For over a century, vampire horror movies have captivated audiences with their unique blend of terror, seduction, and supernatural power. Unlike other movie monsters that inspire pure fear, vampires occupy a fascinating gray area. They exist between horror and desire. Between repulsion and attraction.

From the grotesque Count Orlok of 1922’s Nosferatu to the sparkling Edward Cullen of the Twilight saga, vampire cinema has continuously evolved. Each generation gets the vampires it deserves—and fears.

What makes vampire horror movies so enduringly popular? The answer lies in their remarkable adaptability as metaphors. Vampires have served as symbols for disease and contagion, forbidden sexuality, foreign invasion, class warfare, and the eternal human struggle between civilization and primal desire. They embody our deepest fears about mortality while simultaneously offering the tantalizing promise of immortality and power.

This comprehensive guide traces the evolution of vampire cinema from its folkloric origins through the silent era’s visual innovations, the golden age of Universal horror, Hammer Films’ Technicolor renaissance, and into the modern era of sympathetic vampires, action heroes, and romantic anti-heroes. We’ll explore how vampire movies have consistently pushed boundaries—whether technical, artistic, or social—while maintaining their grip on popular culture.

Whether you’re a horror aficionado seeking to understand the genre’s rich history or a casual fan curious about why vampires remain cinema’s most adaptable monsters, this exploration reveals how vampire horror movies continue to sink their teeth into our collective imagination. They refuse to stay buried in cinema’s past.

History of Vampire Horror Movies: From Folklore to Film

Folklore Foundations: The Real Origins of Vampire Legends

The vampire’s journey to cinema began not in the “Dark Ages” of Medieval Europe, as commonly believed, but in the more recent localized traditions of Eastern Europe. The story starts around a thousand years ago in Bulgaria. These weren’t the sophisticated bloodsuckers we know today.

The earliest vampire-like creatures emerged as “ghost monsters”—non-corporeal entities that shared more characteristics with poltergeists than aristocratic predators. These original Slavic vampires were blamed for spreading disease throughout villages. They served as scapegoats for unexplainable illnesses in an era before understanding of bacteria and viruses.

The etymology of “vampire” remains hotly debated among scholars. The word likely derives from the Old Slavic term “upir” or “vampir.” Some translations suggest “the thing at the feast or sacrifice”—hinting at a dangerous spiritual entity believed to manifest at rituals for the dead. This term was likely a euphemism. People avoided uttering the creature’s true name. Fear just ran that deep.

These spectral beings didn’t propagate through bites or consume blood. They were simply malevolent forces causing widespread havoc. The transformation of vampires from incorporeal spirits to corporeal blood-drinkers occurred during the 18th century’s “Great Vampire Epidemic” (1725-1755). Vampire myths literally “went viral” across Europe.

Key Takeaways: Vampire Folklore Origins

- Original vampires were non-corporeal “ghost monsters” from Eastern Europe

- Blood-drinking was added in the 18th century to make vampires more “scientific”

- Real diseases like rabies and pellagra influenced vampire characteristics

- The Great Vampire Epidemic spread vampire beliefs across Europe

This period coincided with widespread disease outbreaks, political instability, and cultural suppression in Eastern Europe. Real diseases exhibited symptoms strikingly resembling vampire folklore. Rabies caused biting transmission, foaming at the mouth, light sensitivity, and aggressive behavior. Pellagra created corpse-like skin conditions. The medical ignorance of the time fueled their supernatural explanations.

The addition of blood consumption to vampire lore represented a deliberate conceptual evolution. It made vampires “more believable, more corporeal than incorporeal, more scientific than supernatural” to 18th-century Western intellectuals. Blood was widely believed to possess medicinal qualities. The practice of “medicinal cannibalism” was common across all social levels. This scientific veneer allowed vampires to maintain credibility as sources of fear even as rational thought gained prominence.

Literary Precursors: Building the Foundation

Before Bram Stoker created the definitive vampire archetype, several key literary works established the foundation for cinematic vampires. Robert Southey’s Thalaba the Destroyer (1801) contained the first mention of vampires in English literature. The vampiric element remained marginal to the overall narrative. But the seed was planted.

John William Polidori’s The Vampyre (1819) marked a pivotal transformation. It originated during the same literary contest that produced Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Talk about a productive summer. Polidori introduced Lord Ruthven, an “aristocratic rake” who represented a profound shift from grotesque peasant revenants to sophisticated, affluent predators.

This transformation was crucial. It moved the horror from literal decay and contagion to moral corruption and seductive power operating within polite society. The monster could now walk among the elite. It could charm its way into drawing rooms and bedchambers.

J. Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla (1871-72) predated Dracula by 26 years and established the “prototypical lesbian vampire.” The novella explored forbidden same-sex desires within Victorian society’s repressive framework. Carmilla’s queerness intertwined with her monstrosity. She represented everything Victorian society feared about female sexuality and independence.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) synthesized existing folklore and earlier vampire fiction into the definitive archetype. Count Dracula possessed formidable supernatural abilities—superhuman strength, shape-shifting, hypnotic powers, and the ability to transform others through his bite. Stoker invented several lasting vampire characteristics. The inability to enter homes uninvited. The need to sleep on homeland soil. These rules became gospel for future vampire creators.

Interestingly, sunlight merely weakened Dracula rather than proving fatal in Stoker’s novel. That innovation would come from cinema itself.

Vampire Horror in the Silent Era: Creating Visual Language

Early Experiments and Cinema’s First Vampires

Cinema’s earliest encounters with vampire subjects were tentative and often misunderstood. George Méliès’ The Devil’s Castle (1896), sometimes cited as the first vampire movie, featured a bat-to-man transformation but depicted a devil rather than a vampire. Close, but no cigar. Other early films like The Vampire Dancer (1912) explored vampiric themes without depicting supernatural creatures.

F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (1922) stands as the first true cinematic vampire milestone. This unauthorized adaptation of Stoker’s Dracula faced immediate legal challenges from Stoker’s estate. The court ordered all copies destroyed. Like its vampiric subject, however, the film refused to stay dead.

Nosferatu: The Revolutionary Masterpiece

To circumvent copyright issues, the filmmakers altered character names. Count Dracula became Count Orlok. Mina became Ellen. Van Helsing was replaced by Dr. Bulwer. The title “nosferatu” was adopted from Gerard’s 1885 essay “Transylvanian Superstitions,” though the word’s exact origins remain unclear.

Nosferatu made several revolutionary contributions to vampire cinema and horror generally. Most significantly, it introduced the concept that sunlight could kill vampires. This detail was entirely absent from Stoker’s novel. Count Orlok dies when he becomes too preoccupied attacking Ellen to notice the rising sun. Its rays prove fatal. This single creative decision became virtually axiomatic in subsequent vampire films.

Revolutionary Contributions of Nosferatu

- Sunlight as vampire weakness: First film to make sunlight deadly to vampires

- Vampire as disease: Orlok brings plague rats, embodying contagion

- Expressionist visual style: Created atmospheric horror template

- Monstrous appearance: Rat-like features contrasted with later suave vampires

Max Schreck’s portrayal of Count Orlok established a distinctly monstrous visual approach. Orlok’s deformed appearance, rat-like teeth, and bat-like mannerisms created a creature of pure nightmare. This grotesque design emphasized the vampire as disease incarnate. Orlok brings plague rats to the town. He IS the contagion.

Murnau’s German Expressionist background influenced the film’s visual style. He created a cold, depressing world that used environment to convey emotional states. The soft-focus cinematography, achieved by filming through gauze, created a hallucinatory atmosphere. It visualized the blurring between reality and nightmare.

The film’s lasting impact extended through Werner Herzog’s 1979 remake, television productions like Salem’s Lot, and countless references in popular culture. Even SpongeBob SquarePants references Orlok. That’s cultural penetration.

Universal Monsters: Dracula (1931) and Gothic Cinema’s Birth

Dracula (1931): Defining the Icon

Universal Pictures’ Dracula, directed by Tod Browning and starring Bela Lugosi, fundamentally shaped public perception of vampires. Released just nine years after Nosferatu, this black-and-white production introduced Lugosi’s iconic portrayal. It became the definitive standard for the “generic vampire.” Every vampire since either follows or rebels against Lugosi’s template.

Lugosi’s performance imbued Dracula with sophisticated style that blurred the lines between man and monster. His Hungarian accent, sweeping gestures, widow’s peak hairstyle, star pendant, bowtie, and collared cape became instantly recognizable. These characteristics are widely mimicked across media even today. Lugosi initiated the trend of the attractive vampire. His allure stemmed from sophistication and Old World charm rather than mere physical beauty.

The film’s production reflected the economic realities of the Great Depression. Rather than adapting Stoker’s novel directly, the screenplay primarily drew from Hamilton Deane and John L. Balderston’s successful 1927 stage play. This decision was made to conserve time and money. Sometimes constraints breed creativity.

Lugosi’s Dracula: Defining Characteristics

- Hungarian accent and theatrical delivery

- Iconic cape and formal evening wear

- Sophisticated, aristocratic demeanor

- Hypnotic eyes and commanding presence

- “I vant to suck your blood” (though never actually said in the film)

Tod Browning’s direction emphasized atmosphere over action, utilizing his silent film background to create eerily quiet sequences. The deliberate lack of music in many scenes heightened tension. Audiences were accustomed to full soundtracks accompanying silent films. This minimalist approach created an unsettling auditory landscape that emphasized the supernatural’s intrusion into the mundane world.

