Key Facts

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Release Date | October 1, 1974 (Austin premiere); October 11, 1974 (wide release) |

| Runtime | 83 minutes |

| Director | Tobe Hooper |

| Writers | Tobe Hooper, Kim Henkel |

| Cinematographer | Daniel Pearl |

| Editors | Sallye Richardson, Larry Carroll |

| Music/Sound Design | Tobe Hooper, Wayne Bell |

| Camera Format | 16mm reversal stock (blown up to 35mm) |

| Budget | $80,000 to $140,000 |

| Box Office | $26.7 to $30.8 million worldwide |

| MPAA Rating | Initially X, cut to R |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.85:1 (35mm blow-up from 1.33:1) |

| Distribution | Bryanston Distributing Company |

Introduction & Overview

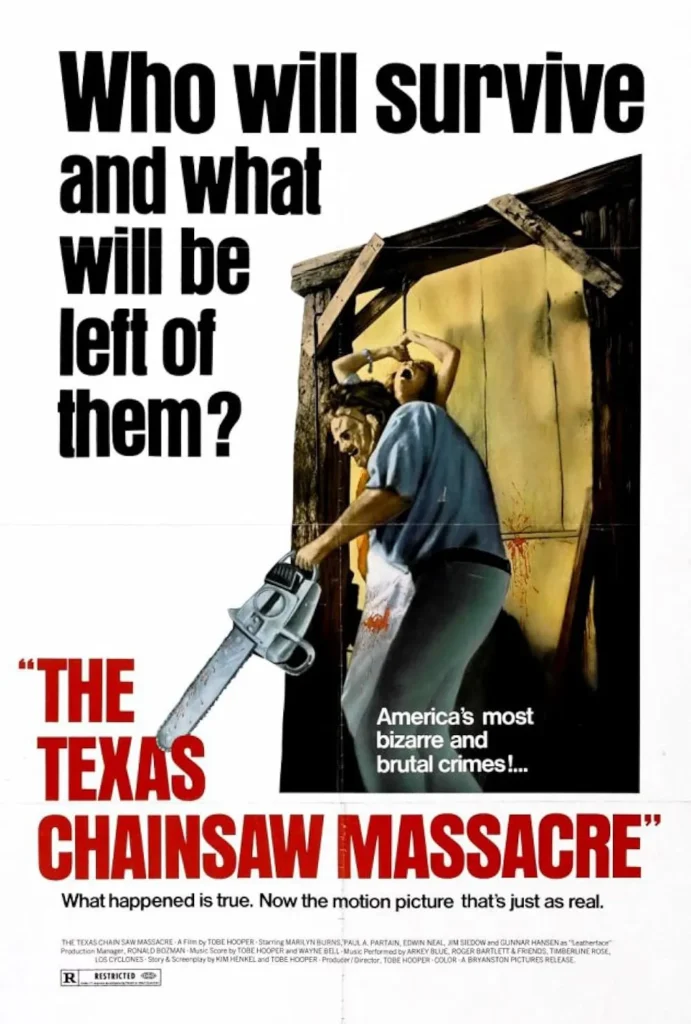

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre erupted into American theaters in 1974 like a molotov cocktail thrown at the horror establishment. Shot on grainy 16mm film stock in the punishing Texas heat, Tobe Hooper’s breakthrough feature abandoned Gothic castles and midnight shadows for something far more disturbing: brutality in broad daylight, captured with the unflinching eye of a documentary camera.

The film’s power stems from its radical aesthetic choices. Where traditional horror relied on darkness and suggestion, Hooper dragged his audience into a sun-bleached inferno where violence felt immediate and inescapable. Daniel Pearl’s cinematography rendered rural Texas as an alien wasteland of washed-out yellows and oppressive heat shimmer, while the soundscape of industrial noise and non-musical atonality created a sensory assault unlike anything audiences had experienced.

The infamous “based on a true story” claim that opens the film was pure fabrication, yet it became integral to the movie’s mythology. While drawing loose inspiration from Wisconsin killer Ed Gein (who also influenced Psycho and The Silence of the Lambs), the events depicted were entirely fictional. This calculated lie, delivered via John Larroquette’s somber narration, transformed a low-budget shocker into something that felt ripped from newspaper headlines.

