I still remember the first time I watched The Silence of the Lambs. Alone. Past midnight. The kind of silence where you can hear your own pulse in your ears. In the cold fluorescent halls of a maximum security asylum, evil wears a pressed prison uniform and speaks in measured, cultured tones about Dante. My hands gripped the armrests. Waiting. Watching. The film isn’t just a masterpiece of psychological horror – it’s a descent into the darkest corners of human nature, where monsters wear human faces and salvation comes at the cost of your soul.

Jonathan Demme’s 1991 opus opens not with screams but with heavy breathing, as FBI trainee Clarice Starling runs an obstacle course through misty woods. The air feels thick with menace. Watch closely. Something’s hunting. This seemingly innocuous scene sets the tone for what’s to come – a young woman navigating treacherous terrain, always being watched, always being pursued. The film transforms into a savage ballet between predator and prey, with Starling caught between two apex predators: the imprisoned cannibal Dr. Hannibal Lecter and the active killer Buffalo Bill.

Jodie Foster embodies Starling with a raw vulnerability that bleeds through her professional facade. Her West Virginia accent thickens when she’s stressed, her small frame seems to shrink in rooms full of towering men, yet her eyes burn with determination. Every time she steps into that dungeon-like corridor to face Lecter, I feel my own breath catch. Foster doesn’t just play Starling – she channels the quiet desperation of every woman who’s ever felt like prey.

And then there’s Anthony Hopkins as Hannibal Lecter. Stop. Listen. He barely moves. Barely blinks. A statue of malevolence dressed in institutional beige. Hopkins delivers a performance so terrifying it redefined screen villains forever. My skin crawls every time he fixes that unblinking stare on Clarice. His voice is soft, almost gentle, making his sudden explosions of violence all the more shocking. When he describes eating a census taker’s liver “with some fava beans and a nice Chianti,” the casual refinement in his tone turns your stomach more than any graphic violence could. The sound of that hiss after the word “Chianti” – it haunts my dreams.

The genius of the film lies in how it makes us complicit in Lecter’s seduction of Clarice. We lean in close during their verbal sparring matches, transfixed by his insights even as we recoil from his crimes. Their conversations are intimate dances of power and vulnerability, with knowledge and trauma traded like precious currency. “Quid pro quo, Clarice” becomes more than just a phrase – it’s the dark bargain at the heart of the film. How much of yourself are you willing to trade to catch a killer?

Ted Levine’s Buffalo Bill provides the raw, unvarnished counterpoint to Lecter’s sophisticated evil. His basement lair still gives me nightmares – the dank, moldering walls weeping with moisture, the suffocating darkness broken only by the buzz of dying fluorescent bulbs, the pit with its bucket of lotion and desperate screams echoing off concrete. The stench of death and decay mingles with the musty sweetness of moth cocoons. When he stalks Clarice through the dark wearing night vision goggles, I find myself holding my breath, heart hammering against my ribs. His sing-song “Would you fuck me? I’d fuck me” slithers through the darkness like a serpent.

Demme’s direction is masterful in its restraint. He understands that suggestion is more powerful than showing, that anticipation cuts deeper than action. His use of extreme close-ups during the Lecter-Starling conversations creates an unsettling intimacy – we’re too close, invasion of personal space becoming visual metaphor. The camera lingers on faces just a beat too long, making us squirm. When violence erupts, it’s swift and brutal, leaving psychological welts rather than just shock value.

The film’s sound design deserves special mention – the way silence becomes a character itself, punctuated by the click of heels on concrete, the hiss of Lecter’s breath, the flutter of moth wings. Howard Shore’s score creeps like shadows at the edge of consciousness, building tension without ever overwhelming the natural soundscape. Even now, certain notes from that score can send ice water down my spine.

What elevates The Silence of the Lambs above mere thriller status is its unflinching exploration of power dynamics. Every interaction is a negotiation, whether it’s Clarice navigating the male-dominated FBI, Lecter manipulating his captors, or Buffalo Bill exercising ultimate control over his victims. The film forces us to confront uncomfortable truths about authority, gender, and the masks we wear to hide our true natures.

Perhaps most disturbing is how the film makes us question our own moral compass. We find ourselves rooting for Lecter’s escape, even knowing what he is, what he’ll do. When he follows Dr. Chilton through those sun-drenched Caribbean streets in the final scene, I feel that familiar twist in my gut – part revulsion, part dark triumph. The devil we know has won his freedom, and part of us celebrates while our conscience screams in protest.