A remarkable aspect of the production involved the concurrent filming of a Spanish-language version. The same sets were used but with different cast and crew. The Spanish team filmed at night after the English crew finished. They operated on a smaller budget while completing production in roughly half the time. By reviewing dailies from the English production, they refined their techniques. Many critics consider their version technically superior with more fluid cinematography.

Dracula‘s success launched Universal’s monster franchise and established conventions that became standard in vampire cinema. The film spawned sequels like Dracula’s Daughter (1936), which featured notable homoerotic undertones despite the restrictive Hays Code. Later came the monster rally films of the 1940s.

Universal’s Vampire Legacy

Dracula’s Daughter (1936) served as a direct sequel, immediately picking up after the first film’s conclusion. Gloria Holden’s Countess Marya Zaleska struggled against her vampiric nature while displaying clear attraction to women. The film’s psychological approach and sympathetic portrayal of the vampire predated later trends toward complex, morally ambiguous undead characters.

The series continued with Son of Dracula (1943), starring Lon Chaney Jr. Then came the monster rally phase with House of Frankenstein (1944) and House of Dracula (1945), both featuring John Carradine as the Count. These productions functioned as loose mash-ups. They connected Dracula to Universal’s broader monster universe while allowing for independent viewing.

The monster rally era culminated with Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948). Lugosi reprised his role as Dracula for the second and final time. While often blamed for the decline of Universal’s classic monster series, these films reflected the genre’s natural evolution. Post-war audiences increasingly preferred comedy over pure horror. Change was inevitable.

Hammer Horror Dracula Films: Gothic in Technicolor

The Technicolor Revolution

Hammer Film Productions revitalized horror cinema in the mid-20th century. They transformed the genre through their distinctive “English Gothic” approach. Their revolutionary contribution? Bringing Technicolor to horror for the first time. They created lavishly Gothic visual experiences that attracted A-list actors while forging a unique aesthetic.

Hammer’s winning formula emerged with The Quatermass Xperiment (1955). But their iconic monster features cemented their legacy. The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and Dracula (1958) became the gold standard. Dracula (released as Horror of Dracula in the United States), directed by Terence Fisher, embodied the quintessential Hammer ethos.

Christopher Lee’s Erotic Dracula

Christopher Lee’s portrayal redefined the vampire archetype completely. He introduced dark, brooding sexuality combined with regal presence and fierce intensity. Lee consciously presented Dracula as “heroic, erotic and romantic.” He believed previous portrayals had missed these essential aspects. His imposing physical presence created a vampire who was simultaneously attractive and terrifying.

Dracula (1958) introduced several iconic visual elements that became synonymous with vampire mythology:

Hammer’s Visual Innovations

- Pronounced fangs and red contact lenses

- Blood spattering over coffins in vivid Technicolor

- Lavish Gothic castle interiors with rich period detail

- Rich crimson and shadow color palette

- Violent, spectacular death scenes

Peter Cushing’s Professor Van Helsing established him as Dracula’s relentless pursuer. Their dynamic was often interpreted as a battle between “rationality versus rampant desire.” Their confrontations represented broader conflicts between civilization and primal nature. Good versus evil. Science versus superstition. Order versus chaos.

Hammer’s aesthetic featured “deliciously vibrant hues: deep velvets of red and enveloping shadows.” The studio’s innovative use of color, especially crimson reds against Gothic backdrops, breathed new life into supernatural horror. Blood had never looked so vivid. So seductive. So terrifying.

Unlike Universal’s Germanic castles, Hammer’s settings maintained unmistakably British character. Lavish period furnishings. Ornate Gothic architecture. Intimate drawing rooms where seduction and destruction unfolded in equal measure.

Expanding Hammer’s Vampire Universe

Hammer’s films were characterized by pronounced sensuality and overt sexuality. The vampire’s bite became a sexually charged act laden with terror and desire. This approach, combined with vivid gore by era standards, made Hammer’s productions both groundbreaking and controversial. They pushed boundaries. Censors pushed back.

The studio redefined the femme fatale through captivating women who were often sources of peril themselves. Ingrid Pitt’s roles in The Vampire Lovers (1970) and Countess Dracula (1971) showcased powerful, sexual female vampires. These weren’t victims. They were predators.

The Karnstein Trilogy, beginning with The Vampire Lovers, explored the lesbian vampire subgenre with increasing explicitness. Lust for a Vampire (1971) and Twins of Evil (1971) followed. These productions reflected changing social attitudes toward sexuality while maintaining Gothic horror’s atmospheric traditions.

Despite mixed initial critical reception—some called it “singularly repulsive”—Dracula (1958) achieved phenomenal international success. It turned Christopher Lee into a star and solidified Hammer’s reputation. The film is now recognized as a respected British classic. It offered significant social, cultural, and historical commentary on 1950s attitudes toward sex, violence, and women’s autonomy.