Why The Texas Chain Saw Massacre Matters

Understanding Chain Saw’s significance requires recognizing how completely it revolutionized American horror cinema. Before 1974, horror movies followed established Gothic conventions: shadowy castles, clearly defined monsters, and supernatural threats that could be dismissed upon leaving the theater. Hooper shattered those conventions by creating something that felt documentary-real, disturbingly plausible, and deeply rooted in contemporary American anxieties.

Historical Impact on Independent Film Chain Saw proved that micro-budget filmmakers could compete with major studios by abandoning their rules entirely. Its $140,000 investment returned over $26 million worldwide, inspiring countless indie horror filmmakers and establishing the template for profitable genre filmmaking. The production’s guerrilla techniques (shooting without permits, using non-professional actors, embracing documentary-style camerawork) became standard practice for independent cinema.

Cultural Anxieties Made Manifest The film weaponized multiple fears plaguing 1970s America: post-Vietnam disillusionment, Watergate-era distrust, economic recession, and the oil crisis. By depicting a collapsed rural economy where former slaughterhouse workers had turned to cannibalism, Hooper created a horror that felt immediate and relevant. Unlike Gothic monsters that represented abstract evil, the Sawyer family embodied specific American failures: industrial collapse, family breakdown, and the dark side of self-reliance.

Influence on Modern Horror From suburban slasher grammar in Halloween to found-footage realism in Blair Witch, Chain Saw’s fingerprints are everywhere. It established the “final girl” archetype, pioneered the daylight horror aesthetic, and demonstrated that suggestion could be more powerful than graphic violence. The film’s DNA appears in everything from Halloween‘s suburban menace to The Blair Witch Project‘s found-footage realism, from Hostel‘s torture chambers to Hereditary‘s family dysfunction.

Aesthetic Revolution Chain Saw’s sun-bleached, documentary-style cinematography rejected horror’s reliance on darkness and shadows. This choice made violence feel inescapable: there was nowhere to hide in the harsh Texas light. The technique influenced not just horror but American cinema broadly, contributing to the New Hollywood movement’s embrace of naturalistic filmmaking.

Reception & Critical Response

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre’s critical journey mirrors its transformation from exploitation curiosity to recognized masterpiece. Initial reviews revealed the deep divide between mainstream critics and horror enthusiasts, while later academic reassessment elevated the film to art-house respectability.

Initial Critical Reception Roger Ebert, typically dismissive of horror films, was surprisingly measured, writing: “It’s a film I’ll never watch again, but I admire it as a work of art.” He recognized Hooper’s technical achievement while acknowledging his personal revulsion. Variety was less generous, calling it “a degrading presentation” that “amounts to a geek show,” though they conceded its “undeniable impact.” The Village Voice‘s Tom Allen proved more prescient, praising its “hallucinatory intensity” and predicting its influence on American cinema.

Festival Reactions The film’s 1974 festival run generated controversy and walkouts but also serious critical attention. At the London Film Festival, audience members fled the screening while critics debated its artistic merit. The Cannes market screening (unofficial) became legendary for its shocked audience response. These reactions, rather than damaging the film’s reputation, enhanced its mystique and suggested deeper artistic qualities beneath the surface exploitation.

Academic Reassessment By the 1980s, film scholars began serious analysis of Hooper’s achievement. Robin Wood’s influential essay identified the film as a “masterpiece” that used horror conventions to critique American capitalism. Critics praised its environmental themes, feminist subtexts (through Sally’s survival), and innovative sound design. The Museum of Modern Art’s 1979 screening legitimized the film in academic circles, followed by retrospectives at the Pacific Film Archive and American Cinematheque.

Modern Critical Consensus Today’s critics recognize Chain Saw as a pivotal work of American cinema. It appears on numerous “greatest horror films” lists and earned inclusion in the National Film Registry. Critics now praise elements they once dismissed: the stark photography, minimalist score, and powerhouse performances. The film’s reputation evolved from “trash” to “art,” proving that genre cinema could achieve genuine artistic significance.

Release, Censorship, Restorations

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre’s path to audiences was as brutal as its content. Originally submitted to the MPAA with hopes for a PG rating (Hooper naively believed the lack of explicit gore would earn leniency), the MPAA pushed for severe cuts citing “intense and sustained terror.” After trims it was released with an R rating, though many theaters ran unrated prints to preserve Hooper’s vision.