The technical mastery on display still astounds after countless viewings. Take the way Demme uses his camera to create unease – characters speak directly into the lens during conversations, breaking the fourth wall and making us unwilling participants in their psychological games. It’s a technique that shouldn’t work, that should pull us out of the story, but instead draws us deeper into its web. The framing consistently places Clarice as an outsider – she’s often shot from slightly above, making her appear smaller in rooms full of men, reinforcing her vulnerability while simultaneously highlighting her determination.

There’s a scene that haunts me particularly – when Clarice discovers the head in the storage unit. The way the camera follows her through that maze of identical garage doors creates a mounting sense of dread that pays off not with a jump scare, but with the quiet horror of realization. This is Demme at his finest, understanding that true fear lives in anticipation, in the moment just before revelation.

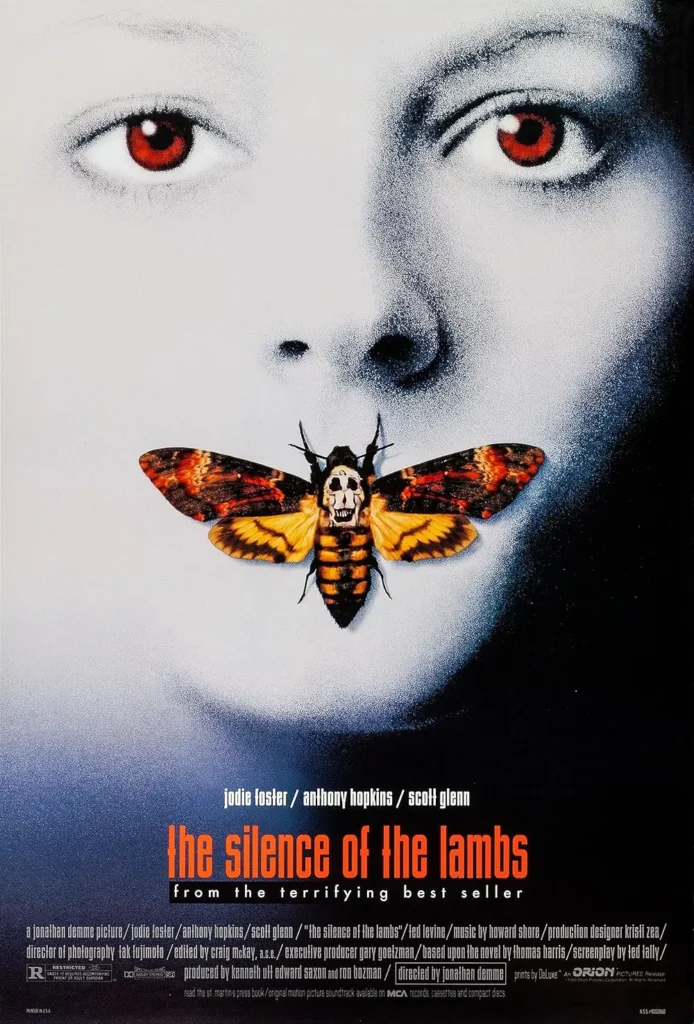

The film’s exploration of transformation deserves special mention. Buffalo Bill’s grotesque metamorphosis serves as a dark mirror to Clarice’s own evolution from trainee to agent. Both are trying to shed their old selves, to become something new. But while Bill’s transformation is an act of violence against others, Clarice’s is an internal battle, a fight to overcome her own trauma without losing her humanity in the process. The death’s head moths, with their eerie skull markings, become perfect symbols of this duality – beauty and death intertwined.

The Silence of the Lambs impact on cinema cannot be overstated. It shattered the ceiling for what horror could be, winning Academy Awards and forcing critics to recognize that terror could come wrapped in artistic excellence. Before Silence, horror was largely relegated to the shadows of “genre films.” After, the doors were thrown open for sophisticated psychological thrillers that didn’t shy away from darkness. Every smart horror film that followed – from Seven to Get Out – owes a debt to the trail this film blazed.

What makes The Silence of the Lambs a true masterpiece is how it weds technical brilliance to profound psychological insight. It’s a film that understands the relationship between hunter and hunted is never simple, that power dynamics can shift in the space of a single conversation, that the greatest monsters are those who understand us too well.

When I first saw The Silence Of The Lambs, I was struck dumb by its power. Decades later, it still has the ability to reach into my chest and squeeze. In the end, we’re all left like Clarice – changed by our dance with darkness, unable to unhear the screams, unable to unsee the monsters wearing human faces, and perhaps most disturbingly, unable to forget how close we came to understanding them.