Blacula and Black Horror: Breaking Racial Barriers

Revolutionary Representation in Vampire Cinema

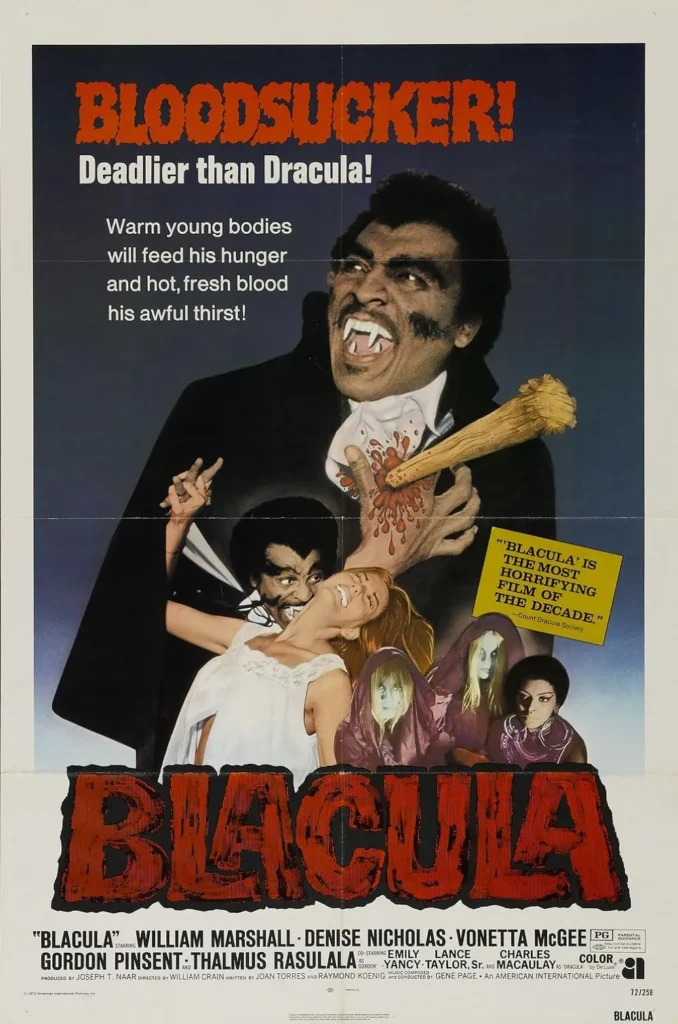

Blacula (1972), directed by William Crain, emerged as a pioneering entry in black horror during the blaxploitation film boom. This production transcended typical crime genre conventions. It ventured into horror to interrogate white racism while challenging monstrosity tropes. The title sounds exploitative. The execution was surprisingly sophisticated.

The film’s central narrative revolves around African Prince Mamuwalde, played with Shakespearean gravitas by William Marshall. He is cursed by Dracula and transformed into the titular vampire. After Dracula’s assault on Mamuwalde’s wife Luna, the prince suffers immortality alone for centuries. He awakens in 1970s Los Angeles. The modern world has little place for ancient royalty.

Upon his modern awakening, Mamuwalde embarks on a quest to find his reincarnated love. This introduced the “reincarnated love” trope that would influence later vampire cinema. This element transforms the vampire from mindless monster into “handsome, melancholic, and tortured monarch.” Love becomes the driving force. Not hunger. Not evil. Love.

Blacula’s Cultural Impact

- First major black vampire protagonist in cinema

- Introduced reincarnated love storyline to vampire mythology

- Critiqued white power structures through horror metaphor

- Influenced later vampire romances and tragic narratives

- Spawned sequel Scream Blacula Scream (1973)

William Marshall brought dignity and gravitas to the role. His Shakespearean training showed. This wasn’t a caricature or stereotype. This was a complex character struggling with curse, loss, and displacement. Marshall refused to let the material descend into mere exploitation.

Despite progressive elements, Blacula struggled with certain stereotypical portrayals. The film notably avoided turning white victims into vampires, instead choosing to kill them. This highlighted its racialized approach to vampirism while creating complex commentary on power dynamics and representation in horror.

The movie proved that black audiences hungered for horror representation. It also demonstrated that compelling storytelling could emerge from exploitation frameworks. Blacula opened doors for future black horror while establishing vampires as viable vehicles for social commentary.

The 1990s Revival: Romantic Vampires Ascendant

Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992): Gothic Maximalism

Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula marked a crucial turning point in vampire cinema. It combined lavish period production with modern filmmaking techniques. The budget was massive. The ambition was even larger.