International censorship proved even more severe. The British Board of Film Classification banned the film outright for 25 years, making it a centerpiece of the “video nasty” moral panic. When finally released uncut in 1999, UK audiences discovered a film far less graphic than its reputation suggested. Australia refused classification until 1984, while the movie faced bans or heavy cuts in France, Germany, Sweden, Norway, Brazil, Singapore, and Chile. Each prohibition only enhanced its outlaw mystique.

The film’s preservation journey reflects its evolution from grindhouse fodder to recognized art. The 2005 2K restoration from original 16mm A/B rolls corrected decades of color fading while preserving the intentionally rough texture. Hooper supervised a definitive 4K restoration in 2014, premiered at Cannes Directors’ Fortnight, which balanced authenticity with clarity by maintaining the grainy, documentary feel while revealing previously obscured details in the shadows and sun-bleached exteriors.

For the 50th anniversary in 2024, boutique labels like Arrow Video released new 4K UHD editions featuring both the original mono track and restored surround mixes. The film entered the Library of Congress’s National Film Registry, with archival elements preserved at the Academy Film Archive and Museum of Modern Art.

Filming Locations

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre’s locations have become pilgrimage sites for horror fans, though many have been dramatically transformed since 1973. The production shot across Central Texas, primarily in Round Rock, Leander, and Bastrop: areas chosen for their isolation and decay.

The Sawyer House The film’s most iconic location (the Victorian farmhouse where the cannibal family lives) originally stood in Round Rock, Texas. Built in the 1900s, the deteriorating structure perfectly embodied rural decay. After filming, the house changed hands multiple times before being purchased by fans who relocated it to Kingsland, Texas, where it operated for years as “Grand Central Café,” a restaurant housed within the actual filming location. The relocation preserved the structure while allowing fans to visit and dine where Sally endured her terrifying ordeal.

Gas Station and General Store The Billings Store on TX-304 near Bastrop, where Sally’s group first encounters the hitchhiker and later where Sally seeks help, still operates as “The Gas Station.” This horror-themed establishment now offers barbecue and cabins, maintaining many original details from the filming while embracing its cinematic history. The proprietors celebrate the horror legacy while serving genuine Texas barbecue.

Cemetery Scenes The opening graveyard sequence was filmed at Bagdad Cemetery in Leander, still accessible to respectful visitors. The deteriorating headstones and Spanish moss create an appropriately gothic atmosphere. The famous body arrangement atop the tombstone (Sally’s grandfather’s desecrated grave) was constructed specifically for filming using props rather than actual remains.

Other Notable Locations The railroad tracks where the group’s van gets stuck were shot near Bastrop State Park. The quarry swimming hole scenes utilized a natural limestone quarry popular with locals. Most surrounding farmland has been developed, but dedicated fans can still identify many background locations using production stills as reference.

Plot Summary

Five young adults venture into rural Texas to investigate reports of vandalized graves, setting in motion a descent into primal horror that would redefine American cinema.

The group consists of Sally Hardesty and her wheelchair-bound brother Franklin, along with friends Jerry, Kirk, and Pam. They travel through sun-scorched countryside to check on Sally’s grandfather’s grave after radio reports of cemetery vandalism. Their first warning comes via a disturbing hitchhiker they pick up, who demonstrates his family’s slaughterhouse skills with alarming enthusiasm before cutting Franklin’s arm and burning his hand with their photographs. When thrown from the van, he smears a bloody handprint on the vehicle, marking them for what’s to come.

Running low on gas at an apparently abandoned station, the group splits up to explore the area. Kirk and Pam discover a seemingly abandoned farmhouse, hoping to trade gasoline for antiques. Kirk’s investigation leads him to encounter Leatherface, who kills him with a sledgehammer and drags his body inside. When Pam follows, she stumbles into a house decorated with bones, feathers, and furniture made from human remains before being hung on a meat hook (alive but helpless).

Jerry searches for the missing couple, finding Pam barely alive in a freezer before meeting his own violent end. As darkness falls, Sally and Franklin investigate, only for Leatherface to emerge with his chainsaw, killing Franklin and sending Sally fleeing through the night.

