes pulled from our collective nightmares and given flesh.

But it’s Helena Markos – the invisible witch queen at the heart of this darkness – who represents the film’s ultimate horror. Her presence infects every frame like a virus, her raspy breathing echoing through the academy’s halls like death’s own lullaby. When Suzy finally confronts this ancient evil, the scene plays out like a fever dream’s climax, reality dissolving completely into a phantasmagoria of violence and vindication.

The violence in Suspiria isn’t just shocking – it’s transformative. Each death scene is choreographed like a ballet, each splash of blood carefully placed like brush strokes on a canvas. The infamous wire room sequence remains one of horror cinema’s most beautiful atrocities, a perfect marriage of visual excess and visceral impact. Argento understood that true horror isn’t just about the act of violence, but about the anticipation, the build-up, the terrible beauty of the inevitable.

What makes Suspiria endure isn’t just its technical brilliance or its innovative approach to horror. It’s the way the film taps into something primordial in our collective unconscious. This is a fairy tale for adults, a warning about the price of knowledge and the cost of power. It’s about the moment when innocence confronts evil and discovers that the only way to survive is to become something new, something dangerous.

The film’s final sequence, as Suzy flees the burning academy with a cryptic smile playing across her lips, leaves us with questions that haunt long after the credits roll. Has she truly escaped, or has she simply inherited the mantle of power she sought to destroy? The smile suggests knowledge – dangerous knowledge – and reminds us that sometimes the price of surviving our nightmares is becoming something that others fear.

Forty-plus years later, Suspiria remains an unmatched achievement in horror cinema. It’s a film that doesn’t just show us nightmares – it teaches us their grammar, their syntax, their terrible poetry. It stands as proof that horror can be high art, that fear can be beautiful, and that sometimes the most terrifying stories are the ones that make the least sense to our waking minds.

In the end, Suspiria isn’t just a horror film – it’s a testament to cinema’s power to create new realities, to bypass our rational defenses and speak directly to our deepest fears and desires. It’s a dream captured on film, a nightmare preserved in amber, a spell that continues to enchant and terrify audiences decades after its first casting. To watch it is to surrender to its power, to allow yourself to be swept away by its terrible beauty, and to emerge changed on the other side.

Modern horror filmmakers still mine this film for inspiration, but none have quite captured its particular magic. Suspiria remains singular – a perfect storm of vision, execution, and audacity that changed what was possible in horror cinema. It’s not just a masterpiece of horror; it’s a masterpiece, period – a work of art that happens to traffic in terror, a beautiful nightmare that we can’t help but return to, again and again, like moths to a crimson flame.