The film emphasized the reincarnated love storyline, with Gary Oldman’s Dracula driven by centuries-old grief. His lost wife Elisabeta is reincarnated as Mina Harker (Winona Ryder). This transforms Dracula from monster into tragic romantic hero. Love conquers death. Love conquers evil. Love conquers all.

Coppola’s approach prioritized visual spectacle and romantic tragedy over pure horror. The film’s Academy Award-winning costume design and innovative practical effects created a sumptuous Gothic world. It influenced vampire aesthetics for decades. Oldman’s shape-shifting Dracula ranged from elderly nobleman to wolf-like beast to romantic lover. This showcased the character’s multifaceted nature.

The film’s emphasis on tragic romance rather than supernatural horror signaled vampire cinema’s shift. Vampires became sympathetic monsters worthy of audience empathy rather than pure fear. This would define the next three decades of vampire media.

Anne Rice and the Rise of the Romantic Vampire

Neil Jordan’s Interview with the Vampire (1994) brought Anne Rice’s influential novels to mainstream audiences. It fundamentally altered vampire cinema’s emotional landscape. The film starred Tom Cruise as the vampire Lestat and Brad Pitt as Louis. Their relationship explored immortal existence’s psychological toll through Gothic melodrama.

Rice’s vampires sought moral redemption, knowledge of their origins, and companionship in their immortality. This departure from traditional monsters infused vampires with complex emotional lives. They became tragic figures worthy of sympathy rather than destruction. The monster had become the hero.

Anne Rice’s Vampire Innovations

- Vampires as tragic heroes seeking redemption

- Complex vampire society and mythology

- Homoerotic undertones and chosen family themes

- Immortality as curse rather than blessing

- Beautiful, sophisticated vampire aesthetics

The film’s success established vampires as viable romantic leads. It paved the way for later productions that emphasized emotional complexity over pure horror. Rice’s influence extended beyond cinema into television, literature, and popular culture. Vampires became acceptable protagonists rather than antagonists.

The homoerotic subtext between Louis and Lestat was groundbreaking for mainstream cinema. Their relationship functioned as surrogate for gay partnerships at a time when such representation was rare. Vampires provided safe metaphorical space for exploring queer themes.

From Dusk Till Dawn (1996): Genre-Bending Violence

Robert Rodriguez’s From Dusk Till Dawn, written by Quentin Tarantino, exemplified 1990s vampire cinema’s willingness to experiment with genre conventions. The film’s first half functioned as crime thriller. Then it explosively transformed into supernatural horror during its second act. Nobody saw it coming.

The movie’s vampires returned to monstrous roots. They featured grotesque transformations and animalistic behavior that contrasted sharply with the decade’s romantic trend. These weren’t brooding aristocrats. They were monsters. Pure and simple.

This dual approach—combining crime genre elements with traditional vampire horror—demonstrated the archetype’s continued versatility. Vampires could be romantic heroes. They could be action protagonists. They could be pure monsters. The mythology was flexible enough to support any narrative approach.

Modern Vampire Movies and TV: The Sympathetic Era

Television’s Golden Age: Buffy and True Blood

Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) revolutionized vampire media. It used supernatural elements as metaphors for adolescent experiences. High school became a literal hellmouth. Everyday teenage struggles manifested as supernatural threats.

The series introduced complex vampire characters like Angel and Spike. They evolved from antagonists to romantic interests to eventual heroes. This character development was unprecedented. Vampires had never been so thoroughly humanized.

Buffy’s Vampire Innovations

- Vampires as metaphors for real-world teenage issues

- Long-form character development across multiple seasons

- Complex moral ambiguity between good and evil vampires

- Integration of vampire lore with contemporary settings

- Exploration of vampire redemption and soul concepts

Alan Ball’s True Blood (2008-2014) brought vampire sexuality and politics into the HBO era. The series used vampire “coming out” as allegory for LGBTQ+ rights. It explored themes of religious fundamentalism, racism, and political corruption in the American South. The show’s explicit content and complex mythology expanded television vampire storytelling’s possibilities.

True Blood presented vampires as marginalized minority seeking civil rights. They wanted to integrate into human society. This approach reflected contemporary social justice movements while maintaining supernatural entertainment value.

Action-Horror Revolution: Blade and Underworld

Blade (1998) revolutionized vampire cinema by successfully blending action and horror. Wesley Snipes’ “daywalker” character possessed vampires’ strengths without their traditional weaknesses. He created a new template for vampire action heroes. Vampires could be protagonists in action films.

The film’s success demonstrated that R-rated vampire content could achieve mainstream commercial success. Blade proved that vampires didn’t need to be romantic or sympathetic to work in modern cinema. Sometimes they just needed to kick ass.