Sally’s escape leads her back to the gas station, where the proprietor reveals himself as part of the cannibal family. Bound and gagged, she’s brought to their house for a grotesque dinner with Leatherface, the hitchhiker, the Cook, and ancient Grandpa. After enduring psychological torture and a failed attempt to have the decrepit Grandpa kill her with a hammer, Sally breaks free at dawn. The hitchhiker is killed by a passing truck, and Sally escapes in another vehicle’s bed, laughing maniacally as Leatherface performs his frustrated chainsaw dance in the morning sun: an image of pure, impotent rage that became one of cinema’s most iconic endings.

Cast & Characters

Sally Hardesty (Marilyn Burns): Prototype Final Girl Endurance

Marilyn Burns created the template for horror’s “final girl” through sheer physical and emotional commitment. Her Sally transforms from carefree road-tripper to primal survivor across the film’s punishing runtime. Burns performed her own stunts, running barefoot through actual briars, enduring real cuts and bruises. Her prolonged screaming during the dinner scene (which famously required 26 straight hours of shooting in stifling heat) remains viscerally affecting. Critics still cite her bloodied, hysterical laughter during the escape as one of horror cinema’s greatest moments of cathartic terror. Burns’ willingness to endure genuine discomfort created a performance that transcends acting: it feels like documented trauma.

Leatherface (Gunnar Hansen): Masks, Tool Choice, Nonverbal Terror

Gunnar Hansen’s Leatherface revolutionized movie monsters by combining hulking physicality with childlike vulnerability. Hansen researched his role by visiting institutions for developmentally disabled individuals, creating a character who kills not from malice but from fear and confusion. The leather mask (supposedly human skin) functions as both disguise and identity, with different “faces” for different moods. His weapon choice reflected practical concerns (chainsaws were common rural tools) and symbolic ones (mechanized violence, industrial death). Unlike the calculated killers who followed, Leatherface operates on instinct, making him unpredictable and genuinely frightening. Hansen wore the same blood-soaked outfit for the entire shoot; it was never washed, building up authentic grime and stench.

The Family: The Cook, The Hitchhiker, Grandpa. Dysfunctional Domesticity

The cannibal clan represents a diseased parody of American family values. Jim Siedow’s Cook oscillates between stern patriarch and sadistic torturer, complaining about his brothers’ methods while orchestrating horrors. Edwin Neal’s Hitchhiker embodies unstable menace, giggling maniacally while demonstrating his slaughterhouse skills and photographing victims. John Dugan’s Grandpa, supposedly 137 years old, appears nearly corpse-like yet represents the family’s twisted legacy. Together, they create a unit bound by shared madness and economic necessity: former slaughterhouse workers who’ve turned to cannibalism as their industry collapsed.

Behind the Scenes

Story Origins: Post-Vietnam Malaise, Meat Industry Imagery, Ed Gein Echoes

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre emerged from multiple cultural anxieties plaguing 1970s America. Hooper and co-writer Kim Henkel drew inspiration from post-Vietnam disillusionment, creating a film that reflected national trauma through rural horror. The meat industry imagery wasn’t accidental; Hooper’s father worked in meat processing, providing intimate knowledge of slaughterhouse practices that informed the film’s visceral details.

While marketing claimed “true story” origins, the actual inspiration came from Wisconsin killer Ed Gein, whose crimes involving grave robbing and human skin crafts had already influenced Psycho and Deranged. Hooper transformed Gein’s isolated pathology into a family enterprise, suggesting that such horrors weren’t aberrations but logical extensions of American industry and family structures.

The project originated when Hooper, frustrated by the difficulty of securing funding for personal films, decided to make something undeniably commercial. “I wanted to make a film that would be so violent and disturbing it would make people think twice about violence,” he later explained, though the irony of using exploitation techniques to critique exploitation wasn’t lost on him.

Production Conditions: Heat, Stench, Long Takes, Near-Verité Approach

Filming during Texas’s brutal summer of 1973 created conditions that enhanced the movie’s hellish atmosphere. Temperatures regularly exceeded 100°F, while the house’s interior (decorated with real animal bones and rotting meat) reeked unbearably. These weren’t artistic choices but budget necessities that accidentally improved the film’s authenticity.