Blade’s Impact on Vampire Cinema

- Introduced vampire-human hybrid protagonist

- Demonstrated viability of R-rated vampire action

- Influenced Marvel’s future film strategies

- Created template for supernatural action heroes

- Spawned successful franchise with two sequels

The Underworld franchise (2003-2016) expanded this approach through elaborate vampire-werewolf war mythology. Kate Beckinsale’s vampire warrior Selene wore leather and wielded modern weapons. These films emphasized supernatural action over horror. They created leather-clad vampire warriors equipped with contemporary technology.

Both franchises demonstrated vampire cinema’s capacity for reinvention. They maintained core supernatural elements while adapting to new genre expectations. Vampires could be action heroes, romantic leads, or traditional monsters depending on storytelling needs.

International Perspectives: Let the Right One In

Tomas Alfredson’s Swedish film Let the Right One In (2008) offered a contemplative, art-house approach to vampire cinema. It emphasized character development over genre conventions. The relationship between 12-year-old Oskar and vampire child Eli created haunting commentary on loneliness, bullying, and childhood innocence.

The film’s minimalist approach and snowy Swedish setting created atmospheric horror. It relied on suggestion rather than explicit violence. The vampire’s hunger became secondary to the characters’ emotional connection. This proved that vampire stories could succeed through subtlety and restraint.

Its critical acclaim demonstrated continued appetite for sophisticated vampire cinema. International perspectives brought fresh approaches to familiar mythology. Vampires weren’t exclusively American or British property anymore.

Contemporary Variations: Romance, Comedy, and Subversion

The Twilight Effect: Redefining Vampire Romance

Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight saga represents vampire cinema’s most commercially successful reinvention. It fundamentally altered vampire mythology for younger audiences. The series shifted genre focus from horror to romance. It introduced radical departures from established vampire lore.

Meyer’s vampires sparkled in sunlight rather than burning. They possessed superhuman beauty and strength. They formed monogamous family units. Edward Cullen’s vegetarian lifestyle—feeding on animal rather than human blood—created a “safe” vampire suitable for teenage romance.

Twilight’s Controversial Changes

- Sparkling skin instead of sunlight vulnerability

- Vampires with reflections and photographs

- Vegetarian vampires avoiding human blood

- Emphasis on abstinence and traditional values

- Removal of traditional vampire weaknesses

The series faced criticism for romanticizing potentially abusive relationship dynamics. It removed vampires’ essential danger. However, its massive commercial success—over $3.3 billion worldwide—demonstrated vampire stories’ continued commercial viability. It introduced vampire mythology to new global audiences.

Twilight proved that vampire stories could succeed without horror elements. Romance alone could sustain entire franchises. This insight influenced subsequent vampire media across multiple platforms.

Horror-Comedy Perfection: What We Do in the Shadows

Taika Waititi and Jemaine Clement’s What We Do in the Shadows (2014) achieved horror-comedy perfection. The mockumentary format satirized vampire tropes while maintaining genuine affection for the genre. The film followed centuries-old vampires sharing a flat in modern Wellington, New Zealand.

The production’s humor derived from ancient beings struggling with contemporary mundane concerns. Household chores. Paying rent. Nightclub door policies. This approach made vampires relatable while cleverly subverting traditional horror expectations.

Why What We Do in the Shadows Works

- Mockumentary format allows natural comedy timing

- Respectful parody that loves the source material

- Perfect cast chemistry and improvisation skills

- Genuine monster movie atmosphere maintained

- Successful transition to acclaimed television series

The film’s success spawned a television adaptation that expanded the concept. It maintained the original’s clever balance between comedy and supernatural elements. The show proved that vampire comedy could sustain long-form storytelling.

This approach influenced other vampire comedies and demonstrated the mythology’s flexibility. Vampires could be scary. They could be romantic. They could be absolutely hilarious.

Netflix Era and Streaming Innovation

Modern streaming platforms have created new opportunities for vampire content. Netflix’s animated Castlevania series brought video game vampires to streaming audiences. Mike Flanagan’s Midnight Mass reimagined vampire mythology through religious horror. These productions demonstrate continued innovation in vampire storytelling.

Contemporary vampire media increasingly emphasizes diversity. Complex mythology. Genre-blending approaches that appeal to global audiences while respecting genre traditions. Streaming platforms’ global reach creates opportunities for vampire stories from diverse cultural perspectives.

The future promises vampire stories from non-Western perspectives. These may introduce new mythological elements while respecting established traditions. The vampire’s remarkable capacity for reinvention suggests continued evolution ahead.

Thematic Analysis: What Vampires Really Represent

Disease and Contagion: The Eternal Fear

From folklore origins to modern cinema, vampires have symbolized humanity’s fear of disease and contagion. Original Slavic vampires were blamed for village illnesses. Modern vampire media often frames vampirism as viral infection or addiction requiring medical intervention.

Films like 28 Days Later and recent zombie media have adopted vampire-like contagion themes. Productions like The Strain explicitly connect vampirism to parasitic infection. This enduring metaphor reflects persistent anxieties about invisible threats and loss of bodily autonomy.

The COVID-19 pandemic gave new relevance to vampire contagion themes. Vampirism’s viral transmission parallels real-world disease fears. The bite that transforms reflects anxieties about contamination and loss of self.

Sexuality and Forbidden Desire: The Bite as Metaphor

Vampires have consistently served as metaphors for transgressive sexuality. From Carmilla‘s lesbian undertones to The Hunger‘s explicit queer desire, the vampire’s bite functions as sexual metaphor. It’s intimate. Penetrative. Transformative. It allows exploration of taboo subjects through supernatural displacement.

Modern vampire media continues this tradition through diverse representation and complex relationship dynamics. They challenge traditional sexual norms while maintaining supernatural allure. The vampire remains cinema’s most sexually charged monster.

The bite itself symbolizes forbidden desire and loss of control. It represents surrendering to primal instincts that civilization attempts to suppress. This makes vampire stories inherently erotic regardless of their surface content.

Immigration and Xenophobia: The Foreign Threat

Count Dracula’s role as foreign invader threatening British society reflects persistent anxieties about immigration and cultural change. Nosferatu‘s rat-like Orlok embodied anti-Semitic stereotypes while representing fears of Eastern European influence.

Contemporary vampire media often subverts these themes. It positions vampires as marginalized minorities seeking acceptance rather than foreign threats. This reflects changing attitudes toward diversity and inclusion. The monster becomes the victim seeking understanding.

This evolution demonstrates how vampire stories adapt to contemporary social attitudes. They can reinforce xenophobic fears or challenge them depending on creative choices and cultural context.

Class and Aristocracy: Power and Privilege

The evolution from peasant revenants to aristocratic predators reflects changing social anxieties about power and privilege. Modern vampire media frequently examines wealth inequality through immortal characters who accumulate resources across centuries.

Films like Only Lovers Left Alive explore how immortal beings relate to contemporary capitalism and consumer culture. Series like True Blood examine economic exploitation through supernatural metaphors. Vampires embody concerns about inherited wealth and systemic inequality.

The aristocratic vampire represents fear of elites who prey on common people. This metaphor remains relevant in eras of growing wealth inequality and corporate power concentration.

Mortality and Immortality: The Ultimate Desire and Curse

Vampire stories fundamentally explore humanity’s relationship with death and the desire for eternal life. While immortality initially appears desirable, vampire narratives typically reveal its psychological costs. Endless grief. Isolation. Moral corruption.

Modern vampire media increasingly emphasizes immortality’s emotional toll rather than its physical benefits. They create sympathetic characters struggling with eternal existence rather than reveling in supernatural power. Death becomes release rather than defeat.

This reflects contemporary anxieties about aging, medical technology, and life extension. If science could grant immortality, would we want it? Vampire stories suggest the answer might be more complicated than expected.

Frequently Asked Questions About Vampire Horror Movies

What was the first vampire horror movie?

F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (1922) is widely considered the first true vampire horror movie. While earlier films like George Méliès’ The Devil’s Castle (1896) featured bat-to-man transformations, they depicted devils rather than vampires. Nosferatu was the first feature-length film to portray a supernatural vampire as the central character, establishing many visual and narrative conventions that continue to influence vampire cinema today.

Why do vampires symbolize sexuality in horror movies?

Vampires symbolize sexuality because the act of feeding—the bite—functions as a sexual metaphor. The vampire’s bite is intimate, penetrative, and transformative, mirroring sexual encounters. This symbolism allowed filmmakers, particularly during censorship eras like the Hays Code, to explore forbidden desires and taboo sexuality through supernatural displacement. The vampire’s seductive power and the victim’s surrender to their bite represent the tension between civilized behavior and primal desires.

How did vampire movies change from horror to romance?

The transformation began with Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire novels in the 1970s, which portrayed vampires as tragic, sympathetic figures seeking redemption rather than purely evil monsters. This literary influence reached cinema through films like Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992) and Interview with the Vampire (1994), which emphasized romantic tragedy over pure horror. The trend culminated with Twilight (2008-2012), which completely removed horror elements in favor of teenage romance, sparkling vampires, and “vegetarian” lifestyles.

What makes Hammer Horror’s Dracula films special?

Hammer Films revolutionized vampire cinema by introducing Technicolor to horror in the 1950s-1970s. Their Dracula films featured vivid blood reds, Gothic castle interiors, and Christopher Lee’s intensely sexual portrayal of the Count. Unlike earlier black-and-white vampires, Hammer’s approach emphasized the seductive and aristocratic aspects of vampirism while maintaining genuine horror elements. Their lavish production values and adult themes influenced vampire aesthetics for decades.