Burns’ injuries were largely real: running through briars, cutting herself on props, enduring genuine exhaustion during the extended dinner sequence. The dinner scene’s marathon 26-hour shoot (caused by technical difficulties and Hansen’s claustrophobia-inducing mask) pushed everyone to their physical limits.

Hooper’s near-verité approach emphasized long takes and minimal coverage, partly from film stock limitations but mostly from aesthetic choice. The famous tracking shot following Sally’s escape (handheld camera pursuing her through the woods) was achieved through dangerous night shooting without permits or safety precautions. This guerrilla approach created documentary-style immediacy that separated Chain Saw from polished studio horror.

Cinematography: Sun-Bleached Palette, Macro Shots, Flash-Bulb Sound Motif

Daniel Pearl’s cinematography revolutionized horror aesthetics by rejecting darkness for harsh, inescapable daylight. Using 16mm Eastman Ektachrome stock, Pearl created a sun-bleached palette that made violence feel documentary-real. The overexposed, high-contrast look wasn’t just stylistic; it reflected the production’s low budget and Pearl’s inexperience, yet these limitations produced innovative results.

Pearl’s macro photography of decomposing animals and insects opened the film, establishing themes of death and decay while creating an unsettling tone. The famous armadillo shot (actually roadkill Pearl discovered) exemplified the production’s resourcefulness in finding horror in everyday reality.

The recurring flash-bulb sound motif, triggered by the hitchhiker’s Polaroid camera, became an audio signature that punctuated violent moments. This sound design element, created by Hooper and Wayne Bell, demonstrated how simple techniques could achieve maximum psychological impact.

Art Direction and Props: Bones, Feathers, Furniture of Flesh

The film’s grotesque art direction emerged from necessity and inspiration. Unable to afford elaborate sets, production designer Bob Burns (working with minimal budget) scavenged materials from local slaughterhouses and farms. The bone furniture and feather decorations were assembled from genuine animal remains, creating authentic decay and stench that affected cast and crew.

The famous “furniture of human bones” was actually constructed from cattle bones obtained from meat processing facilities. Burns arranged these elements to suggest human origin without actually using human remains: a technique that satisfied both budget constraints and legal requirements. The hanging feathers and wind chimes created from bones weren’t just decorative; they produced unsettling sounds that enhanced the audio landscape.

Leatherface’s masks were crafted from real leather, designed to suggest human skin without crossing legal boundaries. Each mask supposedly reflected different moods: the “killing mask,” the “old lady mask” for domestic duties, and the “pretty woman mask” for special occasions. This attention to detail demonstrated the production’s commitment to creating authentic horror within exploitation constraints.

Soundscape and Minimal Score: Industrial Noise, Atonality

The film’s revolutionary sound design abandoned traditional horror scoring for industrial noise and atonal compositions. Hooper and Wayne Bell created a soundscape that felt more like audio verité than movie music, using everyday sounds (metal scraping, machinery grinding, animal noises) to build tension.

The minimal score emphasized percussion and dissonance, avoiding melodic elements that might provide emotional comfort. When music appeared, it was often created from everyday objects (metal sheets, industrial tools, and found instruments), maintaining the film’s naturalistic aesthetic while creating genuine unease.

The famous chainsaw motor sound became a character itself, with Bell recording multiple chainsaw models to find the most unsettling frequency. The decision to feature the chainsaw’s audio more prominently than its visual appearance demonstrated the power of sound to create horror through suggestion rather than graphic display.

Themes & Analysis

American Consumerism and the Slaughterhouse Metaphor

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre functions as a savage critique of American consumerism, using the slaughterhouse as both literal setting and symbolic framework. The Sawyer family represents the dark endpoint of capitalist logic: when their legitimate slaughtering business collapsed due to industrial modernization, they simply found new livestock (human beings). This isn’t random madness but logical adaptation to economic pressures.

The film’s meat industry imagery isn’t coincidental but central to its meaning. Hooper presents humans as cattle, processed through the same mechanisms that transform animals into commodities. Pam’s meat hook suspension mirrors standard slaughterhouse practice, while the bone furniture suggests complete utilization of “product”: nothing wasted, everything consumed. The Cook’s pride in their killing methods reflects industrial efficiency applied to human processing.

Sally’s prolonged torment during the dinner scene represents the consumer’s relationship to hidden violence. Just as most Americans consume meat without witnessing slaughter, they participate in systems of violence while maintaining comfortable distance. The film forces viewers to confront the brutality underlying their consumption patterns, making explicit the violence typically hidden by industrial processes.

Family Breakdown

The Sawyer clan presents family structure as a source of horror rather than comfort. Their dysfunctional domesticity (complete with assigned roles, shared traditions, and generational continuity) mirrors normal family dynamics while revealing their potential for evil. Grandpa represents patriarchal authority taken to its extreme logical conclusion, a barely living figurehead whose “wisdom” consists of murder techniques.

The Cook functions as disciplinarian and provider, frustrated by his brothers’ sloppiness while orchestrating their crimes. The Hitchhiker embodies rebellious youth channeled into sadism. Leatherface, the developmentally disabled member, follows family expectations without understanding their moral implications. Together, they create a unit that’s simultaneously recognizably American and utterly alien.

This family structure critiques American idealization of family values by showing how family loyalty can enable atrocity. The Sawyers protect each other, share resources, and maintain traditions (all supposedly positive family traits that become horrifying in this context). Their unity makes them more dangerous than individual killers, suggesting that social bonds can facilitate rather than prevent evil.

Rural vs Urban Fear

Chain Saw exploits urban audiences’ fears of rural America while simultaneously critiquing urban prejudices. The film’s young protagonists represent urban/suburban middle-class values (education, mobility, consumer choices) venturing into a rural landscape they neither understand nor respect. Their assumptions about rural backwardness prove fatally naive when confronted with genuine danger.

Yet the film doesn’t simply validate urban fears; it suggests that rural dysfunction stems from urban-driven economic changes. The slaughterhouse closure represents industrial modernization that benefits urban consumers while devastating rural communities. The Sawyers’ cannibalism reflects this economic abandonment: forced to become predators when their legitimate livelihood disappeared.

This dynamic creates complex horror that works on multiple levels. Urban audiences fear rural otherness while rural audiences recognize economic abandonment. The film suggests that urban-rural divisions create mutual incomprehension that benefits neither side, with violence emerging from this cultural gap.

Violence Mostly Implied, Not Shown

The film’s reputation for graphic violence far exceeds its actual gore content: a testament to Hooper’s masterful use of suggestion over explicit display. Most violence occurs off-screen or through reaction shots, allowing viewers’ imaginations to create personalized horror more disturbing than any special effect could achieve.

The famous meat hook scene shows no penetration, only Pam’s agonized response and the hook’s positioning. Kirk’s sledgehammer death happens largely through sound and aftermath rather than graphic depiction. Even the chainsaw (the film’s signature weapon) never visibly cuts human flesh, maintaining its power through audio and implication rather than visual confirmation.

This restraint wasn’t just artistic choice but practical necessity: the low budget couldn’t afford elaborate gore effects. Yet this limitation produced superior results, proving that horror’s power lies in psychological impact rather than graphic display. The film’s enduring ability to disturb viewers decades later demonstrates the superiority of suggestion over explicit violence in creating lasting fear.

Cultural Impact & Legacy

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre’s influence extends far beyond horror cinema, reshaping American independent film and establishing templates still followed today. Its $140,000 budget returning over $26 million worldwide proved that micro-budget filmmakers could compete with major studios by abandoning conventional approaches entirely.

Independent Film Precedent Chain Saw legitimized guerrilla filmmaking techniques that became standard practice for independent cinema. Shooting without permits, using non-professional actors, embracing documentary-style camerawork, and turning budget limitations into aesthetic choices (all pioneered by Hooper’s production) became the foundation for American independent film. Directors from John Carpenter to Kevin Smith to The Blair Witch Project creators followed the template Chain Saw established.

Controversy and Cultural Dialogue The film sparked nationwide debates about violence in media, artistic freedom, and censorship that continue today. Its banning in multiple countries and “video nasty” classification created international controversy that enhanced its cultural significance beyond entertainment. Academic critics began serious analysis of horror cinema partly in response to Chain Saw’s obvious artistic ambitions disguised as exploitation material.