Why are modern vampire movies so different from classic ones?

Modern vampire movies reflect contemporary social attitudes and filmmaking technologies. Where classic vampires were pure monsters representing foreign threats or disease, modern vampires often function as marginalized minorities seeking acceptance or tragic anti-heroes struggling with immortality. Contemporary vampire media addresses current issues like LGBTQ+ rights (True Blood), teenage romance (Twilight), urban action (Blade), and social comedy (What We Do in the Shadows). The basic vampire mythology remains flexible enough to support these diverse interpretations.

What’s the difference between Universal and Hammer vampire movies?

Universal’s vampire movies (1930s-1940s) were black-and-white Gothic productions emphasizing atmospheric horror and theatrical performances, particularly Bela Lugosi’s iconic Dracula. Hammer’s vampire films (1950s-1970s) introduced Technicolor, explicit sexuality, vivid gore, and Christopher Lee’s physically imposing, erotically charged Count. Universal focused on psychological horror and classic monster movie atmosphere, while Hammer emphasized visual spectacle, adult themes, and the vampire’s seductive power.

How did Blacula change vampire cinema?

Blacula (1972) was the first major vampire film to feature a Black protagonist and address racial themes within horror. It introduced the “reincarnated love” storyline that would influence later vampire romances, transforming the vampire from mindless monster into a tragic figure driven by lost love. The film also critiqued white power structures while providing representation for Black audiences in horror cinema, proving that vampire stories could successfully incorporate social commentary and diverse perspectives.

Why do vampire movies remain popular today?

Vampire movies remain popular because the vampire archetype is infinitely adaptable to contemporary fears and desires. Vampires can represent disease and contagion (relevant during pandemics), forbidden sexuality (evolving with changing social attitudes), class warfare (reflecting economic inequality), or immigration anxieties (adapting to current political climates). Their fundamental appeal—the promise of immortality and power combined with the curse of eternal existence—addresses universal human concerns about mortality, desire, and the price of transcending human limitations.

What are the best vampire horror movies for beginners?

For newcomers to vampire cinema, start with these essential films that showcase different eras and approaches:

- Classic Era: Nosferatu (1922) and Universal’s Dracula (1931)

- Technicolor Gothic: Hammer’s Horror of Dracula (1958)

- Modern Sympathy: Interview with the Vampire (1994)

- Action Horror: Blade (1998)

- Art House: Let the Right One In (2008)

- Horror Comedy: What We Do in the Shadows (2014)

These films represent the major evolutionary stages of vampire cinema and provide a comprehensive foundation for understanding the genre’s development.

The Future of Vampire Horror: Trends and Predictions

Contemporary vampire cinema continues evolving through diverse international perspectives, streaming platform innovation, and genre-blending approaches that maintain supernatural core elements while exploring new thematic territory.

Current Trends in Vampire Media

- International productions from non-Western perspectives bringing fresh mythology

- Climate change and environmental metaphors reflecting contemporary anxieties

- Technology integration showing vampires adapting to digital age

- Diverse casting and inclusive storytelling expanding representation

- Genre hybridization with science fiction and thriller elements

Future vampire stories will likely continue adapting to contemporary anxieties while maintaining the archetype’s essential appeal. Whether exploring artificial intelligence, climate catastrophe, or social media culture, vampires’ adaptability ensures their continued relevance in horror cinema.

Streaming platforms’ global reach creates opportunities for vampire stories from diverse cultural perspectives. These may introduce new mythological elements while respecting genre traditions. The vampire’s remarkable capacity for reinvention suggests cinema’s most enduring monster will continue evolving to reflect each generation’s fears and desires.

Conclusion: The Undying Legacy

From Slavic folklore to streaming series, vampire horror movies have demonstrated remarkable staying power through their unique combination of terror and allure. Unlike other horror monsters that inspire pure fear, vampires occupy the complex emotional territory between desire and revulsion. They represent humanity’s relationship with mortality, sexuality, and power.

Their evolution from diseased revenants to romantic heroes reflects changing cultural attitudes while maintaining essential supernatural appeal. Whether depicted as monstrous predators, tragic anti-heroes, or action protagonists, vampires continue providing rich metaphorical material for exploring contemporary anxieties.

The vampire’s enduring success lies in their adaptability. They can embody any fear. Represent any marginalized group. Symbolize any social concern. All while retaining their essential supernatural nature. This flexibility ensures vampire horror movies will continue captivating audiences.

They rise from cinema’s crypt to sink their teeth into new generations of viewers. As long as humans grapple with mortality, sexuality, and power, vampires will remain cinema’s most versatile and enduring monsters. Forever adapting to reflect our deepest fears while offering the tantalizing promise of transcending human limitations.

Their legacy proves that some stories, like the undead themselves, refuse to stay buried.