Critical Reappraisal The film’s journey from drive-in exploitation to museum screenings illustrates changing attitudes toward genre cinema. Robin Wood’s influential critical reassessment identified Chain Saw as a “masterpiece” of American cinema, leading to retrospectives at major institutions including the Museum of Modern Art, Pacific Film Archive, and American Cinematheque. Its inclusion in the National Film Registry confirmed its transformation from “trash” to “art.”

Museum Screenings and Academic Recognition Major art institutions now regularly screen Chain Saw as part of American cinema retrospectives. University film programs analyze its techniques, themes, and influence. This academic acceptance validated genre cinema’s potential for serious artistic achievement, opening doors for later horror films to receive critical respect without abandoning their genre roots.

Franchise & Influence: Quick-Reference Chronological Guide

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre spawned a complex franchise with multiple timelines, reboots, and rights transfers. Here’s a chronological guide to navigate the messy continuity:

Original Timeline

- The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974): Tobe Hooper’s original masterpiece

- The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (1986): Hooper’s satirical sequel, 13 years later

- Leatherface: The Texas Chainsaw Massacre III (1990): New Line Cinema’s unsuccessful reboot attempt

- Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Next Generation (1994): Kim Henkel’s bizarre continuation featuring early appearances by Renée Zellweger and Matthew McConaughey

Platinum Dunes Reboot Series

- The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (2003): Marcus Nispel’s mainstream horror reboot

- The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning (2006): Prequel to the 2003 remake

Netflix/Legendary Series

- Texas Chainsaw Massacre (2022): Netflix direct sequel to 1974 original, ignoring all other entries

Upcoming Releases

- Texas Chainsaw Massacre (TBA): Another reboot currently in development

Leatherface as Archetype Gunnar Hansen’s Leatherface established the template for masked slashers that dominated 1980s horror. Unlike Psycho’s Norman Bates, who hid his pathology behind normalcy, Leatherface wore his dysfunction literally: masks made from victims’ skin that reflected different psychological states. His childlike mentality combined with immense physical power created a monster both pitiable and terrifying.

Michael Myers (Halloween) [Link to Halloween (1978) Guide], Jason Voorhees (Friday the 13th), and countless imitators followed Leatherface’s template: masked killers with signature weapons, minimal dialogue, and apparent invulnerability. However, most successors abandoned Leatherface’s psychological complexity for simpler supernatural evil, losing the original’s disturbing humanity.

Influence on Modern Horror Subgenres Torture Cinema: Films like Saw, Hostel, and The Devil’s Rejects drew directly from Chain Saw’s captivity sequences and industrial death imagery, though they emphasized explicit violence over psychological terror.

Found Footage Realism: The Blair Witch Project, [REC], and Paranormal Activity adopted Chain Saw’s documentary-style camerawork and naturalistic performances to create visceral authenticity.

Indie Horror Renaissance: Contemporary filmmakers from Ari Aster (Hereditary) to Robert Eggers (The Witch) follow Chain Saw’s model of combining artistic ambition with genre thrills, proving horror can achieve critical respect without abandoning its fundamental purpose.

Rural Horror Revival: Films like The Hills Have Eyes, Wrong Turn, and Midsommar continue Chain Saw’s exploration of urban-rural cultural conflicts, using isolated settings to examine contemporary American anxieties.

Technical Innovations Chain Saw’s 16mm-to-35mm blow-up process influenced countless low-budget productions. Its sound design techniques (minimal scoring, industrial noise, extended silence) became standard for naturalistic horror. The film’s day-lit horror aesthetic challenged genre conventions and expanded horror’s visual vocabulary beyond Gothic shadows and supernatural darkness.

Viewing Guide

Which Cut to Watch Any restoration from 2014 onward preserves Hooper’s original vision; the film was never significantly altered for different markets after its initial MPAA negotiations. The definitive 4K restoration, supervised by Hooper himself, balances authenticity with clarity while maintaining the intentionally rough texture that’s integral to the film’s impact.

Avoid bootlegs or transfers predating 2005, as these compromise the carefully crafted sun-bleached color palette that’s crucial to the film’s aesthetic. The original mono soundtrack offers the most authentic experience, though Hooper-approved surround remixes are acceptable for home viewing.

Audio Considerations The film’s revolutionary sound design demands quality audio reproduction. Hooper and Wayne Bell’s industrial soundscape relies on subtle audio details (metal scraping, machinery grinding, environmental sounds) that disappear in compressed formats. The famous chainsaw motor frequencies require full-range speakers to achieve their unsettling psychological effect.

Recommended Double Features

- Night of the Living Dead (1968) [Link to Night of the Living Dead Guide]: Romero’s zombie classic shares Chain Saw’s documentary realism and social commentary

- The Hills Have Eyes (1977): Wes Craven’s desert horror follows Chain Saw’s urban-meets-rural template

- Deranged (1974) [Link to Deranged Guide]: Roberts Blossom’s Ed Gein adaptation, released the same year, offers interesting comparison

- Last House on the Left (1972): Craven’s earlier brutality study shares Chain Saw’s unflinching approach to violence

Optimal Viewing Conditions Chain Saw benefits from theatrical presentation; the communal experience of shared terror enhances its psychological impact. If watching at home, dim lighting preserves the film’s careful contrast balance while allowing the sun-bleached daytime sequences to maintain their oppressive intensity. Avoid watching alone on first viewing; the film’s psychological effects can be genuinely disturbing without social context to process the experience.

FAQs

Is The Texas Chain Saw Massacre based on a true story? No, despite the opening claim. While loosely inspired by Wisconsin killer Ed Gein’s crimes (grave robbing, crafting items from human remains), the specific events are entirely fictional. The “true story” assertion was a marketing decision designed to enhance the film’s psychological impact. Gein’s crimes also inspired Psycho, The Silence of the Lambs, and Deranged, but none depicted actual events. Hooper and co-writer Kim Henkel created original characters and situations, using Gein’s case as one of several inspirations rather than direct adaptation.

What chainsaw model was used in filming? Production used the Poulan 306A (the distinctive green model popular in 1970s Texas). The chainsaw’s motor sound that became the film’s audio signature was carefully recorded by sound designer Wayne Bell, who tested various models to find the most psychologically unsettling frequency. For safety during close-up filming, the chain was often removed; the weapon’s power came from audio and implication rather than actual cutting capability.

Where can I visit the filming locations? The iconic Sawyer house was relocated from Round Rock to Kingsland, Texas, where it operated for years as “Grand Central Café” housed within the actual filming location. The gas station from the film operates as “The Gas Station” on TX-304 near Bastrop, offering horror-themed barbecue and cabins. Bagdad Cemetery in Leander, where the opening graveyard scenes were shot, remains accessible to respectful visitors. Most other locations have been developed, though dedicated fans can identify background spots using production stills.

Is Leatherface based on Ed Gein? Partially. Wisconsin killer Ed Gein’s crimes (grave robbing, crafting furniture and clothing from human remains) inspired multiple horror characters including Leatherface, Norman Bates (Psycho), and Buffalo Bill (The Silence of the Lambs). However, Hooper transformed Gein’s isolated pathology into a family enterprise, making Leatherface more childlike and sympathetic than the real killer. The character combines Gein’s skin-crafting with original elements like the chainsaw weapon and family dynamics.

Why is it called “Chain Saw” instead of “Chainsaw”? The original 1974 title uses two words: “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.” This reflects the period’s common spelling for the tool, though “chainsaw” (one word) became standard later. The sequels and remakes have used both spellings inconsistently. The two-word version also creates a more deliberate, ominous rhythm that emphasizes each component of the weapon’s identity.

How gory is the film really? Far less graphic than its reputation suggests. Hooper masterfully uses suggestion, sound design, and reaction shots to imply violence without showing it. The meat hook scene shows no penetration, the chainsaw never visibly cuts flesh, and most violence occurs off-screen. This restraint makes the film more psychologically disturbing than graphic horror; your imagination creates personalized terror more effective than any special effect. The film’s reputation for extreme gore demonstrates the power of suggestion over explicit display.

Why do people remember it as being so much more violent than it actually is? The film’s genius lies in psychological manipulation rather than graphic content. Hooper’s use of industrial sounds, claustrophobic camerawork, sustained tension, and visceral reactions creates an impression of extreme violence that exceeds what’s actually shown. The dinner sequence’s psychological torture, combined with Marilyn Burns’ genuinely distressed performance, creates trauma that viewers remember as physical rather than mental. This demonstrates filmmaking’s power to create subjective reality that surpasses objective content; the most effective horror happens in your mind, not on screen.